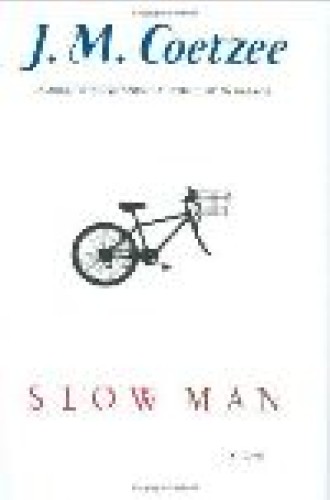

Slow Man/Philosophy Made Simple

How do two agnostic men—unsure of the existence of God and with no religious affiliation—deal with the coming of old age, disability and death? J. M. Coetzee and Robert Hellenga, both novelists with impressive track records (Coetzee received the 2003 Nobel Prize in literature, and Hellenga is the author of several highly acclaimed previous novels), fruitfully explore this terrain in their most recent books. Both deal with men in their fraught 60th year. A bicycle accident sends Paul Rayment, Coetzee’s protagonist, flying into a constricted life. In contrast, a series of impulses and visionary moments lead Rudy Harrington, Hellenga’s main character, into an expanded life. The two men couldn’t be more different, yet the similarities between their transitions into old age are striking.

Rayment, an Australian photographer, is a solitary man who never remarried after a childless union and early divorce. Harrington’s life has been focused on his wife, Helen, and their three daughters. The loss of his leg confines Rayment to his apartment and his neighborhood. Harrington’s wife’s death and his grown daughters’ independence propel him from Chicago to Texas, where he buys an avocado ranch. But for both men the longing for love and family is central, as is the struggle to understand and find meaning in the pattern of their lives. The comic, the absurd and the fantastic mark the year for them both. And both insist on continuing to have stories of their own, rather than giving in to the sensible patterns others want to impose on them.

Rayment’s brush with death, which forces him to put on the raiment of disability, propels him into an examination of his life, a life he finds frivolous and unproductive. He sums himself up as a person who has done neither significant harm nor significant good, who has slid through the world leaving no trace behind. “If none is left who will pronounce judgment on such a life, if the Great Judge of All has given up judging and withdrawn to pare his nails, then he will pronounce it himself: A wasted chance.” What troubles him most is that he has no children, that he has not achieved even the earthly immortality of passing on his life to a son. So in a sometimes darkly comic way, he sets out to get a son.

As he regains his health, Rayment falls in love with his nurse and caretaker, Marijana Jokic, a happily married Croatian immigrant with three children, and tries to adopt her whole family, especially her 16-year-old son, Drago. The inevitable complications are both comic and poignant. Though Rayment, who has an ironic mind, is well aware of his own absurdity, he is unable to stop himself. He sees himself as someone whose close encounter with death has left him haunted by the idea of doing good, a desire that he traces to his Catholic boyhood: “Jesus and his bleeding heart have never faded from memory, even though I have long since put the Church behind me,” he says. And he resists the suggestion that in his efforts to be the fairy godfather of the Jokic family, his own heart may not be entirely pure.

While Rayment sees his life as a failure because he has given so little nurture to others, Harrington has been a nurturer in a way most often practiced by women. He has found the meaning of life in his family, has cooked the family meals and has made life smooth for his career-minded wife, an art history professor at a Chicago college. Although his wife has been dead for seven years when his story begins, he thinks of her constantly. He tries, above all, to come to terms with her affair in Italy during the year she directed a student-abroad program, an affair that ended only when she learned she had cancer and came home to die. What had she discovered in Italy that she had not found at home? Had she been heroic in following the romantic adventure that gave her so much vitality and pleasure? Would she have come back to him had she not become ill? And can he, even at his age, still find love and something of the ecstasy his wife experienced in Italy?

Though neither novelist pays much mind to traditional religious notions of an afterlife, both suggest the possibility of alternative worlds. It seems extraordinarily difficult for anyone, with whatever doubts about God and the afterlife, to really believe that consciousness ends with death—that death is all. When the fantastical enters Rayment’s life in the form of an unexpected guest named Elizabeth Costello, a character from an earlier Coetzee novel, he posits an unusual life after death to account for her. Costello arrives at Rayment’s door claiming to have been sent and apparently knowing everything about him, including his thoughts, and she subsequently tries to direct his life. Is she writing him into a future novel? Or is he already one of her creations, real though he knows himself to be? Or, he asks himself, “Is this what it is like to be translated to what at present he can only call the other side?”

Rayment wonders if the “greatest of all secrets” has just been unveiled to him: “There is a second world that exists side by side with the first, unsuspected. One chugs along in the first for a certain length of time; then the angel of death arrives. . . . For an instant, for an aeon, time stops; one tumbles down a dark hole. Then, hey presto, one emerges into a second world identical with the first, where time resumes and the action proceeds . . . except that one now has Elizabeth Costello around one’s neck, or someone like her.” Costello remains a mystery, though her function as someone who helps Rayment understand himself and who proposes alternate futures to him is clear enough.

Harrington, who longs to remain connected to his wife, can’t accept that she is gone completely and forever. He posits an alternate universe in which she is, perhaps, continuing her life with her Italian lover, or in which the ways their lives might have gone, together or separately, are being acted out. When he is sleepless during his first night in Texas, he turns on the radio and listens to a Christian commentator predicting the imminent arrival of the Second Coming. A cradle Methodist who hasn’t been to church in 20 years, Harrington phones in with a message to his wife, telling her he loves her and asking her to call him.

In his attempt to experience his wife’s presence and to make sense of his life, Harrington turns to philosophy. He spends the year making his way through Philosophy Made Simple, a book one of his daughters has given him, and examining his own and his family members’ lives through the ideas of philosophers from Plato and Aristotle to Schopenhauer and Sartre. Religious views and practices come to him through the people he encounters: Catholicism through the Mexican farm workers who tend his avocado groves and the disgraced priest who becomes his friend; Hinduism through the Indian family of his daughter’s fiancé; and meditation through the holy man whose ashram is near his farm. Finally his eclectic efforts pay off. He achieves a mystical moment when his wife becomes fully alive to him again.

In this playful novel an elephant named Norma Jean who paints large, abstract pictures becomes part of Harrington’s new life. And he does experience the brief ecstasy of new love. But above all, this man who loves stories and who treasures the stories of his wife’s and his daughters’ lives becomes the central character in a story of his own.

Though Coetzee’s book has far fewer characters, it is the more complex of the two, and Rayment travels farther than Harrington on the road to self-understanding. Rayment struggles to hold on to his dignity even while he engages in the most undignified of actions—declaring his love to a woman who wants nothing of it and trying through ridiculous proposals to get the things he feels have been lacking in his life. Though Coetzee’s inclusion of Costello has been dismissed by critics as a postmodern trick, she becomes a complex and sympathetic character. She not only punctures Rayment’s self-deceptions and pretensions but suggests another way of dealing with age and disability: to accept, to adapt, to allow oneself to be ridiculous, to give up on “trying to hold all the beauty of the world in one’s arms” and to settle for affectionate companionship. Though ultimately it’s self-defeating to try to avoid yielding to the inevitable, it’s hard not to admire Rayment for refusing to settle into old age and disability.