Fighting atheist

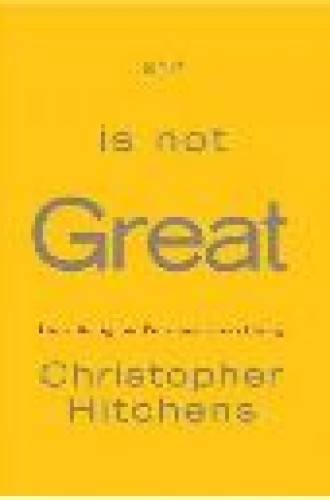

After you have written books attacking Henry Kissinger and Mother Teresa, what is left, really, but to write a book attacking God—or rather, since God does not exist, attacking all who believe in God? So Christopher Hitchens, the brilliant bad boy of Anglo-American high-culture journalism, must have concluded.

Though now an American, Hitchens still writes in the best tradition of British polemic—clever, vicious and very funny. No sense of political correctness, moreover, restrains him: Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Buddhism—you name it; they are all stupid, and all dangerous.

In olden times, he argues, when ignorance abounded, there were excuses for being religious: “The scholastic obsessives of the Middle Ages were doing the best they could on the basis of hopelessly limited information.” But now science has provided us with correct ways of understanding the world, and thus “religion spoke its last intelligible or noble or inspiring words a long time ago.” Arguments from the order of the universe to the existence of God collapse in the light of modern science. Appeals to revelation are absurd once we know that there are many different purported revelations.

Judaism, Hitchens writes, rests on an ancient text whose barbaric laws and false history far outweigh its “occasional lapidary phrases.” Also, “the ‘new’ testament exceeds the evil of the ‘old’ one.” Jesus probably did not exist, and the center of his story is in any event appalling: “I am told of a human sacrifice that took place two thousand years ago, without my wishing it and in circumstances so ghastly that, had I been present and in possession of any influence, I would have been duty-bound to try and stop it. In consequence of this murder, my own manifold sins are forgiven me, and I may hope to enjoy everlasting life.”

Islam, he continues, is a fraudulent mixture of bits of Judaism and Christianity. Hinduism has done India terrible harm. The British were about to grant the country independence anyway, but Gandhi turned what could have been a healthy secular movement toward a modern state into a disastrous attempt to return to the values and customs of the ancient Indian village. Buddhism fries the brain: “The search for nirvana, and the dissolution of the intellect, goes on. And whenever it is tried, it produces a Kool-Aid effect in the real world.”

Hitchens insists that religions are not just silly but also dangerous. Jews, Christians and Muslims are always fighting on behalf of their faiths. Sri Lanka is torn apart by Hindu-Buddhist violence. Your own religious neighbors may seem friendly enough, but do not trust them: “Many religions now come before us with ingratiating smirks and outspread hands, . . . competing as they do in a marketplace. But we have a right to remember how barbarically they behaved when they were strong.” And do not think those days are over: “As I write these words, and as you read them, people of faith are in their different ways planning your and my destruction.” Religion poisons everything.

To be sure, religious folks do good as well as evil. Hitchens particularly admires Martin Luther King Jr. But at the core of what King taught, Hitchens maintains, were simple human values; King expressed them in Baptist sermons because that was the language shared by the people with whom he was communicating. On the other side of the ledger, Hitchens admits that nonreligious regimes, like Stalin’s and Pol Pot’s, can do terrible things. But they do so only to the extent that they become quasi-religions, with sacred texts, absolute authorities and measures for condemning heretics. “Totalitarian systems, whatever outward form they may take, are fundamentalist and, as we would now say, ‘faith-based.’”

It would be hard to find the standard arguments against religion presented in livelier form than they are in God Is Not Great. The book reads quickly, and even for most religious people grunts of annoyance will be balanced by regular laughter. Hitchens has not forged such a successful career without knowing how to entertain. Nevertheless, this is a flawed and frustrating book.

First—how to say this politely?—it is full of mistakes. George Miller, we are told (actually it was William Miller), founded a new sect in upstate New York in the 1840s, but the group soon disappeared. More than 20 million Seventh-day Adventists will be surprised to hear it. Hitchens reports in an excited tone, “One of Professor Barton Ehrman’s most astonishing findings is that the account of Jesus’ resurrection in the Gospel of Mark was only added many years later.” Well, it is Bart rather than Barton (names are not Hitchens’s strong point), and scholars generally recognized long before Ehrman was born that the ending of Mark is a later addition.

