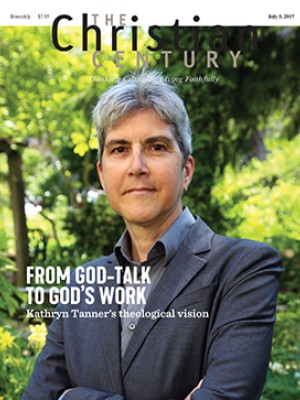

How Kathryn Tanner’s theology bridges doctrine and social action

Lots of theologians want to challenge economic injustice. Not many draw their arguments from Anselm and Aquinas.

"A Protestant anti-work ethic.” That’s how Kathryn Tanner characterizes the theme of the Gifford Lectures she delivered at the University of Edinburgh last spring, which will be published under the title Christianity and the New Spirit of Capitalism. This title recalls Max Weber’s famous argument about the connections between the Protestant work ethic and the rise of capitalism. However, Tanner comes to the opposite conclusion: the spirit of finance-dominated capitalism is inimical to Christian visions of human flourishing.

One feature of these lectures is a stunning reworking of the financial metaphors that have become a standard feature of Western theology. Traditionally, human sin has been portrayed as an unpayable debt to God, a failure to make good on God’s investment in us. We continually default on our obligation to please God, and indeed our sinful efforts in this regard only increase our debt. Since God is implacable in demanding full repayment and we are unable to do so, we must rely on Christ to repay what we owe to God.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Tanner undermines the assumptions of this economic framework for depicting God’s relationship to humanity. She shows instead how commitment to God—who sustains our life and works unstintingly for our good—interferes with a total investment in any human profit-making venture. For Christians, God takes on money’s character of putting every other good into perspective. In financial terms, money is the universal equivalent, the value that underlies that of every other commodity. For Christians, “God is the universal equivalent of all objects of value” in that their ultimate, underlying value is to enable all our pursuits to be turned toward God. In these lectures, Tanner takes familiar financial vocabulary and refashions it in a way that is genuinely good news for those crushed in the jaws of economic insecurity and injustice.

Capitalism is not an altogether new topic for Tanner. Her theological interest in confronting economic inequities was already evident in Economy of Grace (2005). But these recent lectures represent a culmination of Tanner’s theological work, bringing together the expansive theological vision she has spelled out in previous books with keen social and economic analysis of an urgent contemporary problem.

Sad to say, this kind of dynamic synthesis is not very common in contemporary theology. Tanner’s work bridges a common divide among her theological peers. She stands both with theologians whose work is oriented toward social action and with doctrinally focused theologians who tackle perennial issues in Christian theology, such as the relationship between nature and grace, the character of Christ’s atonement, and the working of the Holy Spirit. Tanner pursues central doctrinal issues in her books Jesus, Humanity, and the Trinity (2001) and Christ the Key (2010). At the same time, she is vitally concerned with theology as a practical discipline that offers guidance for human life. Whether the issue at hand is human sexuality or contemporary forms of capitalism, the task of the theologian, as Tanner sees it, is to bring the rich resources of Christian traditions to bear in creative and persuasive ways. In her own elegant fashion, Tanner is about the same task that preachers face every week: doing theology with the goal of shaping a way of life.

At a session on Tanner’s theology at a recent meeting of the American Academy of Religion (where scholars typically disperse into narrow interest groups) the panel of theologians engaging her work reflected her ability to bridge this common divide. It is hard to imagine another theologian whose work would attract commentators with interests ranging from “Christ’s Saving Death in Selected Greek Fathers” to “Antiracist Activism.”

One of the reasons Tanner’s ability to bridge different theological conversations is rare is that it requires so much reading. In addition to her wide knowledge of contemporary political and social theory, Tanner has the history of Christian theology at her fingertips. Her writing invites readers into conversation with an enormous range of Christian thinkers, from Cyril of Alexandria and Thomas Aquinas to Jürgen Moltmann and Janet Soskice. Her attention to early church theologians is especially distinctive: Athanasius, Gregory of Nyssa, Augustine, and others are regular conversation partners. For Tanner, figuring out in some detail what Christian faith is all about is an essential part of being a responsible Christian theologian, and that requires drinking deeply from the well of classical sources.

So what is Christian faith all about for Tanner? It is centered in Jesus Christ and develops around two main ideas: a noncompetitive understanding of God’s power and a stress on God as gift giver. We will explore these ideas one at a time.

For Tanner, divine and human agency are not in competition with each other. Because God is not in the same order of being as creatures, God’s agency operates on a different plane. God’s power, unlike the power of creatures, is universally extended beneficent power, immediately and intimately at work in all things. It is the kind of divine power Joseph speaks of when he says to his brothers, “Even though you intended to do harm to me, God intended it for good” (Gen. 50:20). God is at work on our behalf often in ways unbeknownst to us, or even contrary to our own intentions, yet without compromising our agency.

This noncompetitive view goes against the grain of a common Christian assumption that there is a zero-sum game between divine and human action—the more God acts, the less room there is for creatures to act. In this zero-sum understanding, God’s power needs to withdraw in order to make room for creaturely agency. God’s power needs to be a persuasive rather than coercive power, for example, or be otherwise checked in order to guard space for human freedom. God’s power, like creaturely power, is understood as external to other centers of agency, having to work from the outside to affect them.

Tanner rejects this view. Because God is the Creator of all, God’s agency is the ground of creaturely freedom and agency, not a threat to them. There is no incompatibility between “God’s universal, direct creative agency” and “the creature’s own power and efficacy.”

