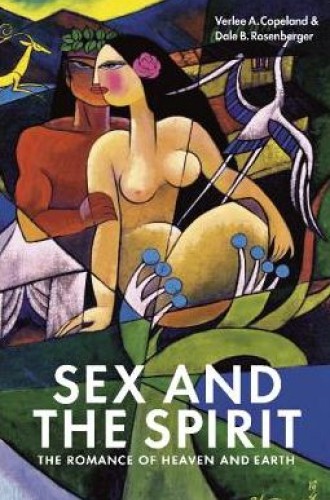

Sex and the Spirit,

by Verlee A. Copeland and

Dale B. Rosenberger

“Sex and the Altar” was the title our campus minister gave to a series on sexuality, hoping students might mistake it for a similar, more blasphemous phrase. (You have to be creative to get the attention of the 18–22 set.) It worked. The campus ministry house was full to bursting for those talks. In one session, two married clergy of differing orientations and races led a discussion about premarital sex. With passion and emotion, students discussed how to live a life in Christ while being in committed, sexually intimate relationships. After an hour or so, the clergy shared their beliefs, stating that they agreed with the position of our denomination: sex belongs only within the sanctity of marriage. Engaged discussion turned to silence, then anger and fear. One young woman broke down in tears. The students had made themselves vulnerable, and their church had shut the door in their faces. Later the two ministers recanted and explained that they’d wanted to show this contrast.

Mainline churches have struggled to express a theology, ethics, or spirituality of sexuality. The liberal church I attended while growing up was silent on the issue despite being quite vocal on many others. In my twenties I turned a few times to evangelical websites, looking for any kind of theology of singleness and sexuality that I could relate to.

Verlee Copeland and Dale Rosenberger seek to fill that mainline gap, countering both “society’s prevailing affirmation of sex as entertainment” and the “painful chasm between our spiritual and physical natures” in traditional church teaching.