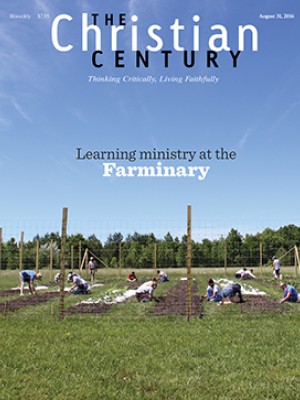

Cultivating ministers: Farminary students get their hands dirty

Princeton Theological Seminary's farm grows food. But this isn't the main point.

The students’ assignment was to spend half an hour walking around the farm and observing things. They could inspect the pond and grassy spaces. They could look into the hoop house, where lettuce, spinach, kale, onions, parsnips, and carrots had sprouted. They could search for nests and cocoons in the trees and bushes, which were still wet from a heavy rain. The aim was to take the time to notice parts of the 21-acre farm they might otherwise overlook. It was an exercise in paying attention.

When the students reconvened, one of them showed the professor, Nathan Stucky, a photo she had taken. What was this cluster of spheres covered with red spikes, wondered Lindsay Clark. Was it something made by an insect? (Clark later looked it up and found that it was a fungus that affects apples and cedars.)

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

In small groups, the students shared what they had seen on their excursions. The information they gleaned was not as important as the experience of slowing down and just looking, without having to worry about being productive. The discussion ran to the importance of recognizing the value in what is, rather than focusing on a result, whether a crop yield or a test score. Stucky posed a question: “What if the role of the teacher is to help people become fully themselves?”

The discussion was part of a class at Princeton Theological Seminary called Scripture and Food. It took place on a spread of seminary-owned land that is home to a program dubbed the Farminary. The Farminary is the locus of an innovative project in theological education. Though food is grown at the farm, that’s only part of happens there, and it’s not the main point.

“The motivation here is the vitality of the church,” said Stucky, who is director of the Farminary.

“We don’t have this Farminary so that we can make a bunch of farmers. The point is a particular kind of formation for people who can go out and lead in churches and lead in the world.” Stucky hopes the Farminary will help students learn about relationships, about the embodied nature of ministry, and about life and death.

“I’m suspicious of education and formation that does not take into account our best understanding of what it means to be human,” he said. “We are embodied, social, relational, always-hungry-for-transcendence creatures. And our theological education, more so than any other education, should account for that. The farm helps us do that in a way that isn’t opposed to the traditional classroom, but that might bring what happens in the classroom to life.”

Princeton is not the only seminary engaged in sustainable agriculture. Many schools are partnering with congregations to address issues of food and justice. And Princeton isn’t the only theological school that owns a farm. But it may be the first to create a theological curriculum in the context of a farm with the aim of shaping students for ministry.

Kenda Creasy Dean, professor of youth, church, and culture at the seminary and a member of the Farminary steering committee, sees the Farminary serving as a corrective of sorts. “Theological formation got co-opted by industrial models of education,” she said. Dean described how in the early 20th-century Sunday school classes began reforming themselves to resemble public schools, which trained students the way factories trained workers. Teachers separated students into age groups, sat them down in chairs, and expected them to listen to the teacher.

“We inadvertently adopted a system designed for something very different than discipleship,” she said. “If you’re cultivating love—which is what discipleship boils down to—you’re cultivating relationships.” The traditional method of teaching focuses on giving the right answer and getting good grades, which fosters a sense of competition and fear of failure—all of which runs counter to the skills needed to form Christian community.

As Stucky puts it, “Innovation, creativity, successful farming, successful ministry—all depend on the ability to take risk, to endure failure, and to move on.”

On the day I visited the Scripture and Food class, students spent six hours at the Farminary, alternating the time between discussion and physical activity. After the assignment on paying attention, the students turned to farmwork. Some planted seeds in trays, preparing to cultivate broccoli, radishes, and eggplants. Others watered plants in the hoop house. And some uprooted a cover crop and put the plants into the compost pile.

The course aims to teach students about agrarian thought and practice, and the reading list includes several selections from the works of Wendell Berry. But Stucky also wants students to think about how the practice of working the land might lead to insights for ministry and for teaching the faith. He wants students to think about how food is consumed, but also how scripture is consumed—and how the two activities might be related.

The students gathered later in the barn, where they ate a potluck meal from food they had prepared themselves: soup, quinoa, watermelon. After the plates were cleared, they talked about their final projects. Each student had been asked to come up with an educational plan for a congregation that built on the food and scripture biography of that congregation.

The discussions were in some ways like any seminary class, but the students seemed more at ease with each other and their teacher. They laughed more. They were less focused on proving they had done the readings—though they did infuse their reflections with references to themes in the assigned texts for the day, which included the story of manna in the wilderness in Exodus 16, a chapter from Norman Wirzba’s Food and Faith, and Marge Piercy’s poem “To be of use.”

The discussions, the shared physical tasks of the farm, and the shared meals create a closeness among the students, said Clark, who had brought her specialty, a banoffee pie—banana and toffee—to the potluck. “This class has a bond that we just don’t see in other classes.”

Princeton bought the land that is now used by the Farminary in 2010 simply as a way of diversifying its financial holdings, said Craig Barnes, Princeton’s president. A few years later, when students were talking about sustainable agriculture and providing food for hungry people in Trenton, New Jersey, some faculty members and students raised the idea of the seminary purchasing a farm. Barnes looked into the matter and found out the seminary already owned one.

“All of these things were swirling around at the same time,” he said. “It seemed like a Holy Ghost thing.”

Barnes sees the Farminary as tapping into a desire for seminaries to have a voice on matters of public concern. “A lot of administrators like me are yearning to demonstrate the social relevancy of theological education,” Barnes said. “Very few people are saying, ‘Where are the theologians on this issue?’ But they used to, back in the Reinhold Niebuhr days.”

