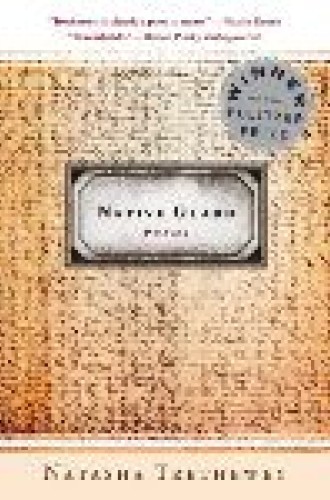

Native Guard

This collection, winner of the 2006 Pulitzer Prize for poetry, opens with “Theories of Time and Space,” a poem that alerts the reader to the territory under artistic surveillance. It begins with the lines: “You can get there from here, though / there’s no going home. / Everywhere you go will be somewhere / you’ve never been.” Memory and family history are the heart and soul of the poems, which are alive with the national history of America’s primary internal struggle against itself, the Civil War. Natasha Trethewey’s poems thread reflections of the poet’s life into the thick broadcloth of southern experience. Themes of race, of identity and belonging, of regional differences within the United States, and of the impact of the Civil War on an individual’s family experience run through the book.

Readers inclined to notice terms and concerns of the Christian faith woven into the cloth of a poet’s work will read in these pages how there is in Vicksburg “ground once hallowed by a web of caves; / they must have seemed like catacombs”; in the poem “Incident,” of a cross set up by the Klan on the front lawn, “trussed like a Christmas tree”; and in “Letter,” of the humiliating and disorienting ritual of Ash Wednesday, the crossing on the forehead recalled after a misspelled word is crossed out: “What was I saying? I had to cross the word out, / start again, explain what I know best.”

“What the Body Can Say” is a poem constructed near the intellectual territory of sacramental theology, where one simple thing may mean another very different thing. Christians are used to this complexity, as when bread is the body and water is a word. In this poem, two fingers held up mean in one moment victory, and in another, peace. A mother, on her death bed, opens her mouth to speak or to receive something, reminding the poet of Sunday morning mouths, above the altar, open for communion. She writes, “What matters is the context— / the side of the road, or that my mother wanted / something I still can’t name: what, kneeling, / my face behind my hands, I might ask of God.”

The poem “Graveyard Blues” locates the impulse for this poet’s work in the spirit of a familiar assembly: “When the preacher called out / I held up my hand. / When he called for a witness I raised my hand.” Many of the poems in this slim volume have a moral intensity and a memorial tone that must owe at least a little bit to the Sunday morning meetings that wade through memory and ring out calls for justice.