Eat with Joy, by Rachel Marie Stone

Conversations about food are moving in a startling number of directions. But no matter the disparate destinations, most emerge from the center point of dogma. From the calorie-counting nutritionism of church-based weight-loss groups, to the kale-chip raw foodism of vegans and foragers, to the fight-world-hunger leftoverism of thrifty Mennonites, sermonizing about food has become a cultural commonplace.

We know our sins so well: the obesity and diabetes epidemics, the wasteland of industrial food production, the pesticidal scrim on even locally picked strawberries, and the nutrition-coded inequalities that separate economic classes. Frankly, we’re ready for some fire and brimstone. We know that our globalized, industrialized, Monsanto-ized, commercialized, supersized food culture needs to be punished, purged and perhaps destroyed; nothing short of apocalyptic solutions will do.

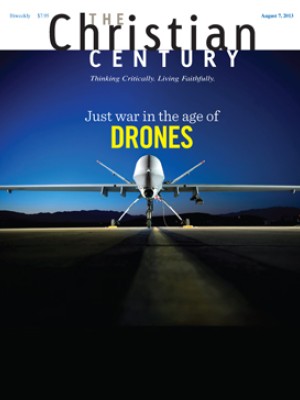

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Thus when Rachel Marie Stone offers homilies of food redemption rather than damnation, it may feel like a lovely if disorienting kind of grace. When we expect demands for penance, absolution can be disconcerting. Affirmation of the essential goodness of food and appetite, and the suggestion that it might be sacramental to eat Chinese food off of “planet-destroying Styrofoam in the church basement”—it’s enough to make people reread the book to make sure they haven’t missed out on the self-flagellation.

Stone doesn’t ignore the pathos of the starving masses, the awfulness of tomatoes sold in Minnesota in January or the bodily dangers of our cultural confusion about food. Nor does she ignore the multiple ways we are implicated in these things no matter how much we give to Bread for the World or how successfully we resist those addictive lime-flavored tortilla chips. In fact, she serves up all the horrid statistics you would need to weave a foodist hairshirt—the government subsidies on crops that are processed into ingredients for chips and soda, the mistreatment of farmworkers and meatpacking-plant employees, the hellish filth of concentrated animal feeding operations. She reminds us how few of us cook from scratch and eat together as families and how many of us struggle with obesity and its cousins, anorexia and bulimia.

But Stone always returns to the essential truth that food is a gift from God: “God’s sustaining love made edible.” She reminds us that no matter how far we are from achieving a foodist utopia, “moving redemptively toward joyful eating as best we can” might be good enough.

Each of Stone’s chapters gathers around a dimension of eating—generous eating, communal eating, creative eating and so on. Her reflections on eating in healing ways with an anorexic person, or building a food culture one meal at a time, or resisting agribusiness’s takedown of local foodways: these don’t feel as disparate or disconnected as they might appear at first glance. All of the topics find their home in the central theme of the book: learning to eat with joy.

Stone has come by her argument honestly. In the introduction she reveals that like many young American women, she spent years in an extremely unjoyful relationship with food. She struggled with what she calls “an unremarkable eating disorder . . . only slightly more dramatic than the eating disorder that most North Americans have: the psychotic notion that we can have it all, eat it all, do a minimum of physical labor and still look . . . thin to the point of undernourishment.” Conflicted religious and cultural messages—about gluttony, asceticism, thinness and appetite—drove her to the cardboard crumble of diet bars and a sense that food was inherently dangerous. She also experienced, at various junctures, an inability to eat joyfully because she was aware of global hunger and the unearned privilege of having access to an adequate supply of healthy food. By slowly recovering a sense that food is a gift from God, Stone found ways of eating generously, responsibly and in moderation, but without losing a joyful attentiveness and pleasure.

A substratum of biblical and theological earthworks fortifies Stone’s argument: that no matter how broken or polluted or alienated our food and eating practices have become, eating remains a great and God-blessed practice, one that should give us pleasure instead of guilt. Her refraction of scripture through the lens of food as gift is one of the greatest contributions of this slim volume. The Genesis account of Eden as an example of biodiversity, the story of Ruth as a narrative of food justice, the Bread of Heaven as more than a spiritual metaphor: some of these theological points are not new, but Stone makes them accessible without diminishing their depth.

Another gift of this book is Stone’s refusal to bow to food orthodoxy of any kind. Regarding the gift of eating communally, she writes, “Better the occasional meal shared with friends at McDonald’s than organic salad in bitter isolation.” She acknowledges that McDonald’s food “can’t speak clearly of God’s love and provision for creatures because of the many, many injustices involved at every stage of its production.” Of course, a meal home-cooked with ingredients from one’s garden speaks more lucidly of God’s provision than chicken nuggets and Diet Coke any day. But Stone doesn’t push us toward perfection. Instead, she nudges us toward greater faithfulness, suggesting that occasionally this might mean holding one food ideal more loosely than another.

Stone offers many suggestions, large and small, for drawing our food preparation and eating closer to the redemptive potential inherent in them: gardening, purchasing fair trade items, inviting people over for meals, joining a CSA, attuning ourselves to food insecurity issues. The chapters end with mealtime prayers, helpful points for action and recipes.

Although it’s increasingly common for publishers to add recipes to non-cookbooks to beef up their appeal, some readers might find their presence in this volume distracting. A book that moves from theologically graceful prose to a recipe for dilly cucumber salad may be trying a little too hard to be all things to all readers.

Even so, Stone’s astute volume will nurture readers in a way that few books about food and faith can, helping them to move beyond both the paralysis of food-related knowledge and the didacticism that sometimes accompanies food-justice activism. Eat with Joy carries its readers toward the comforting, joyful truth that God is a “loving parent, waiting to welcome us home with a hug and a bite of something to eat.”