Choices of Youth

The extraordinary six-hour Italian movie The Best of Youth is like a long novel. By the end you feel you know the characters the way you know your own family and circle of friends. The setting is the social and political turbulance of the years between 1966 and 2003. The writers, Sandro Petraglia and Stefano Rulli, and the director, Marco Tullio Giordana, approach public events with an intimate lens. Considering the length of the picture (generally shown in two three-hour screenings) and of the period it portrays, the film has a surprisingly compact cast of characters. Though the narrative sometimes leaps ahead several years and regularly stretches back and forth across the country—and occasionally steps outside it—the film brings to mind a story by Chekhov more than a novel by Tolstoy.

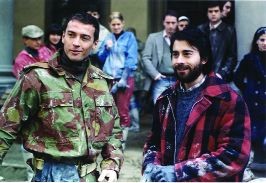

The protagonists are two Roman brothers, Matteo (Alessio Boni) and Nicola Carati (Luigi Lo Cascio), college-age sons of a successful merchant and an elementary-school teacher. They’ve promised themselves a trip abroad with friends as a prize for surviving their final exams. But at his oral exam in Italian literature, Matteo, restless and brooding and prone to unexplained outbursts of anger, senses condescension from his professor and stalks out of the room, throwing away his university career. He and Nicola split up, and their lives take dramatically different turns.

Nicola has an archetypal 1960s experience in Norway, where he falls in with some hippies and lives for a while with a Norwegian woman. Matteo joins the army, as if seeking some official outlet for his anger and also punishing himself by choosing a life unsuited to him in every way. The brothers’ paths don’t cross again until both wind up in Florence in the wake of a flood—Nicola as a volunteer in relief work and Matteo as part of his army unit. That’s also where Nicola meets Giulia (Sonia Bergamasco), who enchants him by uncovering a piano, unloaded with other furniture in the crowded street, and playing Ravel. It’s a magical, romantic, when-the-world-was-young moment.

Nicola follows her back to Turin and moves in with her. They live activist lives while he studies to become a psychiatrist, devoting himself to more open-ended—and open-hearted—ideas about how to heal the psychically sick. The brothers meet again in Turin when Matteo, now a cop, is one of the reinforcements called in to put down the student revolutionaries. And they meet again in Milan, where Matteo takes a post at a police precinct and Nicola is working to close down old-fashioned, abusive mental wards.

The Best of Youth is about how people’s lives are shaped by the struggles of their time. Nicola and Giulia represent the best of their generation, shaken to their roots, committed to looking beyond themselves to the needs of others. But Giulia’s political commitment, in combination with her driven, melancholic personality, wrecks her life and nearly wrecks Nicola’s.

The real contrast in the story is not between Nicola and Matteo but between Matteo and Giulia. She detests those in power and abjures the thought of compromise; his in-the-trenches experience has taught him to hate leftists. We can’t support either point of view. As the movie goes on, both fling themselves away from the people who love them and into their private hells. Matteo is estranged from his family, while Giulia gets more and more involved in the revolution until she walks out on Nicola and their daughter and joins the Red Brigades, where she’s trained as an assassin.

Nicola loses them both and blames himself. His brother and his lover represent the limitations of his healing powers. Those powers work on Giorgia (Jasmine Trinca), a young psychiatric patient he restores to life, and on the young people he ends up working with, but the dreadful irony of the film is that the two people he loves the most are beyond his help.

The film is a powerful emotional experience. It’s also beautifully acted. Scenes from it may come back to you for years, like the one in which, after his death, Matteo’s mother (Adriana Asti), peering into the apartment he’s never let her see, comments wonderingly at the quantity of books and then hurls them away as if they were somehow responsible for his fate, having kept him behind a wall that she couldn’t pierce. The movie is brilliant on family relationships and the intellectual camaraderie of youth. It’s both shattering and inspiriting.