Another way this zero-sum understanding frequently appears is in assumptions about divine immanence and transcendence—the more God is transcendent of creation, the less God is immanent in it, and vice versa. According to Tanner, this approach also creates theological problems. When immanence receives too much emphasis, God stands as part of a single continuum of reality that embraces both creatures and Creator. When the stress is on transcendence, the temptation is to think of creatures as arranged in a hierarchy from those least like God to those most like God. This makes God’s relation to “lower” creaturely reality less immediate than God’s relation to the “higher” creatures.

Tanner refuses to see divine immanence and transcendence as a zero-sum game. The paradigm for her is Jesus Christ. The incarnation brings about the closest possible relation between the human being Jesus and God. In this union, neither the divinity of God nor the humanity of Jesus is compromised. Christ demonstrates God’s capacity to be in intimate relation with the world (immanence) without compromising God’s radical otherness (transcendence). Both fully immanent and fully transcendent to creation, God is neither to be opposed to creaturely reality nor identified with it.

A second central idea for Tanner is the notion of God as gift giver. As Creator, God is the giver of life, making all creatures totally dependent. This relation yields what Tanner calls a “weak” form of creaturely participation in God. But Tanner also makes gift giving central to her understanding of God’s redemptive work. Through Christ, God gives the world “God’s very own life and not simply some created version of it.” God saves us by establishing “the closest possible relationship with us.” This relationship happens through God’s Word taking on human flesh. Through this union, humanity is purified from sin, and given what, by nature, is beyond it: a “strong” participation in the life of God. The grace God gives us “is not ours by nature,” but in Christ by the power of the Spirit it becomes “naturally ours, or natural to us.” This gift of the goods of God’s own life is not something we have to earn or even consciously seek. Tanner can even say that in Christ we are “joined to God whether we like it or not.”

Tanner’s stress on the universal reach of God’s gifts through Christ and the Spirit renders the role of church uncertain in Tanner’s theology. What does salvation in Jesus Christ look like here and now? How important is our conscious participation in it? Tanner has not addressed these questions as explicitly as some of her readers would like. Still, her theology is attractive and persuasive to many because it revolves around an expansive vision of God’s ongoing work to overcome all that stands in the way of creaturely participation in the divine life.

Tanner has not always been so fearless in articulating her theological vision. In a 2010 Century essay (“Christian claims: How my mind has changed”), she reflected on her shift from a preoccupation with justifying the theological enterprise in general to an exploration of how Christian theology can address the most pressing human problems. In the years since that essay, the import of this shift has become clear.

Because of her concern for real-world engagement, Tanner has become wary of too much emphasis on theological method, which tends to lay down general rules instead of attending to concrete cases. According to Tanner, where a theologian ends up is more important than where she starts—and where she starts is no guarantee of where she will end up. Karl Barth and Paul Tillich, for example, with their very different theological approaches to revelation and human experience, both opposed National Socialism.

Attention to theological method was in vogue when I was in graduate school at Yale 30 years ago, when Yale and the University of Chicago represented competing approaches. Shifts in faculty and larger changes in the theological field have made this contrast less sharp than it once was. Yet Tanner remains unusual in that she has divided her career between both places. She studied at Yale, taught there for a few years, then spent 15 years teaching at Chicago before returning to Yale in 2010 as professor of systematic theology. In her work at both institutions, she has joined a wide variety of contemporary theologians who engage the social sciences.

Tanner’s contribution to the conversation between theology and the social sciences is spelled out in her 1997 book, Theories of Culture. While retaining the ecumenical spirit of her teacher George Lindbeck, she responds to his widely discussed book The Nature of Doctrine by insisting that cultures are never self-contained, consistent wholes. A group’s cultural identity is always in motion, forged in complex relation with others. This means that Christian attempts to delineate a clear and unchanging set of practices and beliefs in order to establish a definite social boundary between the church and the world are misguided. A Christian way of life is always parasitic on other ways of life. Christian practices, Tanner insists, are “always the practices of others made odd.” Testing the spirits of the larger culture (1 John 4) is an ongoing task for communities of Christian faith. The relationship between Christ and culture, to recall H. Richard Niebuhr’s famous title, always has to be worked out piecemeal.

This means for Tanner that theology’s work is out in the world. But it also means that theology’s audience is out in the world too. It is tempting for theologians to stay inside the academic guild and write only for other professional theologians. Tanner chafes at these boundaries. Her Gifford Lectures are the best evidence yet of her identity as a public theologian. This identity as a public theologian does not mean that her theology is easy to read, or that pastors will find in it an abundance of ready-made sermon illustrations. (A few of those would be welcome in Tanner’s writing!) What this identity means is that the audience for Tanner’s theological work begins with the church and extends far beyond the circle of Christian faith. Her theology has its roots in sources and assumptions distinctive to Christianity, but it makes proposals that address the concerns of the wider community. It offers recommendations for human life in general, not just for Christian life, confidently engaging other voices in the public square.

In the contemporary Western context, Rowan Williams has distinguished an appropriate “procedural secularism,” which refuses to give advantage or preference to any one religious community over others, from a problematic “programmatic secularism,” which seeks to rid the public space of all religious allegiances. With Williams, Tanner embraces the former. She does not assume that Christian convictions deserve a privileged place in public discourse, but she insists that Christian theology is not a purely intramural exercise. As a theologian, she seeks to join a larger civic conversation with the goal of addressing the issues that concern our common creaturehood in all its social and ecological ramifications.

Some public theologians attempt to gain a hearing for their proposals by sanding off the sharp corners of Christian belief, downplaying distinctive Christian claims about Jesus Christ, for example. Tanner’s public theology does not take this route. Christ is for her the key to what God is doing everywhere in the world. Tanner makes Christian theology compelling not by diluting its distinctiveness but by showing the radical implications of basic Christian claims for the needs and concerns of all people.

A version of this article appears in the July 5 print edition under the title “From God-talk to God’s work.”