T. S. Eliot was an Anglican rather than a Roman Catholic. The Talmud is not “the holy book in the longest continuous use.” Solipsists are people who doubt the existence of a world outside themselves, not people who are ethically self-centered. The ontological argument is not even close to the silly syllogism described on page 265. Hitchens writes that it is “often said that Islam differs from other monotheisms in not having had a ‘reformation,’” then he goes on to correct that claim. But sure enough, 11 pages earlier he himself had said, “Only in Islam has there been no reformation.”

And so on and so on.

The errors are particularly disturbing because so much of Hitchens’s argument rests on statements that the Catholic Church teaches such and such, the archbishop of Canterbury said this, Muslims believe that. Most of these claims are simply unsupported assertions; when no sources are cited, one cannot help wondering if someone so sloppy with his facts might make up some of his quotations as well.

The second frustration of reading this book, at least for a theologian, is that its author seems not to have read any modern theology, or even to know that it exists. He does cite C. S. Lewis a few times and mentions Bonhoeffer with respect (implying that Bonhoeffer had stopped believing in God by the end), but in general his sources for contemporary Christianity are Pat Robertson, Billy Graham and Tim LaHaye. Of Barth or Tillich or Rahner—or their equivalents in other religious traditions—he has not a clue. When Hitchens wants to discuss modern interpretations of the Bible, he turns to Mel Gibson (really!).

Suppose I watched Bill Nye the Science Guy on TV, read the first three Web sites that popped up when I Googled “quantum mechanics,” talked to the junior high science teacher who lives down the street, and then wrote a book about how superficial contemporary physics has become. Readers might reasonably protest that I should have read or interviewed some of today’s leading physicists before jumping to such a conclusion.

Similarly, when Hitchens dramatically announces that parts of the Bible are not literally true, one wants to say that Origen figured that out and decided what to do about it roughly 1,800 years ago. Many theologians are thinking in interesting ways about the relation of science and faith. Thoughtful historians try to sort out how much of the inspiration of “religious warfare” has actually come from religion, and how often religion has just been the excuse for people who wanted to fight anyway.

I do not mean that there are always clear answers to the issues Hitchens raises, much less that the religious side would always win the debate. My point is simply that among serious people writing about these matters, the argument has often advanced a good many steps beyond where Hitchens is fighting it—so however good his basic questions are, and however enjoyable his style, it is hard to take his contribution to the conversation seriously.

So here is a puzzle. When I went to buy this book, the first bookstore was sold out, and the second had a rack of God Is Not Great surpassed only by the stacks of Harry Potter. No doubt good writing deserves readership, and Hitchens can certainly write. In the age of talk radio and Fox News, the complaint that he often gets his facts wrong may be an old-fashioned objection. But something more, I think, is at stake. Similar books by Daniel Dennett, Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris are selling nearly as well.

Many Americans today are scared of religion. Radical Islamic terrorists threaten the safety of major cities. George W. Bush assures us that God has led him to his Iraq policy. The local schools, under pressure, avoid teaching evolution. The Catholic archdiocese of Los Angeles is selling off property to pay victims of priestly sexual abuse. One trembles to think that many people get their picture of faith from the “Christian channels” on television. No wonder religion has, in many quarters, a bad reputation.

I think many of us—I do not mean just trained theologians, but ordinary folks in churches, mosques and synagogues as well—have found ways to be religious without being either stupid or homicidal. We are, as the cover of the Christian Century puts it, “thinking critically, living faithfully.” Not enough of our nonreligious neighbors know enough about what we believe. We need to speak up.

Repeatedly Hitchens cites some horrible thing that some religious folks did or said and then notes that mainstream religious leaders did not criticize it. Although I do not always trust his claims, I suspect that in this case he is at least partly right. Too many of us have been too reluctant to denounce religious lunatics, and because of our reluctance we risk arousing the suspicion that we are partly on their side.

Hitchens ends his book with an appeal to his readers to “escape the gnarled hands which reach out to drag us back to the catacombs and the reeking altars, . . . to know the enemy, and to prepare to fight it.” Shouldn’t one of the lessons of this book have been that comfortable intellectuals should be more careful of using words like fight? Fundamentalists of one sort or another, after all, urge their followers to fight the evils of secularism and atheism. As the battle lines are drawn between the two extremes, it seems to me that folks like those who read the Christian Century need to put aside our obsessively good manners and shout, “Hey! Those aren’t the only alternatives! We’re here too!”