Looking for love

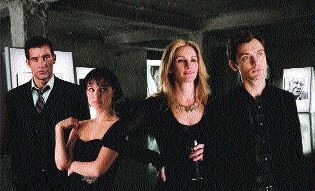

Purporting to deliver the straight goods on modern sexual interactions, Closer is glossier than last summer’s similarly themed We Don’t Live Here Anymore, and it has a more impressive pedigree—an award-winning director (Mike Nichols), a highly acclaimed British stage play (by Patrick Marber) for its source, and a glamorous cast: Julia Roberts, Clive Owen, Jude Law and Natalie Portman. It has Oscar nominations written all over it. But it contains barely a convincing moment.

Roberts plays an American photographer living in London who shoots the book-jacket picture for Law’s first novel; he makes a play for her, but when she learns he has a live-in girl friend (Portman), she resists her attraction to him. She winds up with Owen’s character instead, but the night her gallery show opens, she and the novelist initiate an affair that eventually devastates both their households. (In We Don’t Live Here Anymore, the two couples swap partners.)

Films like these operate by a kind of emotional extortion: if you don’t accept their vision of the world, they say, then you must be afraid to confront hard realities. But it’s hard to buy the premises of this narrative. Law meets Owen in a sex chat room on the Internet. Pretending to be a woman—and using Roberts’s name—he arranges an assignation in the London Aquarium, a locale Roberts frequents to find subjects for her photos. The movie never explains why Law is posing as a woman in a chat room, and there is no reason for him to set up this beautiful woman he’s just been entranced by.

The film has American Beauty–style plotting, devising flashy but implausible twists that, under scrutiny, turn out to be just excuses for the next plot turn. In American Beauty, there was no reason to believe that the Kevin Spacey character would get a job at a fast-food joint or work out naked in his garage, but if he didn’t do the first, he wouldn’t see his wife drive by with her lover, and if he didn’t do the second, the closeted gay marine next door couldn’t spy on him. In Closer, if Owen weren’t under the misapprehension that he’d been targeted by Roberts for an afternoon of anonymous sex, then he wouldn’t try to hook up with her at the aquarium, and they wouldn’t be married six months later.

The shocking details—the comfortable exec who goes to work at a Burger King, the chat-room ruse—are supposed to signal that the movies are in tune with the subterranean rhythms of contemporary life. The woebegone tone of Closer, like the satirical tone of American Beauty, is meant to alert us to the authenticity and pointedness of its statement. In Closer the statement amounts to this: life in the big city in the 21st is lonely and intimacy is difficult, so people look for love in all the wrong places. That’s all there is to get out of Marber’s script, which specializes in brittle, epigrammatic exchanges and harsh truth-telling in behind-closed-doors battles.

There aren’t any human beings inside the fancy theatrical dialogue. The movie feels like a barely adapted stage play, with sudden jolts of action where the original scenes must have ended and no attempt to explain what happened in the spaces between them. Why on earth, to pick a glaring example, does Roberts wind up marrying a man who mistakes her for the kind of woman who hangs around the aquarium looking for pick-ups?

Given this framework, Roberts’s ability to suggest a flesh-and-blood woman and make us sympathetic to her character’s romantic plight is a considerable achievement. Owen is the most technically accomplished of the quartet of actors, but all we can do is admire him, since there’s no way to make an emotional connection to his character.

At the beginning of his phenomenally successful four-decade career as a director, Nichols made Carnal Knowledge (1971), an ugly, hollow picture about the sexual lives of two buddies from college days onwards that was taken very seriously as a comment on the way we live. Closer is Carnal Knowledge redux. In its most objectionable scene, after their two relationships have broken up, Owen wanders into a strip club and finds Portman working there, so he buys her services as a private dancer and tries to get her to sleep with him. The movie sells us the high-end yet sterile milieu, Portman’s seedy job and Owen’s vengefulness as proof of its downbeat honesty. In 1971 the critic Pauline Kael wrote of Carnal Knowledge that it’s “like a neon sign spelling out the soullessness of neon.” Nichols still hasn’t taken down that sign.