On the fault line: Christian-Muslim encounters in Nigeria

The face of global Christianity isn't changing—it has changed. The average Christian is no longer a white American or European but a poor black woman in sub-Saharan Africa.

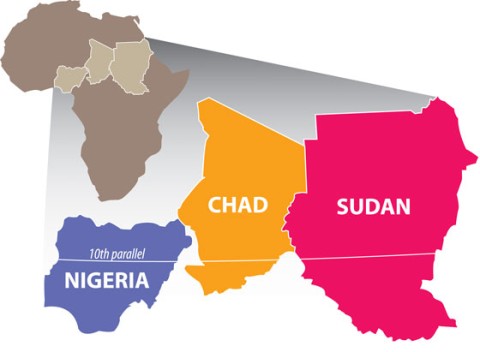

No single nation represents this shift in the face of global Christianity more powerfully than Nigeria. Home to 140 million people, it is Africa's most populous nation. Nearly half of its people are Christians. It is also a nation where Christians are often in conflict, sometimes violent conflict, with Muslims.

Pastor James Wuye is one of the finest Christian leaders I met in Nigeria. Graced with a warm chuckle and a preacher's gift for spinning stories, Pastor James—as he is known—is a vocal and charismatic evangelical leader. He lives and works in the northern Nigerian town of Kaduna (which means crocodile). Like Nigeria itself, Kaduna is almost evenly split between Christians and Muslims.