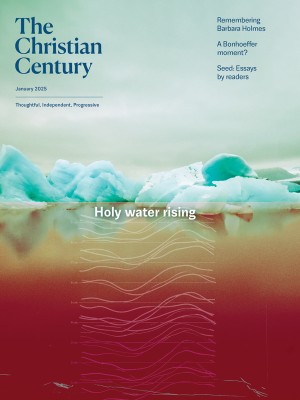

Sacred waters, melting ice

Baptismal rituals in glacial lands hold memories of the past—and wisdom for facing climate change.

Century illustration (Source image: Severin.stalder / Creative Commons)

All theology is contextual. The oldest law book in Iceland, Grágás, which emerged sometime between the ninth and 13th centuries, preserves an instruction for emergency baptism when traveling with a sick child. While fresh water is always preferable for baptism, Grágás instructs, it is also possible to baptize in the ocean or even in snow. The person who baptizes the child should draw three crosses in the snow and then address the water itself, saying, “I consecrate you, water.”

This Icelandic memory of baptizing in snow and salt water calls to mind the glaciers and sea ice that cover a good portion of the Arctic. They are the most stable form of water, and yet they are rapidly vanishing from our world—like the church ritual from Grágás. Amid the many environmental crises of our era, long-term climate change is causing glaciers to melt, from the Himalayas to the circumpolar regions.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Icelandic poet Andri Snær Magnason reflects on our relationship to the melting ice of the Arctic region in his 2019 book On Time and Water: “Glaciers are frozen manuscripts that tell stories just like tree circles and sedimentary deposits; from them, you can gather information and create a picture of the past.” When we read glacial texts as sites of cultural memory, he suggests, we can make meaning of both our past experiences and our present situation under climate change. But what does it mean to read a glacial manuscript? Magnason suggests that we need to “go backwards to move forwards,” which involves exploring the histories of human relationships to these giant icy bodies which human consumption is about to eliminate.

The vanishing glaciers, in Magnason’s view, are places to which we belong and relate as a species. Their melting has a particularly heavy impact on the Indigenous peoples who rely on semidomesticated animals, fisheries, and other livelihoods intricately linked to wildlife and climate, such as Inuits and Sámi reindeer herders. Fighting for the preservation of these sacred Arctic waters is a crucial part of the worldwide struggle, led by Indigenous people, to restore the earth.

Magnason’s metaphor of glacial manuscripts traces the interconnections between our textual histories and the landscapes that shape us as people of a particular place. If we follow his idea of connecting to our past to understand our future, how might this search for meaning shape our baptismal theology in the context of climate change?

As an Icelandic theologian, I approach this question by turning my gaze to the Arctic north, where Sámi and Inuit cultures are more visible than in other parts of Nordic countries. Thinking ecotheologically about baptismal practice in this context draws attention to the wounds of colonialism, revealing hard truths that demand a theological reckoning.

What might such a decolonization of baptism look like? Many theologians are beginning to realize that baptismal waters carry an ambiguous heritage. Coerced baptism and other similar missionary activities have often gone hand in hand with political, economic, and extractive abuses. Christian identity through baptism has come at a great cost, resulting in the loss of Indigenous land, autonomy, and culture. Many theologians are also becoming increasingly aware of the importance of learning from the wisdom, stories, and sustainable practices of Indigenous peoples.

Brazilian theologian Cláudio Carvalhaes argues in What’s Worship Got to Do with It? that “baptism is not only and solely a function of the church, not only the liturgy confirming the gospel, but a connected symbol to the sacred wisdom of the whole life of the community.” He describes visiting a small town in Mexico’s Sonoran Desert where the communal pool had three functions: “It was the water reservoir for the local community, gathering the rain that served for planting, cooking, and bathing; it was the baptismal font for baptisms; it was also the swimming pool for kids to have fun, and it was shared by the congregation.” This community’s practice embodies Carvalhaes’s vision of baptism as a communal manifestation of the imago Dei that disrupts structural sins and draws people together in new ways, uniting Christians in cosmic and sacramental relationship with the earth.

Glimmers of Carvalhaes’s vision of baptism emerge when we examine the baptismal practices of the early inhabitants of the glacial lands I now inhabit. Baptism outside of church buildings is still a widespread practice in both Iceland and northern Norway (in contrast to the other Nordic regions). This tradition has practical roots in the past: emergency baptisms were customary for Sámi nomads, and the pastor would later confirm the baptism when the parents brought the child to church. Lay baptism was—and still is—commonly practiced in northern Norway, especially among Laestadians, members of a pietistic revival movement that originated in 19th-century Sápmi. In Iceland, baptisms regularly take place in both homes and churches. In the summertime, they often take place outdoors, frequently in locations of historical importance to the baptismal families.

South Sámi theologian Bierna Bientie writes about the deep connections between baptism and his own geographic and cultural contexts. He describes the local waterways as part of eatneme (“Mother Earth” in the South Sámi language) and the springs as expressions of God’s generosity. He notes that Sámi baptismal practices focus on protection for the child, identity, and belonging more than on the traditional Lutheran doctrine of the forgiveness of sin. Water is central in Sámi baptismal practices, and it is common to use water from local sources with symbolic ties to the family. Bientie describes a Sámi baptismal liturgy that includes a prayer of thanksgiving for the water and the Holy Spirit. After the service, the water is poured out near the fireplace of the tent the child lives in.