Such hopes and visions for the role of the seminary take place in the midst of a changing landscape for theological education. At Princeton, that reflection has included a desire to make the most of the fact that the seminary is rooted in a par-ticular spot on the earth.

“Our connection to the land is not incidental, it’s actually core to our identity as human beings,” said Jacqueline Lapsley, associate professor of Old Testament, who is also on the steering committee. Lapsley pointed to the work of Bible scholar Ellen Davis of Duke Divinity School, who has stressed that much of the Hebrew Bible is rooted in agricultural life. “This is relentlessly agrarian literature,” Lapsley said.

Lapsley has cotaught a class at the Farminary on Hebrew Bible texts and interpretations. Students in the class read texts, worked on the farm, and discussed how their farm experience affected their view of the texts and how the texts affected their view of the farm.

She recalled a day that she had spent planting carrot seeds with the students. She thought about the reading from Genesis 2:15, which says that God put human beings in the garden to serve and preserve it. The word that’s usually translated as till can also be translated as serve, she noted. She thought about what it means to serve the ground—how it requires sweat and holds the possibility of failure.

“The garden embodies everything we do in ministry, ” she said. “All of that was just incredibly concrete.”

Lapsley is encouraging other Princeton professors to consider coteaching a course with Stucky at the farm. She finds Princeton faculty enthused about the Farminary. Meanwhile, some other scholars have worried that the Farminary courses will lack academic rigor. But, said Lapsley, “it’s false to equate rigor with abstract theologizing.”

The emphasis on the land has also elicited some worries that the Farminary is somehow encouraging ecopaganism. Serving and preserving the ground does not mean worshiping it, Lapsley said. “A core piece of our vocation is to serve this earth so that it might be fruitful for everything that lives here,” she said.

Dean also sees tending the soil as part of the Christian calling. Churches are recognizing this, as is evident in congregations’ growing interest in gardening and sustainable farming. But congregations still need to learn how to describe what they’re doing that’s different from the rest of the world.

“Young people and young adults are just hurtling toward the American success narrative,” Dean said. “It’s just killing our young people.” Teenagers attend SAT prep classes instead of youth groups, and churches struggle to tell a story that’s different from that of the wider culture.

“I see the agricultural rhythms as standing over and against the consumerist patterns that dominate our culture,” Dean said.

Classes at the Farminary strive to teach students how to create communities where people care for each other the way that gardeners tend a garden, nurturing life in places that appear inert.

“It’s easy to lose sight of the fact that ministry traffics in life and death,” Dean said. “If, at the end of the day, ministry is about anything less, we’re wasting our time.”

Knowing the rhythms of life and death is crucial not only because pastors will be ministering to the dying and performing funerals, but because they may well end up ministering to congregations that are closing their doors. “Probably a lot of us will be called to take over dying churches,” said student Chris McNabb.

And in many congregations, people are dealing with death daily. Veronica Cotto Santa thinks of the youths she has known in Puerto Rico, who risk death for money and power. “By preaching only life, as we often do in our churches, are we teaching false religion?” she wondered. “We need to be aware that what we’re preaching is worth living for and worth dying for.”

Working with other students on a section of the farm, Jean Wilkinson, a clinical psychologist who serves as an elder in a congregation made up predominantly of Latino and Latina immigrants, reflected on how the image of a seed contains life and death. Sometimes parts of us have to die in order to make way for new ways of living, he said.

Wilkinson said he thinks about humans in their environments like plants in the soil. “You can’t expect everything to grow the way you thought it would,” he said.

That is true for the Farminary itself, which is still testing its curriculum. Stucky said he has become more aware in the courses he’s taught that issues of race have to be addressed.

“I am recognizing as I familiarize myself with the agricultural story of the church, the country, and world that those stories cannot be separated from the race story,” Stucky said. “Our food system has always depended upon the marginalization and exploitation of people of color.” One text Stucky has added to the syllabus is James Cone’s essay “Whose Earth Is It Anyway?” which connects racism to the degradation of the earth.

Some people who hear about the Farminary think it is a Christian version of the trendy interest in local artisan food and in agrarian life. “We certainly have students who come with their romantic ideals about what our life on the land might look like,” Stucky acknowledged. And the Farminary is interested in addressing issues of sustainability. One late-spring evening the farm hosted leaders from congregations that either have a garden or are thinking about starting a garden. And this September the Farminary will host its second Just Food conference focused on issues of food justice, sustainable agriculture, food insecurity, and the profound ways people relate to food.

Through actions as simple as eating, “we’re all tied to the land,” Stucky said. “Are we aware of that? And then, from the particularity of the Christian tradition, are we aware of the theological perspectives that have been around for centuries and that have proclaimed that the connection between humans and humus literally leads us back to the Creator?”

“Feminists and marginalized peoples, as well as neuroscience, have been saying for some time that there are embodied ways of knowing,” Stucky said. “It’s actually really important that our intestines be involved in the educational process, that we wouldn’t just cognitively make sense of things, but that it would descend into our guts and we would feel it.”

The farm creates ways for seminarians to come face to face with death in a classroom setting through thinning seedlings or while tearing up a winter cover crop and adding it to the compost pile. At the same time, students also see resurrection, such as in how the decomposition of some plants yields fertility for others.

“To be an eater is to be a being dependent on death,” Stucky said, “whether it’s the carrot that we eat or the chicken that we eat.”

The lives of the farmer, the land, the carrot, are all given so the others can flourish. Rather than getting bogged down in morbidity, Stucky hopes students will learn a greater reverence for all of life.

“Those sensitivities can all be nurtured at the farm in a way that students feel it in their intestines,” he said.