God’s longing

The first time I read Micha Boyett’s Found, I didn’t know that I would be reviewing it. Which is to say I didn’t read the book with an eye for what potential readers might find in its pages, and I didn’t jot down critical notes in the margins. I read it for what I found in its pages. My marginalia were for myself, and my impressions were not yet bound to the obligations of a reviewer.

Perhaps, at least sometimes, it is acceptable to slip an uncritical reaction into a proper analysis of a book. This is mine: the morning after I stayed up too late finishing the last chapter, I called a local spiritual director to book my first appointment. For years I have resisted the whole enterprise, and this one imperfect yet powerful memoir nudged me to stop accepting the lukewarm state of my spiritual life. During my first session with Bridget I explained my mystifying impetus: I wanted to yearn for God as deeply as Micha Boyett does. For Micha Boyett longs for God with a disarming earnestness.

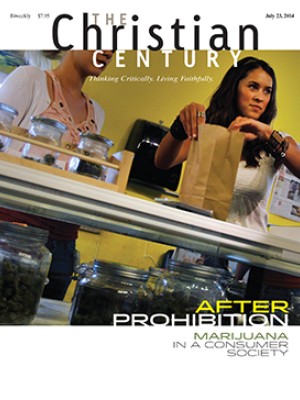

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Neither Boyett nor her story fit into tidy categories. Found isn’t a parenting memoir, though Boyett’s experience as a new mother no longer engaged in full-time ministry is the context for her so-called prayerlessness. Nor is this the tale of an angry former Southern Baptist repudiating her spiritual heritage. Her ambivalence for revival-fueled legalism is clear, but Boyett writes tenderly and appreciatively of her childhood church even as she grafts herself into a more liturgical expression of the Christian faith.

Although Boyett is drawn to monastic spirituality, Found is far from an account of wholesale immersion into Benedict’s Rule, for she does not so much embrace Benedictine practices as wrestle with them. At one point in the narrative, she is mildly annoyed by a well-meaning monk whose assessment of the relationship between her spiritual life and her maternal role rings false; at another point, she is moved to tears by the astute wisdom her brother’s friend shares at a charismatic prayer meeting. Her refusal to romanticize one tradition or vilify another is refreshing. She celebrates that which contributes wisdom and light to her spiritual reawakening, regardless of the source.

Although the writing is strong and frequently even exquisite (Boyett has a master of fine arts in poetry and isn’t afraid to write like it), there’s a certain messiness to the narrative, particularly as she strives to ground her spiritual journey in ordinary realities. A beautifully crafted paragraph sussing out the intricate details of her interior life might be rudely interrupted by her son’s need for a diaper change. She toggles between contemplating the resurrection and rolling out sugar cookies. Given Boyett’s gift for bearing witness to transcendence, the forays into more pedestrian moments are less satisfying.

Of course, people are amphibious, as C. S. Lewis famously put it, “half spirit and half animal,” and it is in the midst of the commonplace that Boyett encounters God. While Boyett prepares her house to host a dinner party for her husband’s colleagues, she is beset by feelings of inadequacy and insignificance. She tells herself, “This is all you do with your life. . . . Your husband works all day while you iron napkins in an adorable floral apron. You are nothing more than a housewife.” She continues:

Then, in the middle of that thought, I stop mopping. I prop the mop against the wall and look at my apron, which is absolutely as adorable as the lie in my brain said it was. . . . “Lord,” I say, “I am not ironing and mopping because I have nothing better to do. I am ironing and mopping because I get to take care of some people who deserve to be taken care of.” I sit there with my eyes closed, and I feel God’s nearness, the weight of the Spirit pressing in. I imagine God laying his hands on my head and pulling out the lie. His fingers pinch the gray cloud of a thought and then he throws it out. “Thank you,” I whisper.

Boyett writes just as evocatively about the times when she does not feel God’s nearness. Her doubts about God seem inextricably tangled up with her doubts about herself. One of the prevailing themes is her growing realization that she has to stop acting as though she must earn God’s grace. For a book that is very much about what one might do to nurture one’s spiritual life, perhaps the most appealing thing is that it really is about grace.

“We are all being written together by a generous Author,” she reflects. “My story is here in that bigger story, the story of a God who comes to the fainthearted, the bored, the bitter-spirited, the ones who cannot prove themselves worthy. I have spent so much life clutching tightly to the bitter spirit, keeping the gate of God’s grace closed tight. I have worked hard but denied myself the mystery of grace.”

The beauty of Found is that it isn’t about finding God; it’s about how God finds us. Maybe I didn’t make that monumental phone call because I longed to long for God the way Micha Boyett does. Maybe I drummed up the courage because Micha Boyett makes it seem entirely plausible that God is longing for me.