Twisted childhood

When he wrote Oliver Twist in 1837, Charles Dickens had a cause: he was protesting the harsh and unjust treatment of children in England. His depiction of the situation was searing—more so than the best-known movie adaptations. David Lean’s atmospheric post–World War II film, which starred Alec Guinness, and the brilliantly stylized 1968 musical Oliver!, directed by Carol Reed, both played down the cruelty. (There have been many other versions: four appeared during the silent-movie era alone.)

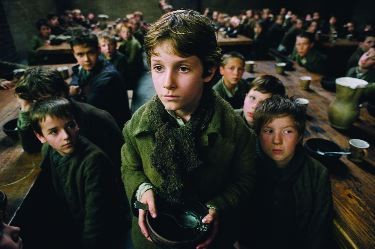

Roman Polanski’s magnificent Oliver Twist, with a script by Ronald Harwood, is in some ways the most faithful to the book. Polanski and Harwood are the first filmmakers to include the episode in which Oliver (Barney Clark), ejected from the workhouse after asking for an unprecedented second helping of gruel, narrowly escapes being indentured to a sadistic chimney sweep, who cackles as he describes how fire can wake up a sleeping boy in a chimney—if the smoke doesn’t smother him first. They’re also the first to dramatize the sickening way in which all the adults in downtown London seem to get swept up in the punishment of an apparently wayward child.

When Oliver is chased through the streets for stealing a handkerchief— though in fact it was lifted by two other boys, young thieves he’s found lodging with at the home of the fence Fagin (Ben Kingsley)—he’s stopped by a workman who flattens him with his fist. The man then brags to the owner of the handkerchief, the benevolent Mr. Brownlow (Edward Hardwicke), that he’s responsible for bringing the young reprobate to justice.

These are the details you’d expect Polanski to seize on. He’s never been squeamish about portraying cruelty. No one has ever given so graphic an account of the Macduff murders in Macbeth as he did in his 1971 film of the play. That scene was about the slaughter of innocents (including children), and in his Oliver Twist you can feel, behind the story of one lucky lad who found advocates—not just Brownlow but also Nancy (Leanne Rowe), the friend of the housebreaker Bill Sikes (Jamie Foreman)—the ghosts of thousands who did not.

Polanski is a deeply compassionate filmmaker, but not a sentimental one, as his last film, the Holocaust drama The Pianist, showed. He omits the Victorian melodramatic structure of Dickens’s book, with its surprise revelations about Oliver’s true identity. He includes, in only slighted altered form, the farewell exchange between Oliver and Fagin in prison the night before Fagin is to be executed. The boy expresses his gratitude for the kindness the old crook showed him when he might have been left to starve in the streets. The movie doesn’t romanticize Fagin as the musical did: he’s a corrupter of children, and he’s implicated in Sikes’s scheme to murder the boy when a robbery falls through and he’s recognized. But Fagin is among the few grown-ups ever to show Oliver pity, and Oliver’s acknowledgment of what he owes the old man is as horrifying an indictment of his society as any episode in the picture.

This Oliver Twist is a prestigious piece of work all around: beautifully designed, lit and scored, with an almost flawless ensemble—mostly of British character actors whose faces you may not recognize. With deceptive ease, they find the balance between comic caricature and naturalism that Dickens calls for. It’s a darkly funny movie—and that’s Polanski’s specialty.

Young Barney Clark isn’t quite good enough to pull off the emotional challenges of the role of Oliver, but he’s visually right: his face has traces of intelligence and refinement in it. Nancy is shockingly young (she seems about 18)—a choice that underscores Polanski’s theme—but Leanne Rowe doesn’t make enough of an impression. Everyone else does, even those in small parts, like Jeremy Swift as the beadle, Mr. Bumble, and Mark Strong, with pre-Raphaelite hair and rotting teeth, as Sikes’s confederate Toby Crackit.

As Fagin, Kingsley is about as good as you can imagine. The filmmakers have removed any verbal references to the character’s Jewishness, which is a smart decision. Dickens’s portrayal of Fagin reflected the prejudices of his culture; they would be glaringly anti-Semitic in a 21st-century dramatization. Polanski allows audiences to connect directly with Kingsley’s superlative performance, with its physical and vocal inventiveness, comic mastery and hints of melancholy and paranoia. In the 1948 version, Alec Guinness’s Fagin was the embodiment of the great legacy of English character acting. Kingsley carries on the legacy.