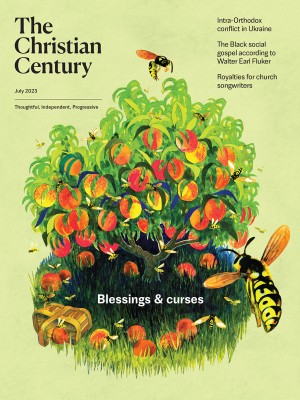

(Illustration by Julia Breckenreid)

My friend Joanne has been translating Deuteronomy word for word, a book she calls “the great poetic part of the Torah.” Joanne is 88 and the author of more than 20 novels. A former EMT, firefighter, and college professor, she is a master of English and a student of Hebrew. She and I meet monthly in a group of writers—a mix of Reconstructionist Jews and deconstructionist Episcopalians—and I suppose it shouldn’t surprise me that Deuteronomy would eventually come up. Everything else has. We’ve written letters to the dead. We’ve had extensive pretend correspondence with internet hucksters. One time we all wrote about knees. So why not Deuteronomy?

But I don’t think I had given Deuteronomy any thought since high school, when I was urged to read the Bible straight through as an act of pious stamina. By the time I got to Deuteronomy, I’m sure I was skimming and looking for the good parts. Until Joanne, I had never understood Deuteronomy as “the good parts.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

All of that changed in a glance at Deuteronomy 28: the blessings and the curses. I fell in love.

This chapter should not have compelled me. Biblical scholar Christopher Wright calls it “the most difficult chapter” of Deuteronomy for modern readers. The blessings last only 15 verses, but the curses rant for 52. On the surface, the chapter feels like a tiny carrot attached to a great big stick wielded by a God ready to rain blows on our heads at any moment: “The Lord will smite you with consumption and with fever and with inflammation and with fiery heat and with the sword and with blight and with mildew.”

This is in fact how fellow group member Marilyn read it. “This chapter is my father on steroids,” she said. Every imagined imperfection is punished. All love is conditional. “He would beat us if he thought our fingernails were too dirty,” she said. “This is the God I’ve been trying to escape all of my adult life.”

Wright writes that the blessings and the curses of Deuteronomy 28 were standard-issue for the ancient world. These were the kinds of things used in ordinary political documents to bind treaties: if you break your promises, here are the bad things that you can expect. They are almost something like a hex, writes Walter Brueggemann, a common recitation meant to create a binding. What is remarkable is not the words themselves, but the transformation of a political context into a theological one. This treaty is between God and the people—not between two battling tribes. “A self-conscious Israelite community,” Brueggemann proposes, “may have borrowed a covenant form deliberately to offer its covenant with YHWH as a radical alternative to alliance with Assyria.” This would make the document a defiant and rebellious one as well as one forged in a desire for obedience. It says yes to God while saying no to worldly forms of dominion.

The whole of Deuteronomy is a set of three songs or speeches of Moses before his death, and the blessings and the curses come at the end of the second song, as a way to seal the deal between God and the people. The book of Deuteronomy is fundamentally about boundaries: it is words spoken on the boundary between the wilderness and the promised land, between the past and the future, between the Torah and the prophets. Chapter 28 is a boundary within a boundary—standing on the edge between the second song of Moses and the third.

I began to feel drawn at verse 5. “Blessed be your basket and your kneading bowl.” Why, I wondered, start with the basket and the kneading bowl? What place does the bread basket have in intertribal hostilities or in a covenant between God and God’s people? I didn’t have an answer right away, but I was drawn to the image. I felt like I could smell the slight oiliness of the kneading bowl and feel its textures—a combination of rough and smooth. I could imagine the yeasty nature of the rising bread and feel the roughness of the handmade basket into which baked bread was laid. It was the essence of hearth. Home. The very place from which being human begins. Cooking, Michael Pollan argues, is how we became human. Humans took the elements of earth and added water and then fire. This alchemy was the beginning of the first human culture.

So if your blessings start with bread and the implements of bread, then you are very close to the essence of your civilization. The kneading bowl of Deuteronomy, as I imagine it, keeps a little of every loaf that ever came from it. The oils soak into the fired clay. The sticky dough clings to the sides. Every act of kneading, forming, and baking loaves is a blessing, and one that accumulates over time.

