Inklings of good news

The Inklings will not go away. College courses devoted to this informal association of Christian authors based in Oxford in the 1930s and ’40s are oversubscribed. Their books sell millions yearly. Studies of their lives and works burden our bookshelves.

So why this tome? Among other reasons, because the proliferation of Inklings books is often prompted by Christian triumphalism. The Inklings are often regarded as having the last word on nearly every topic from apologetics to aesthetics, literary theory to literary history, allegory to fantasy and myth making. When questioned about important matters, enthusiasts tend to cite one of the Inklings as if nothing more need be said.

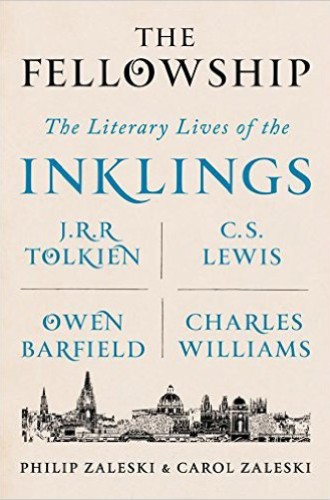

Carol and Philip Zaleski have something much more interesting to say. They provide a fresh, critical assessment of the four central figures—C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien, Charles Williams, Owen Barfield—and show how their writing lives were wondrously intertwined. In demonstrating the authors’ influence on one another as well as their continuing pertinence for our time, the Zaleskis take no shortcuts. They seem to have read nearly all of the books, ancient and modern, that decisively shaped the Inklings, and their narrative sparkles.