The Hurt Locker

Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker is the best movie to come out of the war in Iraq so far. In fact, it’s the finest American war film of the past decade.

Bigelow (whose first movie was the vampire thriller Near Dark) and screenwriter Mark Boal underscore the uniquely terrifying elements of this particular war. Instead of portraying a squad of fighters whose disparate personalities suggest a cross-section of Americans—a convention of war films—the film focuses on three marines whose job is to find and defuse bombs. The set pieces aren’t battle sequences but potentially lethal conundrums for the “tech,” whose job is to dismantle the explosives while his two cohorts keep guard.

The film is built around half a dozen of these encounters, each a harrowing drama pitting the soldiers against invisible assailants. The only exception is a sequence in which the marines and a British unit are ambushed by snipers. The enemy is so difficult to see that the soldiers might as well be shooting at ghosts.

Bigelow rarely takes us out of the marines’ point of view, so we experience these unnervingly uncertain scenarios as they do. In the desert shoot-out, as a soldier complains that he can’t see his target, the image is so heat-misted that we feel we’re hallucinating. (The superb cinematographer is Barry Ackroyd.)

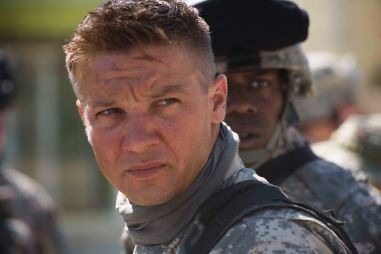

At the beginning the team consists of J. T. Sanborn (Anthony Mackie), the boyish Owen Eldridge (Brian Geraghty) and the tech, Matt Thompson (Guy Pearce), who has an easy, companionable rapport with both his comrades. But Thompson is killed in the opening sequence and replaced by William James (Jeremy Renner), a veteran of some 800 missions, who is both a daredevil and a loner. These qualities enrage Sanborn, who already resents the new tech, projecting onto him his anger at Thompson’s death.

The first time they go out together, James scatters smoke bombs on both sides of the road to deter locals from approaching the site. This makes San born furious because it cuts off his line of vision. Another time James comes across a nest of explosives in the trunk of a car and insists on remaining there for an agonizing period (just a few minutes, but it feels as if time has stopped) until he’s figured out how to defuse them, ignoring Sanborn’s order to abandon the site and leave it for the engineers to clean up. Eventually James literally stops listening to his team leader—he tosses aside his headset. Sanborn is so incensed that for a time he even fantasizes about killing the new tech.

The Hurt Locker isn’t morally complex. Bigelow and Boal never raise political issues; nor do they seem to have any philosophical interest in war. The issues are entirely psychological, and they reside in James. (Renner gives a fine, understated performance.)

Initially James is a mystery to the other members of his team, but he reveals himself slowly and subtly. He keeps remnants of the bombs he’s defused under his bed. What initially seems a morbid, even pathological trait turns out to be his way of dealing with his mortality: he sees the remnants as reminders of the things that nearly killed him. When Eldridge starts to fall apart during the ambush, freaked out by the task of clearing the blood that has jammed the weapon they’ve appropriated from a dead British soldier, it’s James who talks him through his attack of nerves by encouraging him to see himself as a competent soldier who can negotiate a tight spot.

James has a wife (Evangeline Lilly) and toddler at home, but he maintains an emotional distance from them. In one scene he calls her on his cell, then hangs up without speaking. He can’t reconcile his life in the war with his life at home. But he does form a surprising bond with a 12-year-old Iraqi boy.

The style of the movie is documentary realism, and Bigelow assembled the action sequences brilliantly. She also did excellent work with the ensemble, which includes Ralph Fiennes and David Morse in cameo roles.