It makes sense to me then that this blessing is, in particular, a blessing for women. In what archaeologist Cynthia Shafer-Elliott calls the “gastro-politics” of ancient Israel, “the home was in the province of women, as was the spring and the bread oven.” Women prepared these loaves for their families, gave these loaves to their neighbors, spread these blessings across an entire people. Every aspect of this blessing involves human hands, most often female ones—not only the bread but also the kneading bowl and the basket themselves. These are foundational domestic arts.

“If we are going to survive,” I hear this part of Moses’ song saying, “we are going to need blessings on every aspect of our lives.” Such a blessing draws our attention to the mundane, to the basic work of survival within the human family. Daily actions and daily choices have consequences far beyond their seeming simplicity.

Obedience begins at the center of things. I hesitate to bring up the word obedience. I am taking some courage from Joanne here, who in our conversation about Deuteronomy 28 felt the need to mention, “I am pro-obedience, by the way.” So am I, I think, but not before noting the way that obedience has often been used in just the way Marilyn mentioned: blame, shame, censure—especially heaped upon women for all manner of failings. If the family doesn’t thrive, so goes the ancient formula, blame the woman at the hearth. Blame her kneading bowl and her basket. The God who is interested in the details of everyday life can just as easily be a petty tyrant as a loving creator, who punishes every small infraction and who would just as readily destroy a people as save one. There is no doubt that humans have very often used this image of God to control, abuse, and belittle one another.

But if we take the blame out of it for just an instant and imagine that this blessing was spoken through love and for the purpose of love, then we have the same words and images with a different inflection. “Our lives matter,” this blessing says, right down to their very details. This covenant that the people were making with God was not a covenant with a distant, foreign power. It was not about faraway things. This covenant enters into the most fundamental aspects of human existence and the rhythms of everyday life. It starts, as does so much of human life, in the kitchen.

But as with blessings so with curses. They start at the essence of things. Once the basket and the kneading bowl are cursed in verse 17, the curses proliferate.

I admit, I fell in love with the curses too, in part because they struck me as funny and tender. “He shall be the head and you shall be the tail,” reads one. “You shall not anoint yourself with the oil, for your olives will drop off.” Or perhaps my favorite: “You shall become a horror, a proverb, and taunt among the peoples.” Who knew that to become a proverb was a curse? What could be worse than becoming a proverb? Oh for the day when the Trumps become a proverb among the peoples! The more we read the curses out loud in our group, the more we laughed.

Joanne pointed out the relationship between these ancient curses and the way that cursing later developed in Yiddish-speaking culture. Pretty soon the Jewish part of the group was remembering Yiddish curses from their childhoods.

“May you be reincarnated as a chandelier so that you will hang all day and burn all night.”

“May your teeth fall out the day before Purim—except two that don’t meet.”

“May your daughter marry the Angel of Death and may a gentile come to tell you about it.”

Joanne pointed out that this is the language play of those without political or cultural power—those who of necessity wield the power of the word because the power of the sword is denied them. “They’re too elaborate,” Joanne says, “for plain rage. They are a celebration of weakness, not strength.” To her point, none of the Episcopalians could come up with comparable language play from our own childhoods or cultural contexts.

Not all of the curses are funny. Indeed it is the way that humor and horror lie side by side that provides some of the most compelling moments. Some of the curses felt all too familiar after multiple years of global pandemic, in the midst of climate change. Some of them seemed to find a precise language for what we have experienced: the plagues, the loneliness, the sorrow, the emptiness. Barren fields, the dust, the lack of rain, the storms and their consequences that seem greater than they used to be.

“And the heaven which is over your head shall be bronze and the earth which is under you iron. The LORD will make the rain of your land powder and dust; from heaven it shall come down on you until you are destroyed.” I thought of video footage I’ve seen of bombings and the aftermath of earthquakes, the dust-covered children pulled from rubble. I thought of the 9/11 first responders who emerged covered in dust that would later give them cancer. This unyielding heaven and unyielding earth did not feel foreign or faraway. I don’t know if I’ve ever encountered a better language for it.

Throughout this chapter runs a tension between collective responsibility and individual responsibility—the inner person and their relationship to the outer world. It is written in the future tense, as if the people are only at the very beginning of their relationship with God, when in fact this is a document coming from a later time, a time when the people sought to renew their covenant, not create it. They’ve already experienced plague, exile, loss, and destruction. It’s not theoretical.

