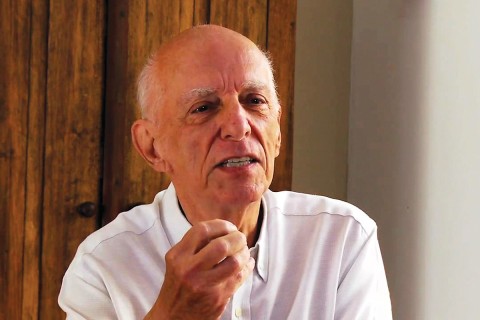

Rubem Alves builds altars of word and song

The bold visions of the grandfather of liberation theology

“I don’t know if I believe in God,” Rubem Alves once told a reporter. “But I know I’m a builder of altars. I build my altars with poetry and music. The altars must be beautiful. I build them before a deep, dark, and silent abyss. The fires I light in them illuminate my face and warm me. Yet the abyss remains the same: dark, cold, silent.”

Alves is not for everybody. He is no good for ministries with the goal of instilling proper theological constructs into their believers or stacking doctrinal scaffolding for the protection of their people from the void. He isn’t safe or easy. And yet, the altars he builds are not for him alone.

From the rubble of crumbled convictions piled upon lost loves, Alves builds as we gather around. With beauty there, he reveals to us the presence of an absence. Abysmal, perhaps, it is also warming and stirring. For this is the place (and perhaps the only place, he says) where there still might hover something of a spirit, where there may be an inkling, a hunch, a prescient spring to the step, blush in one’s cheeks, a wish or a desire for what might yet be.