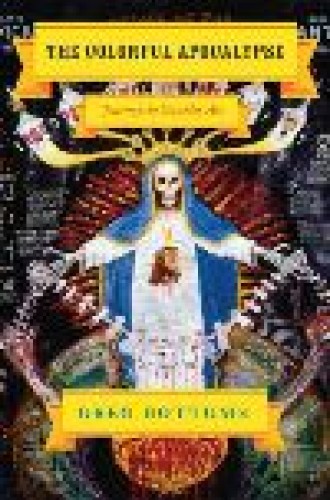

The Colorful Apocalypse

The Colorful Apocalypse is a poetic written documentary that can be read in one sitting. The outer layer of the book is Greg Bottoms’s portrait of three “outsider” artists: Howard Finster, William Thomas Thompson and Norbert Kox. These men are not quaint, folksy artists painting barns on old milk cans. Each is a biblical literalist; each has visions of the world’s end.

Bottoms’s main tool is the interview. Finster was dead before Bottoms visited Finster’s Paradise Gardens museum, but his daughter Beverly and several hangers-on were still around. Thompson was very much alive, and Bottoms had no trouble perching on the precarious balance between gallery staff who think Thompson a genius and friends and family who fear he might be crazy. Bottoms also spent considerable time with Kox, a former Outlaw biker gang member who has collaborated with Thompson.

The second layer of the book concerns Christian fundamentalism and these true-believing artists’ attempts to portray a purer vision of God’s message. Along the way we meet people like Mike, an earnest, younger artist “saved” by Howard Finster, and Robert, a large, bearded, overbearing adjunct art instructor who revels in the weirdness of hanging out with Kox. (I couldn’t help thinking of the guy who sells comic books in The Simpsons.) These folks are fundamentalists too, and they believe in a magical world full of immediate revelation, but they lack the manic obsession displayed by Finster, Thompson and Kox.

The third layer, about that mania, cuts closer to the bone. Bottoms ponders the possibility that these artists’ obsession is evidence of schizophrenia or something very close to it. This is neither pop psychology nor academic hypothesizing, neither romanticizing nor facile diagnosis. After all, Bottoms’s first book, Angelhead, is about his own brother’s schizophrenic “descent into madness.”

The concept of schizophrenia helps Bottoms show us how the artists seem to be experiencing the facts of the world differently from most of the rest of us. Whatever else they are doing, they are “shuffling” the “fragile facts” as they perceive them until they “form a straight line toward meaning.” The artists may understand the facts differently from you or me because of how their minds work, but the process of shuffling and line-making is universal. It is what Bottoms is doing in the book. It is what we all do when we construct meaning.

The beauty of this book is Bottoms’s steadfast refusal to reduce. He does not boil fundamentalism down to mental instability or neuroses, although he clearly notices those traits around literalism’s edges. He does not caricature the artists, and he resists the temptation to turn them into “noble savages.” The book realistically portrays its own “fragile facts” as something interpreted by an author who is intimate with art, mental illness and fundamentalism.

The Colorful Apocalypse rings true. I remember traveling with Scott Thumma and our families to visit Finster in the early 1990s. Finster played harmonica while our daughters danced. But when he talked to us adults, he was preaching into the ether. Finster was not pulling anyone’s leg. He had visions. And like Thompson and Kox, he was an obsessive producer—he created tens of thousands of pieces. His work did get commodified, but that doesn’t make his apprehension of the visions, or of God’s message to the world, any less real.

The Colorful Apocalypse is a portrait of a particular kind of human experience snapped by a photographer whose lens is intimately focused.