Patience is said to be a virtue. Said, at least, by parents to demanding children. But where does resigned passivity end and active patience begin?

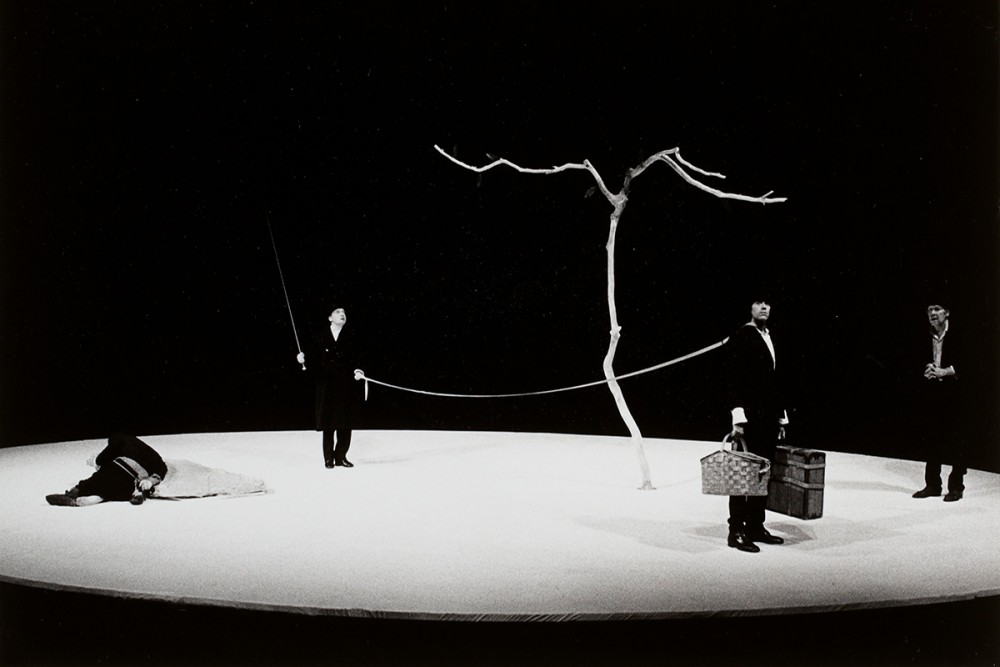

Samuel Beckett’s 1955 play Waiting for Godot offers a picture of two men, Vladimir and Estragon, displaying depressing inactivity. They remain stationary throughout the play. If you remove the last syllable of the title, you can read the story as a savage critique of Christianity. The two characters are ready for God to come and settle everything. Like members of a millennial sect, their existence is entirely focused on anticipating that God will appear. But their patience will never be rewarded: they’re waiting for someone who’s never coming and doesn’t exist.

Beckett is parodying not just Christianity but any search for meaning that assumes we’re on the verge of discovering our purpose in life. What drives you crazy when you’re watching the play is how passive Vladimir and Estragon are. Surely if Christ were coming, as traditional Christian conviction holds, he wouldn’t want us to idle our days in circular conversations and fruitless debate.