An oracle of the word of the Lord?

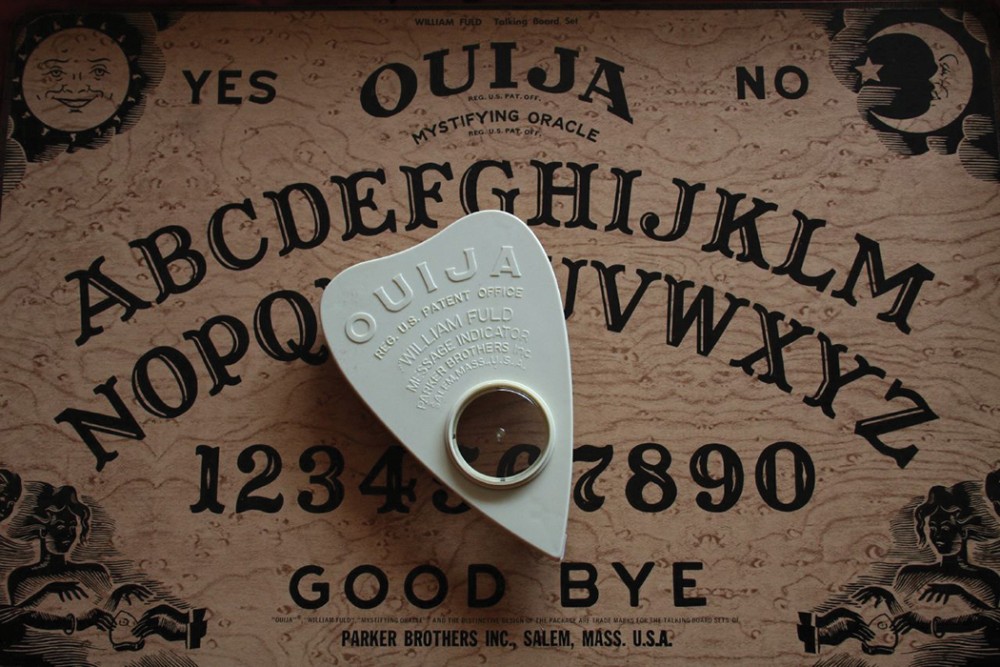

In the late 70s, two friends of mine housesat for the poet James Merrill—and got out his Ouija board.

There is a moment close to the center of Matthew, Mark, and Luke when Jesus asks his disciples to say who they think he is. It’s a strange question. By this point in their time together so much had already happened: miracles of every kind, sermons on the mountain and on the plain, conflicts with religious leaders, powerful demonstrations of spiritual authority, teaching. And yet after all this, as the disciples made their way toward yet another village in Caesarea Philippi, Jesus asks them not only what strangers think he is all about—how he’s doing in the polls—but what the disciples themselves make of him.

It’s all very well that some in the crowd think that he is John the Baptist come back from the dead, or Elijah, Jeremiah, or one of the other ancient prophets. But this isn’t what he’s after. Instead, he insists on going personal and, in the present tense, he asks, “But who do you say that I am?” (Matt. 16:15).

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

His point-blank question is, of course, meant to put them on the spot, to provoke an honest response. When Peter gives it—“You are the Messiah, the Son of the living God”—he offers the answer on which the church is built. But just as vital as the answer, I think, is the question itself, “But who do you say that I am?” It’s important that Jesus asks this not at the beginning of his relationship with the disciples but well down the road, and indeed not far from the end. It is as if to know who Jesus is means having to ask about him again and again; it means accepting the fact that you can never quite “get” him; it means acknowledging your need to know him for yourself and know him today.

And maybe it also means asking who he is outside of church, asking it anyplace where you find yourself in need or at a loss, anyplace where the answers are not already lined up and waiting for you to choose among them. It may mean that you need to step out of line, away from piety, and at a distance from all the received wisdom you have inherited.

What if, perhaps only for a moment, you let go of the bearded man in the stained-glass window. Let go of the “personal Lord and Savior” you could never quite got into your heart no matter how hard you tried. What if you put to the side, respectfully, the Second Person of the Blessed Trinity, Christ the King and Christ the Liberator, the one who “is named Wonderful, Counselor, Prince of Peace,” the Man of Sorrows, even (my favorite) Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s “Man for Others.” What if you risked asking, quite simply—and without being sure of the answer—“Who is Jesus Christ?”

Once upon a time I did. In the late 1970s I was at the beginning of my teaching career at Yale Divinity School and visiting friends who were housesitting in Stonington, Connecticut. Our absent host was the poet James Merrill, a friend of my friends, who was then in the process of writing what would become, by 1982, a three-part, 560-page epic poem, The Changing Light at Sandover. Crucial to its composition was a Ouija board that became the stage for sessions of serious play undertaken by Merrill and his partner David Jackson, not only on their own but often in the company of friends. (The board was given to Merrill by his best friend from high school, Frederick Buechner.)