The Nordic tradition of treating all water as holy because of Jesus’ baptism in the Jordan River is well documented, going as far back as the medieval era. A sermon for Epiphany appears in both the Old Icelandic Homily Book and the Old Norwegian Homily Book (both circa 1200). The Icelandic version succinctly states that Jesus asked to be baptized in the Jordan in order to hallow all water and all pools. This same idea of the universal sacredness of water appears in the story of Auður the Wise One in Landnáma, a 12th-century book about the Nordic settlement of Iceland in the ninth and tenth centuries. According to Landnáma, Auður instructed that her burial should take place down by the sea so that her grave would be daily cleansed by the water. Christianity was not an organized religion in Iceland at the time of Auður’s death, so there was no possibility for a burial in consecrated ground. But the sea was considered holy.

Icelandic baptism also has a historical connection to geothermal water. Iceland was Christianized around AD 1000, when representatives from across the land assembled and made the political decision that all of them would become Christian. However, those new baptismal candidates did not want to be baptized in the chilly waters of the parliamentary site, Þingvellir. Those who traveled south, north, and east after the parliament were baptized in the hot pools on their way home.

Like the community pool Carvalhaes observed in Mexico, which also served for washing and baptizing, the hot springs used for baptisms during the Christianization of Iceland are still considered to have healing powers. The same is true of baptismal water in general: elderly people still often wash their eyes in the water after a baptism. Like the South Sámi practice of respectfully pouring out the baptismal water near the fireplace of the family’s tent, there are accounts of Icelanders pouring baptismal water inside their houses for protection. As a young pastor in Westfjords, Iceland, at the turn of the century, I had parishioners who told stories of pouring baptismal water over the roof of their house as a blessing ritual. These days in Iceland, baptismal water is sometimes poured into the ground outside newly built houses.

Several Icelandic pastors have recently told me about their congregations’ baptismal practices that honor the holiness of the water. One pastor told the story of a family blending water from the parents’ two birthplaces into the font before a baptism, signifying a shared identity between the child and the parents. Many families bring water to baptisms from the Highland, the rugged wilderness area that is home to many of Iceland’s volcanoes, hot springs, and glaciers. Others ask their local pastor to join the family on a trip to the Highland to baptize.

The Nordic belief that Jesus’ baptism sanctifies all of the earth’s water prevents these practices from implying that a baptism’s efficacy relies on the particularities of the water used. All water is already holy, and any water can be used for baptism. We can even use snow or sea ice, as Grágás reminds us. At the same time, these rituals display the belief that the act of using water in a baptism changes it in some way. A person who pours baptismal water over the roof of their house to bless it wouldn’t do the same with regular tap water. It seems that something is happening to the water when a person says, “I consecrate you, water”—and perhaps also to our relationship with the water.

In a document written for the National Museum of Iceland called “Questionnaire: Admonitions and Beliefs,” retired pastor Vigfús Ingvar Ingvarsson recounts being asked to baptize a child close to a warm natural spring near a glacial river. It was one of two glacial rivers that were about to be dammed to create reservoirs for a power plant, which in turn would produce electricity for an aluminum factory. Ingvarsson tells the story this way (in my translation):

I baptized a child at Lindur, which is a warm spring that vanished in the Háls-lagoon when the dam at Kárahnjúkar was made. The baptism took place next to the spring and we took the water from it. It was deeply meaningful to the parents and the others who attended. This was on the 19th of August, 2006, and in addition to being a baptism, people experienced the ritual, I think, as the consecration of this land, where beautiful vegetation had been sentenced to go under the glacial water. They would also experience it as an acknowledgment or admonition that the land is sacred, and as a farewell ritual of this place.

The damming of the two glacial rivers took place only a few weeks after the baptism.

Our rituals carry a cultural memory that is connected to the history of water. If a glacier is a frozen manuscript, baptismal rituals in glacial lands hold wisdom about our past and our present. Reading the texts of our frozen waters may be instructive as we look to the future, especially if we let the practical wisdom of the land’s peripheral narratives, images, and practices take precedence over theory. The laws of Grágás prepared people for baptism in a state of emergency. With the earth rapidly warming, how might we interpret and practice the sacraments in the hour of our need?

As Ingvarsson shows in his account of baptizing in a place that was about to be sunk in water for industrial purposes, sacramental practices can function on many levels at once, including as environmental laments. Perhaps our baptismal theology should begin where Ingvarsson ends his story: with a consecration that is also an admonition and a lament. Such a theology might challenge us to say with dread and hope to all the earth’s endangered waters, “I consecrate you, water”—and then to ask for the courage to do something about it.

This essay is adapted from Guðmarsdóttir’s chapter in Baptism in Times of Change: Exploring New Patterns of Baptismal Theologies and Practices in Nordic Lutheran Churches (Church of Sweden Research Series), edited by Steinunn Arnþrúður Björnsdóttir, Magnus Evertsson, Harald Hegstad, Jonas Adelin Jørgensen, and Jyri Komulainen, forthcoming later this year from Pickwick. Used by permission of Wipf and Stock Publishers, wipfandstock.com.