The real story behind ‘Good King Wenceslas’

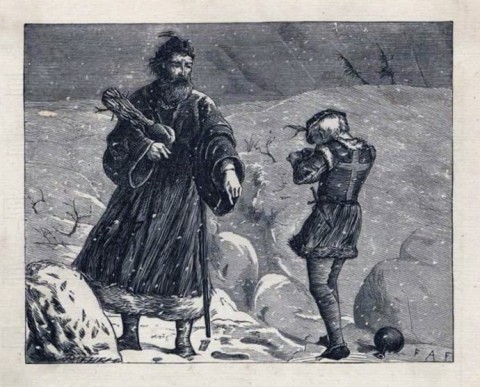

An engraving by Brothers Dalziel in an 1879 hymn book depicts the saint performing the charitable acts for which he became famous. (Image used in Creative Commons license)

Think of it as the English-speaking world’s most popular day-after-Christmas carol.

“Good King Wenceslas,” the British carol about a generous ruler trudging out in the snow to help a man on December 26—the Feast of Stephen—first appeared in a Victorian-era collection of children’s stories, with the intent of encouraging Christian charity.

But the inspiration for this fanciful tale was a very real Christian martyr who lived in the 10th century. The historical Wenceslas wasn’t English. He wasn’t a king. In his Czech homeland, he wasn’t even associated with Christmas.

However, he remains an important national figure in today’s Czech Republic—where he is known to Czech speakers as Václav rather than Wenceslas, the Latinized version of his name. The Catholic Church has named him the country’s patron saint. And he is meaningful to other Czechs as well.

“Václav is a prominent figure from our past,” said Jana Křížová, a United Methodist pastor in Prague. “He is a symbol of the Czech state.”

It also makes a certain poetic sense that a song about the Wenceslas of yore would be set on the feast day of Stephen, the first Christian martyr named in the New Testament.

Václav the Good lived from about AD 907 to 929. His father, Vratislaus I, was the Duke of Bohemia and a Christian. His mother, Drahomíra, though baptized before the marriage, was aligned with Bohemia’s pagans. As a child, Václav was raised largely by his Christian paternal grandmother, Ludmila—who was later canonized as a saint in her own right.

When Václav was about 13, his father died in battle and Ludmila became regent. But the regency did not last long. His mother had Ludmila killed—resenting her mother-in-law’s influence on the government and her soon-to-be duke son. Newly empowered, Drahomíra also sought to suppress Bohemia’s Christians.

When Václav became Duke of Bohemia himself at age 18, he instead sought to spread Christianity. He commissioned the building of several churches including part of what is now St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague. He also developed a reputation as a wise and compassionate ruler, known for his deeds of mercy.

Legend has it that he paid particular attention to caring for widows, orphans, and prisoners. He opposed the slave market and would buy enslaved people in order to set them free. He also is known for successfully negotiating peace with the Bavarians, who had been traditional enemies of Bohemians.

But his jealous younger brother, Boleslav, wanted to become duke himself and had the backing of their mother. Boleslav also was willing to exploit his brother’s faith to seize power. He invited Václav to a church dedication on September 27, 929. The next day, while Václav was on his way to prayer, Boleslav and his henchman attacked—killing the young duke.

Soon after his death, Václav’s tomb at St. Vitus became a popular site for pilgrimage, and through many shifts in what powers ruled the region, he remained a hero to the Czech people. To this day, he is still a familiar sight to many Czechs.

For nearly 100 years, a large statue of him as an armed knight on horseback has stood proudly in Prague’s Wenceslas Square. Václav’s feast day of September 28 is also a national holiday that celebrates Czech statehood.

Křížová, the United Methodist pastor, said most Czech people know few details of Václav’s life and they enjoy September 28 more as a day off than anything else.

Nevertheless, she said, whenever something significant happens in the life of the country, the Czech people crowd into Wenceslas Square.

On October 28, 1918, the Czech people gathered in front of the statue to hear the Czechoslovak declaration of independence. The square also was the main site of the Velvet Revolution, popular demonstrations in 1989 that nonviolently led to Czechoslovakia’s transition from Communist rule to democracy.

The transition of Václav, the saintly duke of Bohemia, to Wenceslas, the good king of Christmas-carol fame, came about 900 years after his reign. The song’s fans can thank John Mason Neale—a 19th century Anglican priest, scholar, and hymn writer—for this addition to the holiday season.

Neale spent much of his ministry translating devotionals and poems from Latin and Greek to make them accessible to English-speaking worshippers. Neale contributed other beloved hymns to the Advent and Christmas seasons including his translations and settings for “O Come, O Come Emmanuel” and “Good Christian Friends, Rejoice.” He also wrote some 60 hymns himself.

“Good King Wenceslas” first appeared in Neale’s Deeds of Faith, a children’s book from 1849, and again in his Carols for Christmastide from 1853. Neale set the words to the tune of “Tempus adest floridum,” (“Spring has now unwrapped the flowers”), a 16th-century song for spring.

In the carol, Wenceslas sees a man gathering winter fuel. Rather than ignoring the man and ignoring the need, Wenceslas goes bravely into the night through “rudewind’s wild lament and the bitter weather.” His page then follows in the good king’s footsteps, just as Christians are called to follow the path set by Christ.

In his native land, Křížová said the saintly ruler’s story continues to inspire.

“People still project their ideals onto the figure of Wenceslas,” she said. —United Methodist News Service