Portrait of the artist

The satirical comedy Art School Confidential features Jerome Platz (Max Minghella) as a student at a prestigious Manhattan art college who discovers that it’s not the paradise he dreamed it would be. His classmates lack taste and imagination, his instructors are competitive and self-involved, and everyone is focused on the promise of a glitzy career rather than on education. Jerome himself gets caught up in these misplaced priorities.

It’s a tantalizing subject for a movie, and some of the details are quite funny, like the clumsy efforts of one classmate to construct an installation around himself. But the movie, collaboration between director Terry Zwigoff and graphic novelist–turned–screenwriter Daniel Clowes, has a wobbly tone and ends up shooting itself in the foot.

The problem may be Zwigoff’s inability to identify with Jerome. Zwigoff has a gift for getting into the point of view of outsiders and nonconformists. His first movie, the documentary Crumb, was a fascinating (and sometimes unsettling) look at the San Francisco comic-strip artist Robert Crumb, whose work embodied the late 1960s and early ’70s the way Peter Max’s posters epitomized the early ’60s. The film shows Crumb as the product of a wildly dysfunctional family.

Zwigoff’s first fiction feature and his first project with Clowes was Ghost World, about a quirky, sharp-witted teenage girl (Thora Birch) whose clashes with the conventional world are the stuff of deadpan comedy and poignant, even haunting, episodes in a difficult coming of age. Bad Santa, his next film, was a riotously profane farce that chronicled the unexpected salvation of an alcoholic petty crook (Billy Bob Thornton).

Zwigoff could be sympathetic to a misanthropic department-store Santa, but he doesn’t seem to have a clue how to depict an art-school freshman who just wants what everyone else wants—the respect of his teachers and the attentions of the prettiest girl in the school (Sophia Myles). Jerome winds up a cipher, and Minghella, who has shown some talent in other roles, is stranded without a character to play.

It’s unfortunate, because in the opening childhood scenes, where we see Jerome develop his talent for sketching as a way of getting back at the bullies who torment him at school, it seems as though this might be the perfect subject for Zwigoff: an outsider whose talent has the potential to make him the ultimate insider. Perhaps it’s that potential that makes it difficult for Zwigoff to develop much affection for his protagonist.

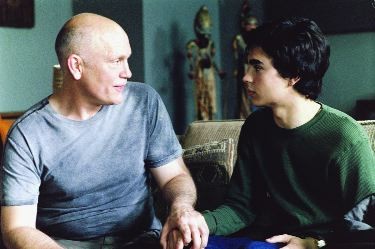

A sardonic classmate (Matt Keeslar) takes Jerome to meet one of the school’s alumni, a reclusive, talented artist (Jim Broadbent) who has become cynical and bitter. The artist’s wholesale condemnation of both his alma mater and the art world couldn’t mean much to Jerome, who’s 18 and eager; you’d expect him to shrug his shoulders and sneak out. Instead he sticks around and takes his host’s words as gospel. At that point the movie begins to fall apart.

A subplot involving a serial killer doesn’t help. And we don’t buy the success that another of Jerome’s classmates (Marshall Bell) has both in class—where his mediocre paintings unaccountably excite the other students and a professor (John Malkovich)—and out of it, where he courts the object of Jerome’s own romantic longing.

A savage satire of art school sounds like a good idea for a film, especially with Malkovich playing a teacher and Steve Buscemi as the proprietor of a local café (Malkovich and Buscemi are the best elements in the picture). But you have to find the right tone. Zwigoff and Clowes scramble for one, and in the meantime the film becomes ugly in a way they couldn’t have intended.

At one point Jerome carelessly causes a terrible tragedy, and the movie scarcely acknowledges what he’s done. As far as we know, Jerome has no remorse. He embraces notoriety for something worse that he didn’t do (commit murder), because it’s the key to a brilliant art-world career. That’s the movie’s punchline. It might even be funny if the filmmakers had not—apparently through oversight—made Jerome so morally vacuous that we no longer care what happens to him.