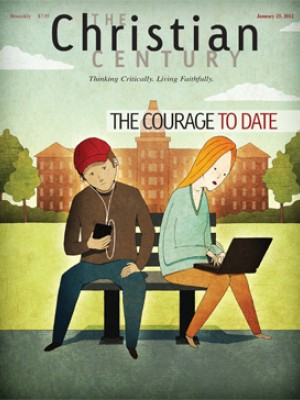

Courage to date: Kerry Cronin, relationship adviser

Read Stephanie Coontz's article on changing rules for sex and marriage

Read reports from college chaplains on campus sexual culture

Kerry Cronin has become known at Boston College as the "dating doctor," because of a talk she's developed on dating and relationships. Cronin offers students a specific script for dating. Trained as a philosopher, she is writing a doctoral dissertation on moral reasoning in higher education. She is associate director of the college's Lonergan Center, a fellow at BC's Center for Student Formation, and a teacher in the Perspectives Program, a interdisciplinary program in the natural sciences and the humanities.

How did the dating scene, or lack thereof, come into your field of vision?

I stumbled into it through conversations with students. About seven or eight years ago, I moderated a student panel on faith, and after the event the students and I talked about graduation and jobs and what they liked or didn't like about Boston College. Toward the end of the evening, I asked about relationships—were they seeing anyone? Did they feel like they had to break up before graduation or were they planning to date long distance? They looked at me as if I had been speaking Greek.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

All of these students were bright, intelligent and extroverted. These were not kids with no game. In another era, they would have been actively dating, but all of them reported that they had not dated at all while at the college. Several of them had never dated. I pressed them on the matter, and we started talking about the hookup culture. The more we talked about it, the more I detected both wistfulness and anxiety among the students over the thought of graduating without having developed the basic social courage to go on a date.

When you describe dating, you focus on relationships and downplay the issue of sex.

That's intentional. When my faculty friends and I first decided to give a talk on dating and relationships, we met for weeks ahead of time, trying to anticipate all the controversial questions that might come up. We thought, "They are going to ask us when they should have sex." When the Q&A period started, we were on pins and needles expecting difficult questions that might be pointed and controversial.

The questions we got were not of that kind at all. I'll never forget the girl who stood up and asked, "How would you ask someone out on a date?" I started to answer abstractly and philosophically. Holding a notebook, she stopped me and said, "No, what are the words?"

Another woman stood up and said, "You talk about sending signals, and I think I am sending signals all the time, but I have no idea if anyone can read them." A young man from across the auditorium said loudly, "We can't read them." It was a fun exchange in which students were speaking to each other about very practical things.

Another woman stood up and said, "You talk about sending signals, and I think I am sending signals all the time, but I have no idea if anyone can read them." A young man from across the auditorium said loudly, "We can't read them." It was a fun exchange in which students were speaking to each other about very practical things.

We know the statistics: students on college campuses are having sex. Some need help with decisions about that and some don't. But a larger majority needs help on basic social cues—which the culture doesn't give them.

The word normative is tricky, but students could use some scripts that can help them get through a fundamental life challenge: how do you tell someone you are interested in them without first getting sloppy drunk?

So your dating talk is less about sex and more about courage?

Absolutely. Students will ask for an appointment and wait weeks to talk to me. They want to know: "Is it OK to ask out someone I have been friends with for a long time?" "If I ask this person out, will he know that I have never kissed anybody before?" The questions are about courage, about making yourself vulnerable, about risky acts of relationship. They have very little to do with sexual decision making.

What is the appeal of the hookup culture?

First, we should note that the hookup culture is not necessarily about intercourse. Some students in that culture do have sex, but the majority do not. They are involved in a lot of making out. They don't see themselves necessarily as making sexual decisions.

At a basic level, the hookup culture scratches a biological itch. Students are building their sexual skill sets or trying to find out where they belong. They are trying out and testing their social powers. And some who are looking for relationships think that hooking up is how to get started.

Basically, the hookup culture is a shortcut to fitting in socially, to having social status. If you want to have a story to tell at weekend brunch where the stories are about who hooked up with whom, then hooking up is a way to do that. And feeling a part of something is an incredibly important part of college life.

By and large, students are not hooking up over the long term. Studies bear this out: students step in and out of the hookup scene. That scene is different for freshmen compared to seniors, for first-year women compared to first-year men, for first-semester sophomores compared to second-semester sophomores, many of whom are planning to go abroad for their junior year.

The ebb and flow into the hookup scene is largely motivated by a desire for a connection, but it is a desire that is hampered by a lack of courage. The difficult thing is having the simple courage to ask somebody if he or she would want to sit down for an hour and talk.

How did you start assigning dates as part of a classroom assignment?

After I started giving talks on dating, I was working with seniors in a one-credit class. The first semester we talked about all kinds of things: money, affluence, careers, social justice. I set aside one week to talk about relationships. Of the 14 seniors in the class, only one was dating someone. Another had previously dated someone while at college. The rest had not dated at all. So I said, "OK, why don't we try this? It's an assignment. Go on a date before the end of the semester." Though the students got all excited about it, weeks went by. They talked and talked about dating, but they never did date. Only one student was able to complete the assignment.

