Centering Chloe and decentering Paul

Womanist scholar Mitzi Smith offers resources for understanding the reception of 1 Corinthians among Black readers.

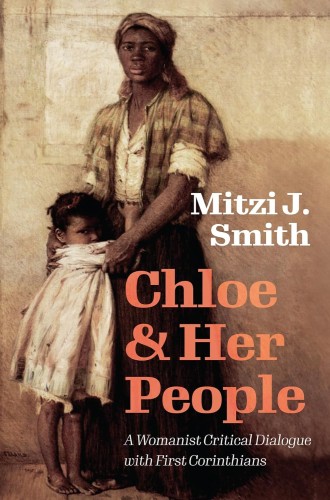

Chloe and Her People

A Womanist Critical Dialogue with First Corinthians

In Chloe and Her People, Mitzi J. Smith offers the first book-length womanist approach to 1 Corinthians. She masterfully weaves together womanist voices while engaging contemporary scholarship on 1 Corinthians and Pauline studies more broadly. Smith’s distinctive womanist approach centers Black women’s lives as she tends to “misogyny, racism, classism, dis-abilism, heterosexism, and the intersectionality of oppressions and violence.”

Smith’s discussion begins not with Paul but rather with Chloe (who appears by name in 1 Corinthians 1:11) and her people. Throughout the book, Smith decenters Paul. This is an important move since his canonical status renders especially dangerous his words that undermine women’s voices, leadership, and bodily autonomy. Offering a reading from below, Smith argues that Chloe was a freedwoman in Corinth and a leader within the Corinthian Christ assembly. Smith draws from material, literary, and other historical evidence to present how colonized Corinth’s large population of freed people should inform readings of this letter (as well as the Corinthian correspondence more broadly). This is especially true for those from whom Paul had heard rumors about the assembly’s dissension—Chloe and her people.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Highlighting how the name Chloe was frequently given to enslaved people in antiquity, Smith makes a connection that marks her crucial methodological intervention: she notes that Chloe was also a popular name for people enslaved in the antebellum United States. To this end, Smith pairs the freedwoman Chloe of Corinth with Aunt Chloe, the formerly enslaved woman (a freedwoman of sorts) in Frances Ellen Watkins Harper’s Sketches of Southern Life. Pairings of this sort run throughout the book. The pairings do not function as superficial correlations but rather as a hermeneutic strategy to allow for closer analyses of both ancient and contemporary times.

Smith notes how Paul ignores Chloe’s leadership and instead focuses on his rivalry with a male opponent, Apollos. Paul frames the rivalry as a dichotomy between spiritual knowledge and worldly knowledge. Smith resists that binary by elevating narratives of Ketanji Brown Jackson, Alice Walker, Toni Morrison, George Washington Carver, Maria W. Stewart, and Frederick Douglass—Black folk who model the integration of education and Christian spirituality. Smith persuasively argues that the Corinthian assembly may very well have disagreed with Paul’s view about such a dichotomy. She appeals to Apollos’s success as evidence.

Although I do not find the book of Acts to be as reliable an eyewitness account as Smith does, I am persuaded that to some extent it is at least as reliable as Paul’s rhetorical reconstruction of his opponent in 1 Corinthians. Smith proposes that Apollos is a freedperson from Alexandria who speaks with parrēsia (boldness) like the apostles. She then argues that Chloe and others like her may have been attracted to Apollos and his message, even over Paul. Smith depicts the intersections of freedperson status, multiple ways of knowing, and disdain from Paul as a map that connects Apollos, Chloe, and Black women.

Smith also investigates where Chloe would have been found in the matrix of Paul’s discussions of sex in relationship to lust and love in relationship to power. By elevating the experiences of formerly enslaved people after the Civil War, single Black women, and queer Black women, Smith highlights the limitations of Paul’s vision for sex as only safe in heteronormative, long-term, monogamous relationships. Furthermore, she suggests that Paul’s anxiety about an impending crisis and concerns for self-mastery prevent him from calling for the abolition of systems of domination. Smith forcefully argues that Paul’s instructions about sex are not about love; they are about lust and power. They do not account for women, enslaved people, or freed people who are mastered or could easily be dragged back into someone’s mastery.

Listening to the voices of people such as bell hooks, Paulo Freire, and Monique Moultrie, Smith turns to visions of love. In a powerful twist, she denounces the “love chapter” (1 Corinthians 13) and shows how it is embedded within Paul’s larger discourse of silencing women and denigrating his opponents. She offers Shawn Copeland’s analysis of how Paul’s depiction of love persevering has been used to cajole women (and especially Black women) into preferring a love that has longevity over one that is life-giving. Smith remixes 1 Corinthians 13, writing:

I rejected a self-less love. . . . Now three—faith, hope, and love—survive, but what I now need most is hope, hope that envisions something better, the not yet seen, the yet to be, the can be, and will be, a different love that respects her body, voice, choices, dreams, desires (sexual and nonsexual), gifts, and achievements.

One of the most forceful arguments in the book is found in a chapter entitled “Hands Off Our Hair, Paul! Reading Quarely and Transgressively to Shatter the Glass Ceiling Placed on Our Heads.” It is quite easy to see how centering Black women (and Black people more broadly), whose hair is often regulated to preserve gender and racial hierarchies, provides a powerful context for engaging Paul’s instructions regarding women’s coiffure. By engaging regulations of women’s hair and head coverings both in the United States and internationally, Smith observes that ideas of men being the head of women manifest on women’s actual heads. She argues that many Black women’s natural hairstyles resist, transgress, or quare (a term coined by E. Patrick Johnson to describe the intersection between queerness and racialized experience) normative, hegemonic standards and offer images of liberation that remove fingers like Paul’s from touching women, controlling women, or reducing them to their hair.

Chloe and Her People offers resources for understanding the reception of 1 Corinthians among Black readers. More than that, it shows how the experiences of Black people, and especially Black women, are methodologically ripe for engaging both 1 Corinthians and the communities that first read it. Smith notes in both the introduction and the epilogue that there is much more in 1 Corinthians to which her approach might be applied. Seminarians, New Testament scholars, and serious lay Bible students would benefit from such application, just as they will benefit from reading this thoughtful, critical volume.