Happy pastors: What is happening to Protestant clergy?

Something has gone terribly wrong with Protestant clergy. The majority of them say that they are “happy, content,” as a recent Christian Century news headline proclaims (March 27-April 2). And since the Century says it, it must be true. Evidence comes from polls backed and perpetrated by the Lilly Endowment, the National Opinion Research Center and the Pulpit and Pew research project at Duke University.

What has gone wrong? The Protestant clergy is not living up to its stereotypes. For years other polls and articles or bishops and others who deal with church conflict have assured us that things are amiss. Protestant clergy are supposed to be sad. Instead, more than not are more or less happy. Most have never doubted their call to ministry and have never thought of leaving the ministry. Few spend time fighting about issues like the ordination of gay people, issues that tear denominational conventions apart.

Of course, there are problems in many congregations and dark sides to every pastorate; we live in an imperfect world. The latest poll data does not present pastors as Pollyannas. Some problems, say the Duke people, need attention. While pedophilia has not been as big an issue in Protestantism as in Catholicism, you don’t hear a peep of Schadenfreude from Protestants. There is, first of all, a reservoir of profound sympathy and empathy toward the Catholics. Second, an awareness that “adult male-female liaisons” blight some Protestant ministries keeps Protestant clergy from being or sounding self-righteous.

A question: if so many pastors are “happy, content” in mixed and restless sorts of ways, why don’t more of them commend pastoral ministry to the brightest collegians in their flocks? They used to; the call to ministry often came through the voice of one’s pastor. In recent years, however, fulfilled clergy must have believed only the “moan and groan” from some colleagues. All know the grave problems that can come with demoralizing pastorates. They have lost confidence in their impulse to invite young men and women to join, as their first vocation, the larger numbers of “second-vocation” callees to ministry. Will they regain their confidence?

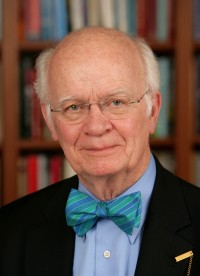

We historians may not know enough about the sociological and theological studies of ministry to engage in deep analysis. But we do like stories. When my friend F. Dean Lueking began to write a memoir, I reminded him of publisher William Sloan’s advice: People who read memoirs are not saying, “Tell me about you!” They are usually saying, “Tell me about me, using your experience and story as a mirror, a template, a possible model for me.” Lueking was guided by that insight as he wrote The Last Long Pastorate: A Journey of Grace (Eerdmans).

Of course, “I have an interest” in making people aware of this book, as we are supposed to acknowledge those days and as I happily say this time. Several times Lueking, whom I have known for 55 years, identifies me as “the closest of his close friends,” and I’d say the same of him. But I can’t let “interest” disqualify me from commending his book to you. It records a 44-year pastorate at Grace Lutheran Church in River Forest, Illinois.

He tells of the ups, which were really up, and the downs, including an epic church-property court case struggle, that go with such a ministry. While the names of members won’t mean much to anyone outside of the congregation, they can be stand-ins for the people we know wherever we live. I like to read such a memoir every year; last year it was Richard Lischer’s Open Secrets. Such books appeal to the “happy, content Protestant pastor” in me.