The power of a swim-in

In 1964, Mimi Ford jumped into a pool—and changed the course of history.

My parents purchased the home I grew up in not because of the in-ground pool but in spite of it. Mother was terrified of water. We kids had no idea how to swim. And pool maintenance was the last thing on Dad’s bucket list of desirous things to learn. But after two years of looking at an empty concrete hole, we painted it blue and poured in 55,000 gallons of water. Childhood suddenly changed course.

On many a summer Sunday afternoon in the 1960s, our family hosted friends who chose to come for what we called “Seven Summer Sunny Sunday Swim-Ins.” Tubs of ice cream created a party spirit. Wet towels hung on the chain link fence. Neighbors put up with the noise.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

On one memorable Sunday in 1967, an urban ministry friend of the family pulled up in a school bus with 35 Black kids from Chicago. Their presence in our backyard made for a beautiful sight in an all-White neighborhood. But it was also terrifying, because none of the kids knew how to swim—and this didn’t deter them from spontaneously jumping into either end of the pool. Lifeguards were never part of our Sunday swim-ins. Instead, we had well-meaning adults who sipped lemonade in lounge chairs and who, we must’ve assumed, would jump in if needed. The fact that no kid perished that day is among God’s greater miracles involving water.

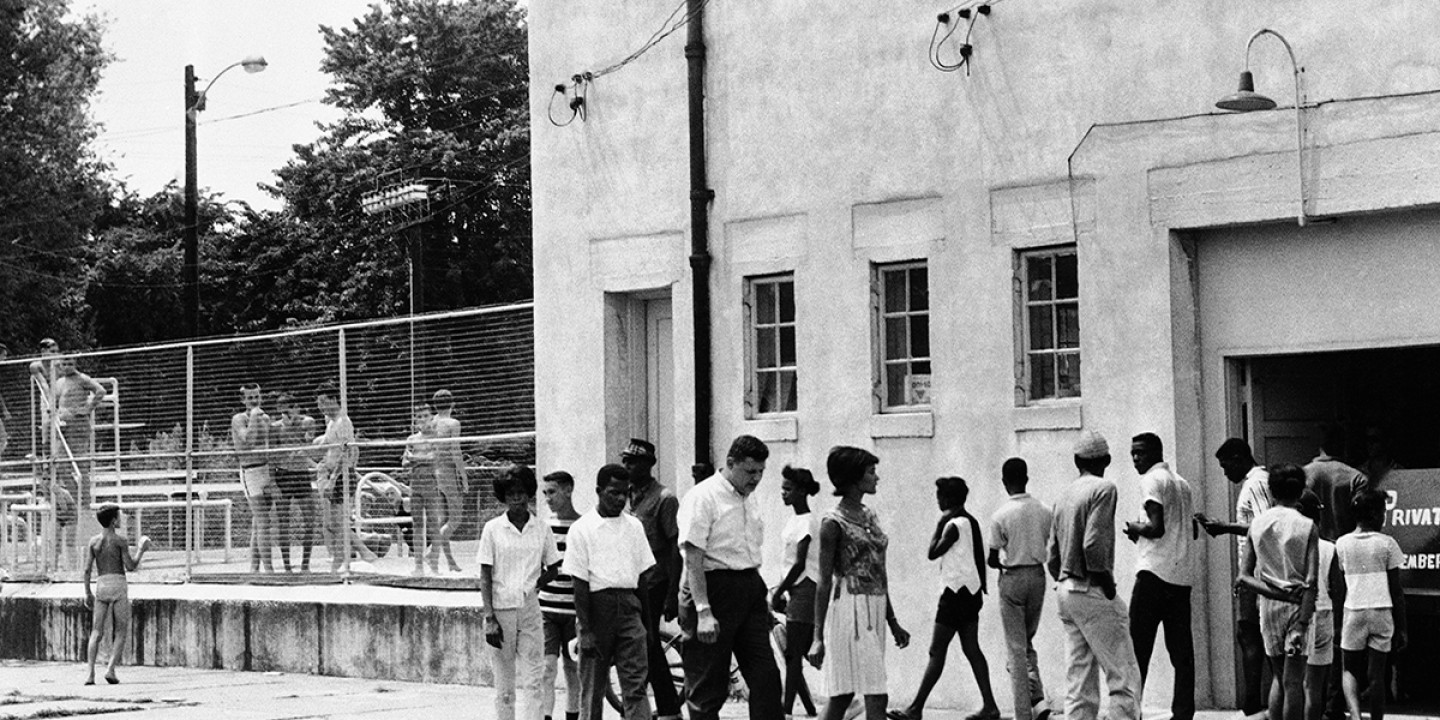

That the kids couldn’t swim is part of the racial history of swimming pools in America. White Americans are twice as likely to know how to swim as Black Americans. Despite a wave of investment that built thousands of public pools across the country during the 1920s and 1930s, including in poor, immigrant, and working-class neighborhoods, predominantly Black neighborhoods were mostly left out. When courts in the 1950s began to call for the desegregation of municipal pools, droves of White swimmers abandoned them. A building spree of pools in private clubs and homes signaled a new privatization of recreation.

In 1959, city officials in Montgomery, Alabama, chose to drain and close a public pool rather than comply with a court order to permit Black residents to swim there. For nearly a decade, Montgomery’s zoo and all of its city parks were shuttered, all to lash out against Black access. Similar closures happened at bowling alleys, roller skating rinks, and amusement parks across the country. Even the Federal Housing Administration promoted private recreational facilities (where discrimination was legal) over public ones.

In June 1964, a group of integrationists conceived of a swim-in at the segregated Monson Motor Lodge in St. Augustine, Florida. Two White activists rented a room so that several Black activists could jump into the pool with them as guests. Only a few of the Black activists knew how to swim, among them 17-year-old Mimi Ford. An iconic photo from that day, taken minutes before Ford’s arrest, shows her screaming in horror as the angry White hotel manager pours muriatic acid into the water beside her.

The photo appeared on newspaper covers around the world, stirring outrage even in the White House. Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 the same day. Who would’ve guessed the momentous role that a swim-in might play?

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “The power of a swim-in.”