Film feast: Insights from the Montreal World Film Festival

During this year’s Montreal World Film Festival, I spoke with Suayip Adlig, a producer of the Iraqi Kurdish film Narcissus Blossom. I liked the picture; it’s one of those little gems that turn up at Montreal in small, out-of-the-way screening rooms in the late afternoon. The film is a gritty, realistic portrait of the U.S. role in the betrayal of the Kurdish people’s desire for independence.

Earlier this year, Narcissus Blossom won an award from Amnesty International at the Berlin Film Festival. Now Adlig has set his sights on the U.S., with no less a goal than the Academy Awards foreign-film competition. Before he can qualify for that competition, however, he needs to find a theater that will show his film in Los Angeles for one week. He will have a tough sell, given the current political climate, but Adlig is not discouraged. He says he is looking for “one courageous American theater owner.”

As Narcissus Blossom opens, a Kurdish family is watching a television report on the signing of the 1975 Algiers Accord, an agreement between Iran and Iraq. The accord was arranged by Henry Kissinger, President Ford’s secretary of state. Earlier, Kissinger had promised the Kurds full U.S. support via Iran in their struggle for freedom from Iraq. Then, in a diplomatic tap dance, the Kurds were abandoned in a war they could not win alone.

The Iraqi Kurds were betrayed again in 1991 when the first Bush administration, which had promised support for a Kurdish uprising against Saddam Hussein, decided to halt all fighting against Saddam to preserve a “united Iraq.” Ironically, the 2003 invasion under George W. Bush’s leadership has moved the Iraqi Kurds closer to the independence denied them earlier. This outcome is certainly not part of the Bush vision for the Middle East.

The Montreal festival performs a special role among North American festivals. Unlike the Toronto festival, which is largely a showcase for major productions and is heavily influenced by U.S. film companies, Montreal is a place for independent filmmakers from outside North America to show their work. Iranian director Majid Majidi, for example, introduced Children of Heaven and The Color of Paradise at Montreal. Both enjoyed successful runs in U.S. art-house theaters and in DVD sales. Adlig hopes to duplicate Majidi’s success.

During the festival, news reached Montreal that Kurdish leader Massoud Barzani had threatened to secede from Iraq unless he was allowed to fly the Kurdish flag instead of the national flag. Narcissus Blossom, codirected by Masoud Arif Salih and Hussein Hassan Ali, depicts the passion behind such a threat. Its insights need to be understood by American media and political decision makers.

The film depicts the birth of the peshmerga, or “those who face death,” the Kurdish militia formed in 1975 to fight for an independent Kurdistan on the Iran/Iraq border. Today, the peshmerga provides the region with its military arm. They are a fighting force motivated not by religious radicalism, but by a desire for independence.

Another film based on the struggle for independence is Barakat! directed and written by Djamila Sahraoui. Set in a coastal town in Algeria in the 1990s, Barakat! tells the deceptively simple story of Amel (Rachida Brakni), a woman doctor who is searching for her husband, who has been kidnapped by an underground Islamist group. The husband, Mourad, is a journalist who has written columns attacking one of the Islamist factions, several of which are struggling for control of Algeria against the country’s secular government.

Acting on a lead that tells Amel that her husband is being held in the mountains, she drives there with an older woman, a nurse who fought in the war of independence. The women drive into a trap and are held overnight by a man the nurse had aided in the war—a connection that saves both their lives.

Sahraoui’s film presents one small story in an epic of a people struggling through the chaos of a postrevolutionary period. When one character takes the doctor’s pistol and throws it into the sea, he shouts, "Barakat!"—which is translated as “Enough!” In Arabic, barakat means blessing or grace. The translator may have determined that English-speaking audiences would not understand blessing or grace in that context, but blessing and enough are not really that far apart in this context, since the rejection of the gun becomes a blessing.

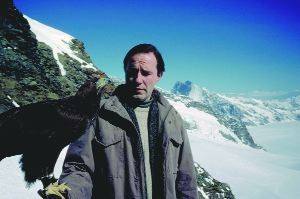

In a film from Switzerland, director Hans-Ulrich Schlumpf takes his character, successful stockbroker Fred Böhler (Stefan Kurt), on two journeys: one a struggle for life after a serious accident, and the other a journey into the wilderness of Alaska. Ultima Thule: A Journey to the Edge of the World is about one man’s midlife crisis. Bohler reconsiders his earlier life choices in a coma-induced dream sequence. He imagines that he is flying with an eagle over Alaska’s mountains and frozen tundra. As he walks through the ice fields and the wilderness, he recalls his college plans to become a natural scientist, a dream he had abandoned.

Böhler then imagines that he’s in a different section of Alaska, flying over the crumbling buildings of an abandoned mine. In his dream he enters a bar there and is served by a man who seems to know him, a man revealed as the surgeon who is trying to save his life. Ultima Thule provides a metaphor for crisis, struggle and hope.

Hell in Tangier is a Belgian film based on the true story of Marcel van Loock, a tour bus driver arrested for smuggling drugs out of Morocco. The tour company owner and another driver are guilty. The innocent Van Loock is betrayed by his colleagues and sentenced to five years in an overcrowded Tangier prison. Director Frank van Mechelen persuaded Flemish actor Filip Peeters to take the role of van Loock.

While Mechelen includes a few surprising acts of human decency inside the prison, he harshly portrays both the Moroccan prison system and the Belgian officials who do little to help van Loock. When his wife led a public campaign in Belgium for clemency for him, van Loock’s prison term was reduced and he returned home in a wheelchair. The campaign led to a change in national policy—today Belgian citizens arrested in at least some foreign nations can serve their sentences in Belgian prisons.

Both the ecumenical jury, composed of three Protestant and three Catholic jurors, and the main jury gave the festival’s chief prize to a Japanese film, A Long Walk, directed by Eiji Okuda. The film was cited for the manner in which it creates a transforming moment for a retired widower alienated from his daughter, a five-year-old girl abused by her mother, and a lost teenage boy.