How do we help children weave a healthy faith?

Meredith Miller uses the metaphor of a spiderweb to offer Christian parents and caregivers a new paradigm.

Woven

Nurturing a Faith Your Kid Doesn’t Have to Heal From

“How do I talk to my kids about God?” has always been a popular question among parents, and it seems to be even more popular now, with increasing numbers of people healing from the wounds Christianity gave them. Even for those who haven’t been harmed by the church, conversations with children about God can be difficult to navigate. Meredith Miller wrote Woven to give parents and other caregivers a paradigm for talking about faith with children. She believes that teaching kids about God isn’t a one-size-fits-every-family situation, so she offers a variety of guidelines and tools.

It’s tempting for parents to do nothing or to wait until their children are older. Miller warns against this approach, because “doing nothing isn’t neutral.” Much of a person’s view of the world is developed in childhood, and a child may interpret the absence of faith discussion as deprioritizing faith. Parents may be hesitant to talk to their kids about faith because of the possibility that the children will be hurt by Christianity. However, Miller notes, all children will learn about God one way or another, and what they learn about God outside the family may not be life-giving or invite their curiosity. If parents believe that it’s important to include a positive view of God in their children’s lives, they should start these conversations early.

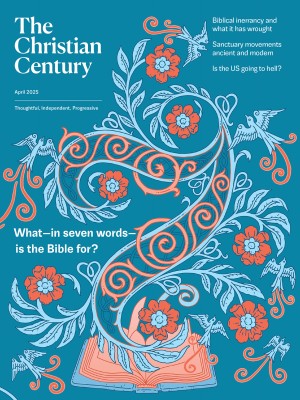

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Miller uses the imagery of a spiderweb as a metaphor for how faith should be constructed. If our faith is built of blocks, doubts will slowly create cracks in the wall, and the wall will eventually fall down. Each question wears away at the blocks, and depending on where the wear is, the wall may not recover. Alternatively, a spiderweb is strong yet flexible; it can withstand pressure without breaking. Similarly, Miller argues, a child’s faith should be able to withstand pressure. Nobody benefits from a faith that’s so rigid that one doubt will bring down everything.

One of the tools that Miller offers for helping children develop a strong yet flexible faith is a pedagogical method called spiral learning, “an educational strategy where teachers circle around important ideas again and again, over time, on purpose.” Implicit in this model is that adults have more than one opportunity to talk to kids about God; the spiral indicates that topics will be revisited, each time with more complexity and nuance. Miller notes that spiral learning can be applied to many aspects of faith, from attributes of God to Bible stories.

People often use Christianity to create moralistic lessons or rules for children to follow. This approach, Miller argues, is an unhelpful way to view religion: “Instead of asking, How might we follow Jesus together? moralism asks, Can Christianity help me (or my kid) be a good person?” Seeing Christianity as a path to being a good person instead of a path to knowing God instrumentalizes faith, making it transactional rather than transformative. Using religion to make children good also prioritizes obedience over relationships. Children learn that if they obey God (and their parents), they’re good; if they don’t obey, they’re bad. Miller argues that obedience should be a result of trust in God, not something that comes before it. If taken too far, an adult’s desire for good or obedient children may become a desire to control the children rather than invite them to explore who God is.

If a parent’s goal is to help children get to know God, Miller writes, God should be central to their discussions of Bible stories. Bible stories typically focus on the people and how they interact with God, which is understandable because we’re also people who are figuring out how to interact with God. Yet focusing on biblical characters, Miller proposes, leads to searching the Bible for principles that make us good or bad, bringing us back to moralism. Children learn that they should be faithful like Noah, obedient like Moses, brave like Esther. If they can be as good as the people in the Bible, God will reward them.

By contrast, Miller writes, “the point of the Bible is not to provide principles, but to tell the story of what God is doing in the world.” Reading the Bible to gather principles rather than to get to know God better contributes to building a wall of faith rather than a web. A better way to approach Bible stories is to ask how God behaves, what that means about God, and if God can be trusted.

Knowing how to have conversations about God with children can be intimidating, and Woven is an excellent place to start. Miller provides accessible ideas, practical strategies, and tools for helping kids to know God through experience as much as through conversation. Woven is essential reading for anyone who interacts with children in a religious setting.