It began with a diagnosis. My 68-year-old father, a Presbyterian minister, had a brain tumor. He lived with the cancer for almost two years, while my mother and brothers and I lived with the anticipation of his death. Each of us dropped what we were doing to participate in giving care, and our world became small, confined to my parents’ house in Philadelphia, the blocks between the house and the park where Dad pushed his walker, and the cancer center.

My frame of vision narrowed around my family. Within these new parameters, small things at the tips of my fingers came into focus. The bright faces of radishes and dahlias at the market in the park. My mother’s silver hair. My new husband’s face, softened in sleep. I was sensitized to the pleasures of the proximate, even pleasures tucked inside the grotesque. Dad’s blue eyes were as bright as glass, though his hair grew in patches and his face was swollen.

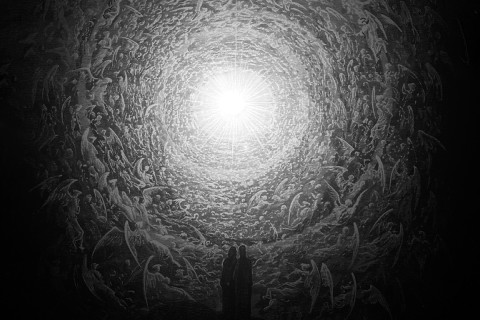

We were mourning, yes, but we were mourning the end of a joyful life, and these tokens seemed congruous with our memorial. What comes most quickly to mind when I remember that time is not a feeling of despair but the visual beauty that made the despair bearable. Intimacy with my father while he died clarified my gaze to see the presence of grace.