Were the lost gospels really lost?

The myth that alternative gospels were suppressed by empire and only recently rediscovered is too good to be true.

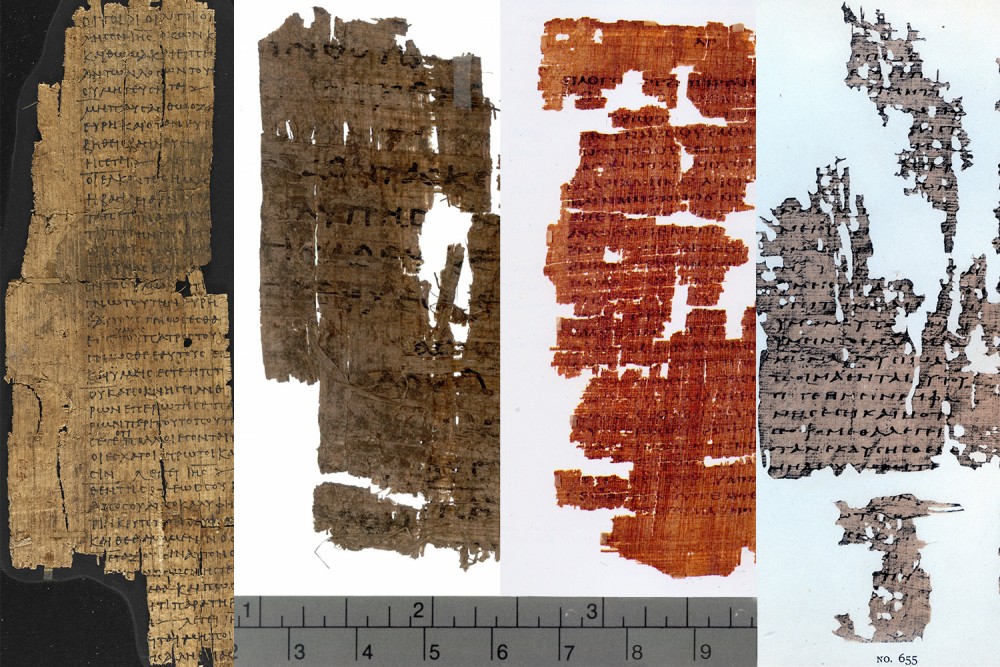

Papyri of various noncanonical gospels (Creative Commons)

Around 800, an unknown Irish monastery listed the appropriate liturgical readings for different feast days. For the mass of the circumcision, the text for the day came from the Gospel of James, presented with the words that would have been used to introduce a standard passage from canonical Mark or John. We have no idea where that church found such an out-of-the-way text, or what happened to it. Was the world’s last copy burned in a Viking raid?

In itself, such a mysterious story offers no fundamental revision of Christian history. But it does raise a question about a widespread and influential mythology concerning early Christianity, one that shows up every time someone claims to have found a lost ancient gospel. It is familiar to anyone who has read Dan Brown.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The story goes like this. In the earliest Christian centuries, a great many writings about Jesus circulated, and the number of claimed gospels might have run into the hundreds. As the Roman Empire made Christianity the state religion, so the number of acceptable gospels was rigidly pruned back, to our canonical Big Four, and those other embarrassing contenders were progressively suppressed. By the 380s, when imperial regimes decisively moved against the remaining gospels, one treasure trove was famously concealed at Nag Hammadi in Egypt. That hoard was rediscovered in 1945 and made widely available in translation in the 1970s, and only at that point were we at last able to glimpse the brilliantly diverse truths of the earliest Jesus movement. Finally, after 1,500 lost years, the truth was revealed.

It’s a classic story—a myth—of concealment and near-miraculous rediscovery, even a kind of resurrection, and if it seems too good to be true, that is just what it is. Most significantly, the great majority of those recently rediscovered texts were written at least a couple of centuries after Jesus’ time, and as such, they tell us nothing historically worthwhile about the apostolic age. In virtually every case, the authors took what they said about Jesus from one or more of the four canonical gospels and added their own particular theological bells and whistles.

But there are other problems. As that Irish story reminds us, alternative gospels did not actually vanish as neatly and suddenly as is claimed, nor was there any reason for them to. If the Roman Empire tried to suppress alternative gospels, this writ did not run beyond its frontiers, in the sprawling Persian Empire, or in intervening buffer states. Plenty of other gospels circulated freely in those areas, and for many centuries, and Christian dissidents regularly reimported them into the mainstream Catholic and Orthodox world.

Students of church history may know about heretical movements like the followers of Marcion and Bardaisan, which flourished in the second century. But most would be surprised to read Islamic writers of the 11th century who remarked on the gospels attributed to those ancient heretical leaders, which were still circulating freely across Central Asia and along the Silk Route. Christian numbers were very strong in these regions. This was also the territory of the far-flung Manichaean religion, which carried such esteemed early texts as the Gospel of Thomas wherever its followers traveled and evangelized: fragments appear in oases in China.

Islamic writers also had access to many early stories of Jesus that did not survive elsewhere, and some are evocative. They recall a provocative and mystical prophet who advises, for instance, “If people appoint you as their heads, be like tails” and “Be in the middle, but walk to the side.” These actually sound very much like the odd free-floating sayings of Jesus that appear in early Christian Fathers, the logia.

But even in the heart of Orthodox Christian Europe, alternative gospels continued to circulate, and some came close to canonical status. One of the earliest such works that we can realistically date is the Gospel of James, a protoevangelium or infancy gospel. Probably written in the 140s, it never went out of circulation, and it is the source for the vast majority of legendary tales about the Virgin Mary that through the centuries have formed the subject of tens of thousands of pious pieces of church art. This gospel is a primary influence on what we think we know about Christmas, and it had a powerful influence on the Qur’an.

A little later—from the fifth century?—is the Gospel of Nicodemus, which tells the story of Christ’s descent to hell after his crucifixion. That story likewise had a phenomenal impact on a millennium of Christian art, thought, culture, and liturgy. Had you asked an orthodox medieval Christian what were Jesus’ most famous words, the answer might well have been “Lift up your heads, O ye gates!” the war cry that he utters before storming hell to rescue the virtuous dead. Although the words are quoted from Psalm 24, the immediate source is the Gospel of Nicodemus.

These are just two examples of a great many alternative works that many churches read freely across Catholic and Orthodox Europe. Scarcely less influential were the very sizable bodies of Acts of various apostles, some of which included visions of Jesus rooted in Gnostic and heretical thought. One precious treasure of second-century Gnostic speculation is the stunningly evocative Hymn of the Pearl, which survives only because it was incorporated into the Acts of the apostle Thomas.

We also need to be very skeptical about claims that all those ancient visions of an alternative Jesus were lost until very modern times—indeed, until the 1970s. In fact, any educated person in 1900 had access to a substantial library of texts and translations that told you all you needed to know about the “Gnostic Jesus,” and new finds continued steadily throughout the early 20th century.

Once we admit this, however, we lose the romantic idea of the sudden revelation that burst upon us in our own time. Some myths are just too good to ruin with facts.