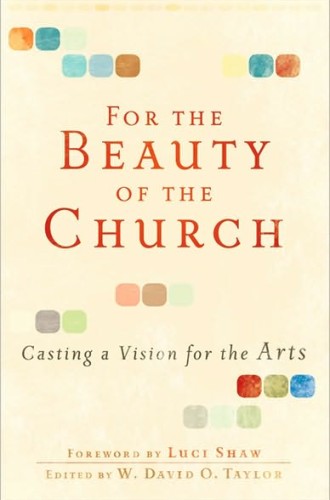

A review of For the Beauty of the Church

Too much writing about the arts and Christianity is apologetic, explaining why the church should be concerned about artistic expression. Within that category is a lot of writing that voices high-minded generalities about "good art" and "bad art" and about who should and should not be making art. This collection, which grew out of a conference on the church and the arts that was held in Austin, Texas, in 2008, has some of both types of writing. Happily, there are also some more constructive elements.

The essays are at their best when they explore the relationship between artists, pastors and the congregations in which they work. John D. Witvliet goes a long way toward clarifying how crafting artwork for corporate worship needn't involve dumbing down to the lowest common denominator but is instead a process in need of master artists who understand the purpose behind the Sunday gathering.

Eugene Peterson's essay is more memoir than instruction and accomplishes what good memoir can: without being didactic, it shows us how artists can shape a ministry. Joshua Banner highlights the importance of a pastor's intentionality in supporting artists, and Jeremy Begbie gives us a reading of Revelation that also speaks to the pastoral relationship to artists, but with much reflection on the movement of the Holy Spirit in creating "ever new" things. These three essays, with Witvliet's, are the heart of the book, making the volume easier to recommend to pastors than to artists.

The other essays in the book vary in quality and tone. Some are worthwhile without being particularly fresh. One is maddeningly narrow in its author's certainty about what constitutes good art, bad art and beauty in general.

One of the best features of this collection is the list of recommendations for further reading at the end of each essay. Many of the usual texts are cited (Walking on Water, by Madeleine L'Engle; Mystery and Manners, by Flannery O'Connor), but a number of more obscure books are listed to whet the appetite of a bibliophile interested in the topic.

The fact that this collection comes out of an evangelical context (though the word Protestant is used more often) should not scare off readers from other theological perspectives. Even when the contributors are speaking in theological terms, their emphasis is clearly on the arts and creativity, which manages to draw the discussion away from divisive doctrinal or dogmatic statements and allows for a discussion that can mostly be translated into broader ecclesiastical contexts.