Century Marks

Wrestling with texts: Feminist scripture scholar Phyllis Trible says that after she lectured on the horrific story in Judges 19 about the unnamed woman who was gang-raped, murdered and then dismembered, a woman came up to her weeping, saying that she didn’t know the Bible contained such a story. She said that she had been raped and psychologically murdered, and that story of the woman in Judges 19 was her story. Rather than being offended by the inclusion of this story in the Bible, this woman felt blessed by it. “It helped me to see that you never throw away any part of the Bible,” remarks Trible. “You never know when and in what situation it will relate to a reader.” Trible says the Bible is full of both blessings and curses, and it is not always clear which is which. To get the blessing we have to wrestle with texts, just as Jacob wrestled all night with an angel. But as in the case of Jacob, who emerged from his wrestling match with a limp, the blessing may not come on our own terms (interview in Biblical Archaeology Review, March/April).

Dare to challenge God: In the high Middle Ages university education took the form of disputations. Teachers asked questions, students prepared responses both pro and con, and advanced students refuted those responses. It wasn’t that the answers to the questions were in doubt; rather, this was a way for students to deepen their understanding of Christian tradition and relate it to their own experience. Something like this ought to happen in contemporary preaching, argues Marilyn McCord Adams. Preachers should question and challenge the authority of the faith—not to undermine faith, but to deepen it and to help listeners address the questions that naturally arise from life’s situations. As it was for Abraham and Job, this is a measure of the friendship between God and ourselves, for true friends will challenge and question each other (Expository Times, March).

Scapegoat: Rachel Srubas knows what it’s like to be scapegoated. Growing up with an alcoholic parent, she acted out the dysfunction in her family, and for that her parents put her in a psychiatric ward. But her people, being Armenian, were also scapegoated—by the Turks, who tried to exterminate them in the early 20th century. Some Armenians still want revenge for what happened to their ancestors, says Srubas. But Archbishop Khajag Barsamian of the Armenian Church of North America suggested another response in his 2005 Easter letter: “Our church does not . . . conceive of Christ as some kind of human sacrifice or scapegoat, whose humiliation ‘purchased’ salvation for [humankind]. . . . Christ’s death was God’s way of standing shoulder-to-shoulder with all the deaths that had gone before. And of anticipating those that would come after. . . . The scars we still bear today, the losses we have endured, . . . Christ has borne before us. Borne them in anticipation of our own afflictions. Borne them out of his love for us, in triumph as well as tragedy” (Weavings, March/April).

Class virtues: David Brooks, New York Times columnist, likes to sing the praises of values such as industry, temperance, prudence and thrift. These are all middle-class values, according to William Deresiewicz, values that he himself holds because he belongs to the middle class. But there’s a dark side to all these values: narrowness, prudery, timidity, meanness, hypocrisy and self-conceit. Though working-class people are reputed to be less temperate, thrifty, industrious and so on (whether these descriptions are fair or not), “working-class life breeds its own virtues: loyalty, community, stoicism, humility, and even tolerance,” Deresiewicz says. Of course, not all working-class people exemplify these virtues, he says, but “if only because of their limited possibilities in life,” working-class people tend to “care more about their families and their friends and the places they’re from than they do about their careers” (American Scholar, Winter).

No comment: “We have before us in the White House a thief who steals the country’s good name and reputation for his private interest and personal use; a liar who seeks to instill in the American people a state of fear; a televangelist who engages the United States in a never-ending crusade against all the world’s evil, a wastrel who squanders a vast sum of the nation’s wealth on what turns out to be a recruiting drive certain to multiply the host of our enemies. In a word, a criminal—known to be armed and shown to be dangerous” (editor Lewis H. Lapham, “The Case for Impeachment,” Harper’s Magazine, March).

Rust-Oleum for Kalamazoo: Due to plant closings, Kalamazoo has in recent years gone the way of other rust-belt cities, with a poverty rate of 25 percent and a deteriorating downtown. So a group of anonymous philanthropists, working with the superintendent of public schools, has prescribed an unusual remedy—free college tuition for all students who graduate from the city’s public school system and are accepted at a public community college or university in the state of Michigan. Called the “Kalamazoo Promise,” the program is already providing incentive for suburbanites to move into the city, causing an increase in property values. What is not known yet is whether the program will increase employment in the city (Wall Street Journal, March 10).

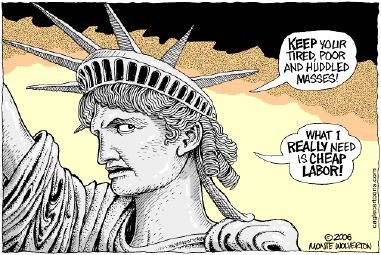

Social gospel still needed: TV news reporter Sam Donaldson once said that there was a basic conflict between Ronald Reagan the man and President Reagan the politician. If you were down on your luck, Reagan would give you the shirt off his back. But then he’d sit in the Oval Office in his undershirt, signing legislation that would throw kids out of school lunch programs and take people off welfare rolls, all in the name of fiscal responsibility. “He had a good heart, but when it came to his ideology, his philosophy [was] ‘off with their heads’” (from David L. Holmes, The Religion of the Founding Fathers, Oxford University Press).

Building character: In college sports, coaches are judged by their wins and losses, but seldom for their character or their style of leadership. Professors face course evaluations from their students. Why not coaches? Philosopher Gordon Marino suggests that college athletes should get a chance to say whether the coach treated everyone fairly or whether he or she was approachable and open. If the justification for sports in higher education is that it builds character, then judging the character and conduct of coaches seems in order (Chronicle of Higher Education, March 3).

Seriously: LandoverBaptist.org is a satirical Internet site that sells T-shirts reading “Intelligunt Desine” and “Homeskooled,” a thong that says “Jesus Votes Republican” and a bumper sticker with the question “Who Would Jesus Bomb?”