Mushrooms at the table?

People have long tried to trace a connection between the early church’s eucharistic practice and psychedelic substances. Scholars aren’t convinced.

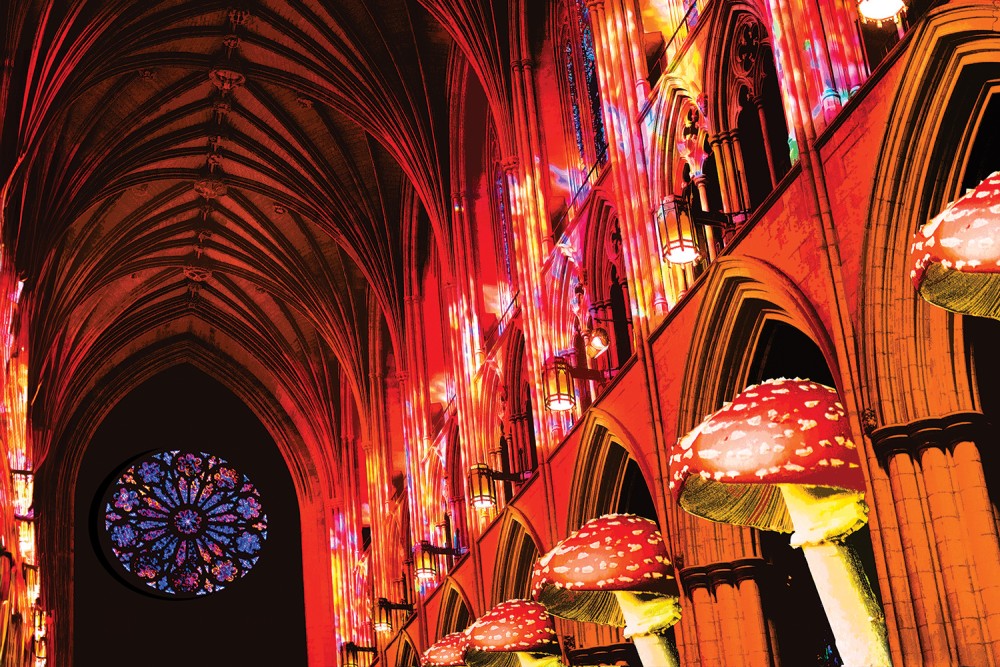

Century illustration (Source images: Ryan Arnst on Unpslash & Andrew Ridley on Unsplash)

In the tumultuous 16th century, a Dominican friar named Giordano Bruno argued that the universe was infinite and had no celestial body at its center. He also believed in the transmigration of the soul, also known as reincarnation. His execution by the Roman Inquisition on February 17, 1600, which prefigured the more famous heresy trial of Galileo, made him one of the early martyrs of modern science—despite his clear spiritualist bent.

“Unless you make yourself equal to God, you cannot understand God,” Bruno preached. “It is within our power to strip veils and coverings from the face of nature,” to illuminate those who “could not see their own image in the innumerable mirrors of reality which surround them on every side.”

Bruno’s ideas are sometimes highlighted by those who argue that there is a history in the church of a Eucharist fueled by sacred plants and fungi with psychedelic properties. Brian Muraresku argues just this in his 2020 book The Immortality Key: The Secret History of the Religion with No Name. The lawyer and writer subscribes to the “pagan continuity theory,” a speculative idea that a secret tradition dating back to the Eleusinian mysteries of ancient Greece has been kept alive by an underground network of witches and wise men through the use of mind-expanding plants and drugs. What passes for Holy Communion in the church today, he suggests, is just a pale imitation of these secret, age-old rites. Today’s wafer and wine, Muraresku writes, can be seen as a “placebo Eucharist.”