No longer strangers: Ministerial group bridges left-right divide

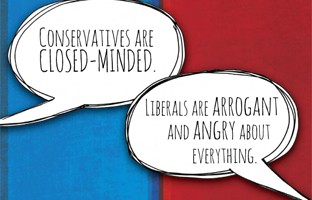

In 2009 the Richland County Ministerial Association was on the skids. Only six or eight pastors were showing up at the monthly meeting, a number that represented less than a third of the churches in this southwestern Wisconsin county. All but two of them were mainline pastors. Fifteen years earlier the evangelical pastors had split off and formed their own association. The culture wars were hot at the time, with Christians clashing over abortion laws, homosexuality, the inerrancy of scripture, gender roles, creationism, and politics.

One of the two conservative evangelicals who still attended the RCMA was Mike Breininger, pastor of the largest nondenominational church in the county. Liberals called Richland Center Fellowship “the flag-waving church.” RCF had a group that used flags in choreographed presentations and parades. For many years the church also performed a Passion play called The Keys, which drew some 40,000 people over the years. Breininger had been a wrestler at the University of Wisconsin, and he was known as a tough, no-nonsense leader. No one knew why he was still attending what most of his peers regarded as the liberal RCMA.

It wasn’t because he loved liberals or the RCMA. “My faithful attendance had nothing to do with a desire to see the association prosper,” said Breininger. “I was deeply concerned that the differences between the theological liberals and conservatives, and the ranting of those wanting everyone else to adopt their agenda, were a disgrace to the name of Christ. I didn’t want to lead the association. I wanted to silence it.”