The language of liberation: Black Lives Matter symposium

Disaster is understandable for black lives—they are antagonists in a narrative of humanity written to serve white supremacy. To say "black lives matter" is to interrupt this story.

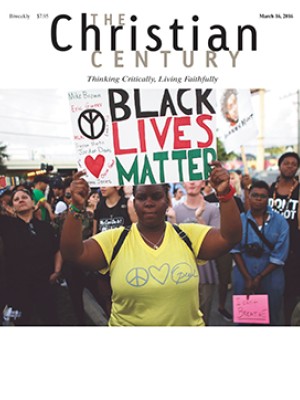

The Black Lives Matter movement that has unfolded in cities and on campuses across the nation is writing a new chapter in black people’s struggle for liberation. We asked writers to reflect on what the movement has accomplished, where its energies should be focused, and what implications it has for churches. (Read all responses.)

Coretta Scott King said, following the death of her husband, Martin Luther King Jr., “Freedom is never really won. You earn it and win it in every generation.” A look at the past 60 years proves the veracity of her words. Whether the phrase was “freedom now,” “black is beautiful,” “black power,” or “black lives matter,” historically they’ve referred to the same goal of liberation. The slogans are permutations of the enduring struggle against white supremacy. That struggle is not against the police, but it does address a racist, classist legal system.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The struggle is not against white people, yet it recognizes that the privileges afforded to whites began with the attribution of full humanity to white men only. The slogans that invoke the struggle for liberation are emblematic of an enduring problem: ongoing doubtfulness about black humanity. Are black people fully human? Black humanity has remained suspect in the imagination of “a world that looks on with amused contempt and pity” (to quote W. E. B. Du Bois). This “watching world” claims an authoritative voice, defining the dominant understanding of human life for black people as well as whites.

The introduction of Africans en masse to the Americas involved an ideology that legitimized buying and selling them as chattel. Wendell Berry argues that whites didn’t go to Africa because of race; they did so because they could. They had the means to enter Africa and take what they wanted. Race logic was birthed as an ideology of difference, a financially incentivized ideology to legitimize the lucrative use of slave labor by people who became “white” in the assembling of the new world. Race logic made a profit-based distinction between black flesh and white humanity.

Since the time of slavery, travestied black figures evolved into many different types, flowing from the imagination of white authors onto pages, stages, and screens. These depictions of black life have had little to do with actual black people and everything to do with efforts to stabilize an anxious white psyche as it struggles to know and to maintain its idealized self. Disaster is understandable for black lives—they are antagonists in a narrative of humanity written to serve white supremacy. To say “black lives matter” is to interrupt this story in a world that values life according to its proximity to the unstable template of white, upwardly mobile masculinity.

Seventeen-year-old Trayvon Martin was an antagonist in the story of white supremacy. Trayvon was posthumously tried for his own murder. As a young black male, he was described in court by a defense attorney as having power to turn the sidewalk into a weapon, and he was thus an obvious danger to the anxious neighborhood watchman following him with a gun. And although his killer was not white, a watching world empathized with the anxious neighborhood watchman rather than the frightened black teen, turning the killer into an avatar for an anxious white watching public that feared the possibility of that black teen in their neighborhood.

Three young black women revived the struggle for liberation as “Black Lives Matter” in the wake of the absurdity of Trayvon’s case. This iteration of the movement is not speaking from within the black church like the King-led civil rights movement. The times are different, and so is this movement. The story of white supremacy is dynamic, adapting in real time to evidence that it is a lie. Like an infection that refuses to let an antibiotic win, it revises itself to accommodate efforts to eradicate it.

People who heed the commandments “love your neighbor as yourself,” “do to others as you would have them do to you,” and “do justice, love mercy, and walk humbly with your God” should take seriously the work of Black Lives Matter. The veracity of this work as service to God is not in its ability to demonstrate doctrinal clarity, but in the effort to value life made in the image of God. If we are not careful to adapt with these times, we may serve racism’s efforts to retell itself anew.