A gospel that admits it’s a false prophecy

One of the most fascinating texts from early modern Europe is the Gospel of Barnabas.

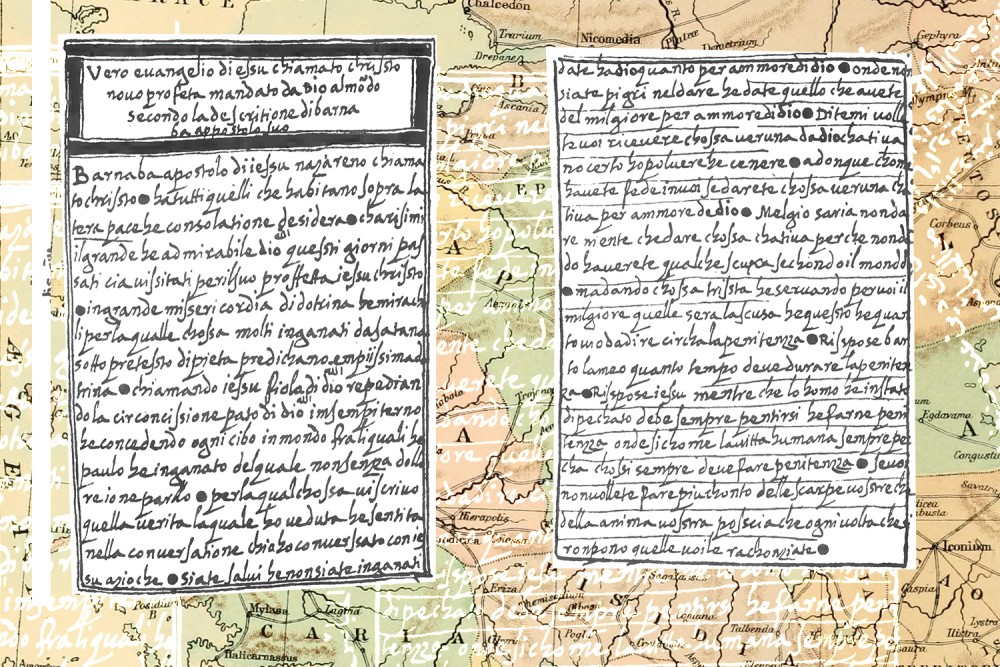

Frontispiece of the Vienna manuscript of the Gospel of Barnabas (Public domain)

Many readers are familiar with the concept of lost or alternative gospels, which were produced so abundantly in the early Christian era. Another gospel, from a much later era, might be unique in Christian literature of any and all eras. Just imagine a gospel composed by Jorge Luis Borges while Umberto Eco held his coat and Neil Gaiman took notes.

The text in question is the Gospel of Barnabas, which in its present form was probably composed in Spanish around 1600. (Every comment about its date and origins is controversial.) It offers a Jesus who in many ways is very close to the canonical figure, except that he repeatedly declares the future coming of a new prophet, who will be Muhammad. Since the late 19th century, Barnabas has become immensely popular in the Islamic world, where it is vital to polemic and proselytizing. As such, it circulates far more widely than any of the more famous alternative gospels that we know in the West.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Barnabas may have originated with the Moriscos, Spanish Muslims who converted at least notionally to Christianity but were expelled from the Spanish possessions in 1609. But the gospel is far more than a simple Muslim apologetic. Throughout this very long text, at every stage we encounter truly subversive themes of deception and illusion, which allegedly permeate all the major faiths.

This emerges spectacularly in the account of the crucifixion. Many early Christian sects had argued that the crucifixion was an illusion, a tradition inherited by the Qur’an. In Barnabas, every observer is led to believe that Judas Iscariot is actually Jesus, and he is the one who actually perishes, despite his pathetic and ineffective cries to be recognized for who he is. The author admits that he too was deceived, making him a classic unreliable narrator. At every stage, false teachers have corrupted and concealed the authentic message. That evil would only end with the coming of a definitive revelation, which might or might not be the historic Qur’an. Orthodox Christian doctrine grew from those who pretended to be disciples and proclaimed Jesus’ resurrection, “among whom is Paul deceived.”

The author declares the untrustworthiness of all texts and especially scriptures, not because they have been inaccurately delivered to humanity—an intolerable thought—but because they have been subsequently falsified. Issues of forgery, authenticity, and scribal integrity abound. Texts are fundamentally untrustworthy. In one story, the scribe Nicodemus reports finding in the high priest’s library the actual and authentic text of the book of Moses, which differs radically from the Old Testament used by the masses. The introduction to Barnabas itself likewise claims that this was the true gospel purloined from the papal library, quite unlike the vulgar gospels held out to the ignorant masses.

In another instance, Barnabas recounts at some length the relationship between Obadiah, Hosea, and Haggai, presumably the Hebrew prophets of those names, though each lived in a different era. Although the stories are edifying, the scribe Nicodemus is reluctant to report them, because “many believe it not, although it is written by Daniel the prophet.” The tale is at best apocryphal, and Nicodemus does not wish to place it in the mouth of Jesus himself—until Jesus confirms its truth by means of a miracle.

The Jesus of this gospel also tells the troubling (and authentic) Old Testament story of Micaiah, from 1 Kings 22. This obscure story reports how a faithful prophet is commanded to give a false and misleading message in order to destroy an enemy king. A heavenly angel or spirit thus inspires the speaking of false words or bogus prophecy. How are we meant to believe anything that is written or revealed? What is there to rely on in this treacherous world?

Although named for Barnabas, the book’s true hero is Nicodemus, the one who understands concealed truth. He appreciates when a document is likely to be forged or misleading and can discern truthful writings. But his honesty can only take him so far, and he needs the miraculous aid of Jesus to allow him to make the final leap to accepting the truth of the texts.

But keep in mind that these stories are all present in a book that is itself deceptive. Even if the author of Barnabas was presenting the words that he thought Jesus would have said, he knew that he was not presenting an authentic history or reproducing the actual words of Barnabas. A forger is thus assuring his readers that even the most ostensibly authoritative texts have been contaminated, a warning that extended to scriptures. Almost certainly he saw himself in Nicodemus, reading out a story that he knew or suspected to be false but acting under a divine command. He is the distant heir of Micaiah, who speaks false words for heavenly purposes.

The focus on Nicodemus is central to understanding the book’s origin and purpose. As Christian Europe tore itself apart in religious wars, persecutions, and forced conversions during the 16th century, many thoughtful people were understandably reluctant to declare their views too openly. They accepted the official religious stances demanded by authority, even converting to the approved religious order as demanded, while retaining their inner reservations. Fiery orthodox believers like John Calvin angrily denounced such compromisers, such Nicodemites who retained their views in holy darkness. But a vast amount of modern scholarship has stressed the enormous significance of those who maintained their skepticism about religious authority, who even held growing doubts about the truth of scriptural claims, and who scorned intolerance and compulsion.

Those Nicodemites were also precursors of the Enlightenment that emerged a century later. And when that Enlightenment did emerge, one of the most influential and explosive texts on biblical scholarship was the Nazarenus, published by John Toland in 1718—which grew wholly out of his rediscovery of Barnabas. The Gospel of Barnabas rewrites so much of what we think we know about the development of Christian attitudes to faith and scripture.