So the next semester I said, "You cannot pass the class without completing this assignment." The students needed more direction, and they needed a time frame. I gave them a written assignment and a list of 50 inexpensive places around Boston to go on a date. At this point I started offering definitions of Level 1, Level 2 and Level 3 dates. Students needed direction on how to go on a Level 1 date.

Why give people such specific scripts?

It isn't because I think that all first dates should go a certain way, but because the students were so lost. They felt safer the more direction I gave. When I said, somewhat tongue-in-cheek, "These are the rules, this is what you are going to do," they were very task-oriented. If I told them to follow through, they would do it. And they loved the results.

Some of the students said, "I am taking this class because you are going to make me go on a date. I can't bring myself to do it without the assignment." The class members really bonded, because it was a collective experience of courage and because they were doing something countercultural.

They would take the assignment back to their apartments and talk about it. The topic spread like wildfire. Students started stopping me to talk about it. Some wrote to me about it. Having students ask someone for a date by telling them that it was an assignment somehow took the edge off it. You have to make it light and fun. Students are not going to respond if you come down on them in a judgmental way.

What is a date?

Overall, the purpose of dating is to determine if you want to be in a relationship with someone. Dating at this first level is reconnaissance work only. You are trying to find out if you are really interested in and attracted to someone. To date someone, you have to focus.

Many students say, "I'd much rather find out about somebody in a group." But a group has a dynamic. Talking one-on-one with someone is a different animal. It is about focus: your attention is on someone else, and you are allowing someone else's attention to be on you—that makes you vulnerable.

At Boston College, there is a culture of niceness and friendliness. The students are good at easy, open-ended, loose social structures. Everybody is friendly and fun to be with. However, at night, once everybody is really trashed, it is a kind of a free-for-all. At night you can set aside that niceness and be aggressive in your assessment of someone's looks or sexual appeal. You can do things that your daytime self would never do. There is a disconnect between daytime and nighttime cultures.

That is why the kind of dating I am talking about is alcohol free. What the students use alcohol for does not lend itself to knowing who someone is. A date means that for at least one hour, I am going to focus on you. I am wondering if I am interested in you romantically and sexually.

How is this kind of dating different from or similar to a previous generation's view of dating?

In the second half of the 20th century, the script for dating was very concrete and somewhat rigid. I think there is a lot to criticize about it but also a lot to retrieve from it. It would be foolish to dismiss it, and it would be silly to try to live in that time and not in our own.

At its worst, any social script can be oppressive and overly rigid. But at its best, a social norm tells you what to expect. For example, when you go on a Level 1 date, you don't have to spend six hours and tell the person everything about yourself. You should be able to expect that you are not going to have to answer the question of whether you want to have sex. Instead, you will ask, say, how many siblings do they have and where did they grow up. If the script is an appropriate one, you will feel comfortable and feel that you can reveal the right amount about yourself. You will know not to discuss all your past failed relationships.

If we can retrieve from the old dating script a set of low-level expectations—for example, that it is OK to wonder about whether you would like to pursue something more with a person—that would be great. Some might think that this sounds overly programmatic, but the reason is because the script can ultimately give you more freedom.

I also tell students that with Level 1 dating, you get only three tries. If you are not interested in pursuing a relationship with someone, you need to find ways of letting it be known that you are not rejecting that individual as a person but just making an honest assessment of your feelings. I try to offer a way out of the intensity. Students tend to think that traditional dating is so serious. "Our parents and grandparents did that and got married when they were 20." Today's students don't want to get married at 20.

One of the things that really needs to change is that women need to be willing to ask men out. Lots of heterosexual students I talk to—especially women—say, "Oh no, I really believe that men should ask women out." I say to them, "That's total bullshit. You are a feminist in every respect except this one?" Both men and women need to be courageous. If you ask someone out, you should pay the expenses. It is a way of showing care and concern. That does not have to involve men showing some weird male dominance by footing the bill. It is about being human and taking responsibility for having asked.

Besides lack of courage, why do college students not date?

Both men and women are on serious career tracks. They have a certain level of affluence that they have attained or that they want and are very anxious about. They feel the need to spend their young adulthood getting the beginnings of that affluent life in place. They are hearing that it requires a career push and that relationships are distracting. They are not planning to get married until their mid-to-late twenties when their careers are under way. It is often the case that their own parents met in college and got married after college, and they are worried that they won't know how to meet someone by the time they hope to have such a relationship.

One of the stipulations that you put on this first date is that the students are not allowed to use texting to ask. Why is that?

I tell students that texting is the hookup of communication. Students will say that they love texting because they are constantly in touch. But I find that it keeps them also constantly confused because in texting you can't hear the tone of someone's voice. Texting has a lot of tacit rules. If someone sends you a very short text, you are supposed to reply only with the same number of characters. You have to wait a certain amount of time before replying. It keeps you guessing. It is not a great form of communication for what dating is about—which is communicating. Dating requires incarnate meanings—like seeing someone's face when you ask that person out. In most cases, you see their delight, and that will boost your courage.