Further along

In Traveling Mercies Anne Lamott published the story of her slow slide into despair, and of the born-again moment that saved her. After years lost in addictive behavior, including bulimia, alcoholism, drug use and abusive relationships, she reached bottom. One day she lay in her room, sad and shaken after an abortion and too many drinks. “I became aware of someone with me. . . . I knew beyond any doubt that it was Jesus. I felt him as surely as I feel my dog lying nearby as I write this.” Lamott compared her acceptance of Jesus’ presence to acknowledging a stray cat who had followed her home and wouldn’t leave. “I quit,” she said to Jesus. “All right. You can come in.”

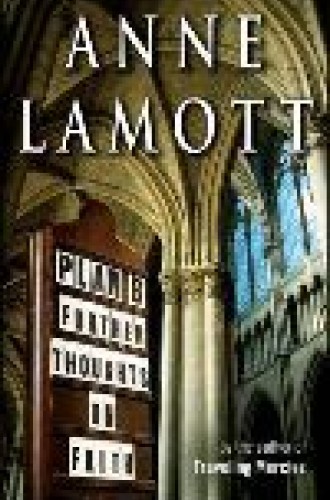

Few writers can stand on the edge of personal destruction and report on the process with both mordant wit and complete honesty, and the combination made the book a runaway best seller. Six years later, Lamott continues her account of her new faith and its application to her life as a writer, church member and parent in Plan B: Further Thoughts on Faith. With the help of her faith, Lamott seems to have gained strength to fight her addictions. She propels herself forward through rough moments by leaning on her congregation, her friendships and therapy, shaping a Christian life for herself and her son, Sam, now a teenager.

Her new essays, many of which have already been published by Salon magazine, will not disappoint those fans who want to read more about Lamott: the bittersweet account of her dog’s last days, her evolving relationship with Sam and a renewed relationship with Sam’s dad.

Some of these essays are worth noting for their vintage Lamott humor. In “Holy of Holies,” she starts out with “I did not mean to help start a Sunday school,” and the rest of the essay holds up to this ominous beginning. Lamott saw the need for a Sunday school at her church, and says that she felt “tugged” into the ministry. But she soon reconsidered:

It turned out that I did not like children, or at any rate, they made me extremely nervous. . . . I had imagined a wacky sort of rainbow love fest. I had not counted on so many minor injuries. For example, I had hoped we could throw around a beach ball while we memorized a line of Scripture—calling out one sentence, like “Come unto me, all ye who are weary and heavy-laden, and I will give you rest.” But the kids had the attention spans of fruit bats, and the boys would throw the ball too hard at one another, as if playing dodge ball. I quickly switched to “God is love,” but the children could barely remember that either, and wanted it to be their turn only so they could try to hurt the others with the beach ball. “God is love,” I said through clenched teeth, and then threw the ball to a girl, who froze, so that it slapped her in the face.

In “Adolescence,” Lamott steps back from grueling skirmishes with her son and describes the parent/teen tension as well as she did the parent/newborn struggles in Operating Instructions, her account of her first year with Sam. Her anecdotes merge the same biting wit with an undercurrent of persistent and crazy love for her son. Lamott gives the darker side of her 14-year-old son a name, Phil, and describes Phil as tense, sullen and contemptuous. At the same time, she admits, there is also a dark side to his 48-year-old menopausal mom, whom Lamott calls the Death Crone.

Some days were great, because Sam and I at these ages were wild and hilarious and utterly full of our best stuff; but other days, when Phil and the Death Crone dropped by, were awful. We sniggered impatiently, and sighed and gripped our foreheads, and we fought.

The story that follows this is a spare and elegant parable of family life with its regular stumblings into brokenness and irregular stumblings into moments of reconciliation. To be able to grasp both the beauty and the agony of parenting, especially as a single mom, is a rich gift, one that Lamott shares in several of these essays.

Other essays, however, repeat previously published material and depend too much on Lamott’s familiar tangents and quirks. Her preoccupation with her physical flaws, for example, was a revelation to readers of earlier essays but is no longer funny. In “Cruise Ship,” she tells us that “the aunties have put on weight since our last trip to the tropics, the aunties being the jiggly areas of my legs and butt that show when I put on a swimsuit. . . . Now they wanted to come with me to the Caribbean.” Enough limelight for the aunties.

And references to her abandoned addictions, however tongue in cheek, are just not funny six years later, especially in someone who takes her faith as seriously as Lamott does: “Usually he [her friend Tom] calls to report on the latest rumors of mental deterioration, drunkenness, or promiscuity, how sick it makes everyone to know that I am showing all my lady parts to the neighbors.”

Ditto Lamott’s preoccupation with the current administration. Even if the reader shares her views, the consistent moans and whines don’t wear well in book form. Granted, these were originally columns in Salon, where they may have worked well with a shorter shelf life. But in a book, Bush-bashing comes off as indulgence instead of insight.

Some of the essays are more inspiring. In these, the best of Anne Lamott, readers will welcome the writer who works her faith into every situation and comes up with pungent, irreverent and helpful truths like this one about our perpetual failure to listen for God’s voice:

I try to listen for God’s voice inside me, but my sense of discernment tends to be ever so slightly muddled. When God wants to get my attention, She clears Her throat a number of times, trying to get me to look up, or inward—and then if I don’t pay attention, she rolls Her eyes, makes a low growling sound, and starts kicking me under the table with Her foot.