Together Merrill and Jackson, plying the Ouija board with an inverted Blue Willow teacup, would contact spirits in an afterlife that may only have been their conjoined imagination. Night by night, and over the course of 40 years, they conjured a community of figures that included favorite poets, parents, deceased friends, and a host of other spirits who showed up on the board from . . . from where? Whatever one makes of its origins, the monumental poem that emerged from this is like nothing else in literature (although Dante’s Divine Comedy does come to mind).

Needless to say, the friends with whom I was visiting—both of whom were poets—took their housesitting as an opportunity to imitate the master: where was that Ouija board? For three days I watched the two of them sitting across from one another at Merrill’s dining room table. Each touched lightly the overturned teacup, whose handle served as a pointer to one place or another on the board. Taking turns, they asked their questions. In response, and to my utter incredulity, the cup shuttled purposefully, quickly, between vowels and consonants and the words yes and no. One of them took down the barrage of letters and symbols with his spare hand—a line of script that later would be divided into words and sentences. It all happened too fast for me to think that they were able to make it up on the spot. But what else could they be doing?

As young poets, my friends predictably brought questions to the Ouija board about the writers they loved (some of whom they managed to contact, or so it seemed). For my sake they asked about Dante, but without result. In his case, an afterlife door slammed shut: Dante was, as the board spelled out, “T O O H I G H.” I was stunned. If this was the unconscious taking over, it was definitely better than anything we had come up with in graduate school. But oddly enough, despite my literary training and passion for poetry, it was not really about literature that I wanted to know.

Throughout the weekend I watched them, dumbfounded, as an observer. By Sunday evening it finally got to be my turn. Didn’t I want, they asked, to try the board myself? Of course for three days I had been waiting for the invitation; but I was also fearful of what it would mean for me to put my fingers on the overturned teacup and then let go. Wouldn’t this be King Saul and the Witch of Endor all over again—a forbidden consorting with familiar spirits, a defilement with wizards and mediums? (We all know how that turned out for King Saul.) Besides, what if they ever heard about this at Yale Divinity School? Good-bye tenure.

Beginning to sweat, I sat myself down at the table, joined one of my friends at the board, put my hands on the Blue Willow cup, and shut my eyes. After a little while the cup began to move in slow circles, though without apparent direction from my friend and with absolutely no help from me. Then he said, “OK, Peter, what do you want to ask?”

To my embarrassment I found that despite three days of waiting for my chance, I had not actually formulated a question. I was there on the board, a teacup under my fingers, and nothing in mind. Until all of a sudden I realized that there was, in fact, only one thing I wanted to ask, a question I had never asked before, which was so deeply buried in me that I was astonished once I heard myself put it into words. It was as if in that moment I was discovering something about myself I didn’t know, some hunger. I opened my eyes and heard myself ask, “Who is Jesus Christ?”

The cup stopped tracing circles and then began to dart quickly (as if with a mind of its own) to the letters H, E, I, S, T, H—moving faster and faster until I could hardly keep up with it, but not so fast that the friend playing scribe could not copy down the letters and then decipher the message they formed. “Who is Jesus Christ?” I had asked. And the answer? “HE IS THE LENS IN THE DARK BOX.”

Can any good thing come off a Ouija board? Previously, I should not have thought so. The whole business was a parlor trick of another generation become, in the crazy 1970s, the pastime of poets who were out of my league. And yet, one Sunday night almost 40 years ago—with a teacup under my fingers and sweat pouring down my face—my natural skepticism, my Episcopalian rationality, my scriptural scruples, all met their match. I couldn’t dismiss what I had learned there about myself, let alone about Jesus Christ, as either the work of demons or mere “hoodoo voodoo.” Rather, I was taken someplace where I wouldn’t otherwise have gone on my own. I was blindsided by the Holy Spirit.

Not that I should have been entirely surprised by the weirdness of the context, for isn’t the Word of the Lord invariably spoken in impossible situations and inappropriate places: to an ancient couple with an old woman’s barren womb, in a death valley crowded with bones that are very dry, to a girl from a nowhere like Nazareth, at a public execution? Is anything too absurd or too embarrassing for the Lord?

Or is anything too metaphorical? Are any of Jesus’ names other than mysteries spelled out in letters, concealed in syllables and symbols? John the Baptist wonders if he is the “one who is to come.” Peter confesses him in one Gospel to be the Messiah, in another to be the Holy One of God. For others he was Master, Rabbi, Son of David, Son of Man, Son of God, King of the Jews— “the lily of the valley, the bright and morning star, the fairest of ten thousand.” And what did he call himself (with echoes of the divine “I am that I am” [Exod. 3:14])? “I am the bread that comes down from heaven,” “I am the light of the world,” “I am the way, the truth, and the life.”

But for me, having asked “Who is Jesus Christ?” in a highly improbable setting, he is first and foremost the lens in the dark box. He is the imaginable focus who enables me to conjure an unimaginable God. He is the human prism in whom a transcendent divine light becomes a set of shoulders overturning a table of money changers, a finger writing in the dust, a back being scourged, a voice in extremis crying out the words of a psalm. He is an aperture, an opening up of a darkness I cannot fathom. He is at once God’s question and God’s answer. He is the lens in the dark box.

A version of this article appears in the June 7 print edition under the title “Conjuring God.”