Buried in those tensions we see a people grappling with the puzzle of existence. They’ve assigned meaning and consequences—if I/we do this, then that will follow—only to have those meanings and consequences pulled out from under them for no reason that they could ascertain. There is a direct line from Deuteronomy 28 to Ecclesiastes; it makes sense to wonder out loud why obedience and consequences are not related in the way we want them to be. “If what happens to the fool also happens to me,” asks the writer of Ecclesiastes, “then why have I been so very wise?” (2:15). Wisdom literature, as Clifford Geertz pointed out, teaches that the problem of suffering isn’t how to avoid suffering but how to suffer. How to make “physical pain, personal loss, worldly defeat, or the helpless contemplation of others’ agony something bearable, supportable—something, as we say, sufferable.”

The structure of Deuteronomy 28 is deceptively simple: obey the Lord, and the blessings will all be yours and the curses will all belong to somebody else. Yet the logic of cause and effect will not get us very far in interpreting this chapter. Everyone reading this, then as now, knew this wasn’t the case. If only “they” experienced bewilderment of heart and not “we.” If only they suffered devastation and we were always blessed with prosperity and good things and never suffered the “scab and the itch.”

Put into the whole context of the Jewish people, Susan Niditch says, we can understand blessings and curses theology as comments on and evaluations of society: How does a society treat its widows and orphans? How prevalent is violence, how much honesty can be anticipated, and is leadership fair or tyrannical? We might call this alignment as much as obedience. How aligned is our society to the will of God?

But chapter 28 also suggests that we can ask this question personally as well as socially: that we can bring these ancient blessings and curses very close to home through the question of alignment. This isn’t perhaps the reading we’ll find in every seminary classroom, maybe not what the scholars agree on as the fundamental meaning of the text, but as a contemporary reader of Deuteronomy, it continually surprised me with its availability.

What is the failure of the people that invited all of this destruction upon them? We often think of it, like Marilyn’s father, as a failure of obedience, a failure to adhere to the letter of the law—and the chapter certainly allows this reading. But there is a hint in the text that our failure has something to do with the question of how life is lived. Verse 47: “Because you did not serve the Lord your God with joy and a glad heart for the abundance of all things.” Is our life—both individually and communally—lived with joy and a glad heart? Does our “obedience” stem from a life-giving and life-receiving reciprocal relationship with our Creator?

With this in mind—that perhaps we fail at joy—we can return to the kneading bowl and the basket and wonder if we fail to appreciate the simple abundance of our lives, the most basic relationship to the earth and to other people. We don’t give thanks because we owe God our thanks; it isn’t another box to check. It’s because when we live in and through abundance, in alignment with the will of God, the goodness of God flows through us and out into all creation.

When we don’t live in joy and gratitude, when we become stingy and mean, the goodness of God becomes blocked and distorted—in us, through us. From the simple failure to heed joy comes deprivation—and deprivation spreads, the text exaggerates, until people are eating their own children’s flesh. The slavery from which you were delivered, the text says, will return to you along with all that came with it: the labor, the plagues, the suffering.

But once again, the end of the chapter holds a surprise. You would think that after eating your children and being destroyed by “every sickness and every plague,” the chapter would end with a landscape of collective despair. But it doesn’t. Instead it returns to an intimate place, the internal reality of the human being instead of the external one. “So your life shall hang in doubt before you, and you shall be in dread night and day, and you shall have no assurance of your life.”

Inside the mind and heart of the human being, Deuteronomy says, dread replaces joy. We are meant to live in joy. We are meant for joy. But dread becomes our companion. In the morning, you will wish it were evening. And in the evening, you will wish it were already morning. Anxiety replaces gratitude. The result of failing to live in relationship with God is ultimately an intimate one, aimed directly at the inner life of the human being, at her most secret thoughts and the most minute experiences of her days.

I don’t have to have eaten my own children or to have been at war with Assyria to know the experience described here. I know morning dread and evening dread. I know it can be caused by something as simple as a conversation I don’t want to have or the fact that I’ve indulged my anxiety to such a degree that I don’t want to stew all night in my own poisoned thoughts. This anxiety is rooted exactly in the place the text identifies it: lack of trust in God’s covenant with us, which is a little like saying the failure to delight in the ordinariness of days, of bread baskets and kneading bowls.