Black and white thinking

Read Jonathan Tran's cover story on the new black theology

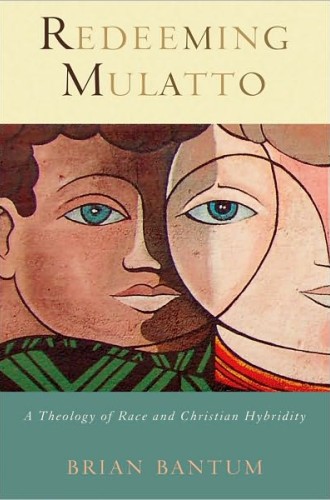

Redeeming Mulatto presents a complex argument about theology and race. It is impossible to do it justice in a short review. Brian Bantum persuasively challenges traditional ways of thinking about race in the United States by theologically retrieving interracial identity as an important category that has been unduly neglected. In this way he addresses the American tendency to understand race relations in terms of the binary opposition between black and white.

Bantum describes the historical experience of being mulatto/a by suggesting that race in the U.S. functions like religion or as a form of discipleship into which we are all recruited. He develops a mulattic Christology in which Christ is a tragic mulatto who refuses racial kinship identity precisely by occupying a neither/nor space of in-between existence. Finally, he describes how we can become reborn into genuine Christian discipleship beyond the constraints of racial belonging and loyalties.