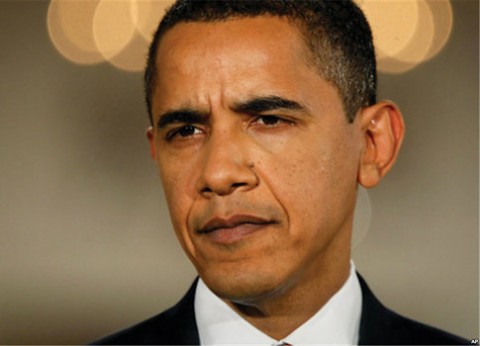

The postpartisan partisan: Obama as Christian realist

Prior to his election in 2008, Barack Obama declared that Reinhold Niebuhr was one of his favorite philosophers. This affirmation led several prognosticators to elucidate various features of the early Obama presidency in Niebuhrian terms. Indeed, his mode of governance betrays a marked Niebuhrian slant and sometimes—as in his speech accepting the Nobel Peace Prize—a Niebuhrian vocabulary. That is to say, the president seeks to recognize and embrace both the idealistic and realistic poles of Christian action. He understands Christian realism as Niebuhr defined it—a recognition that politics is inherently tragic.

Obama’s foreign policy has been a portrait of Niebuhrian realism. Idealists on both sides have attacked him—the right for not being willing to act unilaterally in the quest to reshape the world, the left for not relinquishing the use of coercive military force. In the case of the uprising in Libya, for example, Obama waited for a coalition to form before directing American forces to command and coordinate the efforts of NATO forces. In preparing for intervention, Obama went beyond the calls for air strikes and a no-fly zone, while insisting on a limited American involvement. Having made that decision, Obama went on national television and argued that intervention was the right thing to do, and he gave three reasons: failure to act would leave a stain on America’s conscience; America had an interest in the outcome in Libya, since American leadership in the region would be adversely affected by a refusal to act and by a resultant humanitarian crisis; and the costs of action were acceptably low.

In this mixture of arguments one can see the calculations of a pragmatist balanced by the hopes and desires of the idealist. The Christian realist takes the opportunity at hand to accomplish a proximate good.