Two young fighters speak as Israelis and Lebanese mark ten years since war

(The Christian Science Monitor) Since the brutal 34-day war between Israel and Lebanon’s militant Hezbollah organization, which ended ten years ago on August 14, the border has enjoyed near-unprecedented calm.

Neither Israel nor Hezbollah seeks another war, both being wary that the scale of the next conflict could be far greater than in 2006.

But if war should break out, two potential adversaries are Abbas, a 24-year-old Shi’ite from southern Beirut, a member of Hezbollah who has been fighting in Syria’s civil war, and Elazar Symon, also 24, a Jerusalem native and a reservist in the Israeli army who saw action in the 2014 war in Gaza.

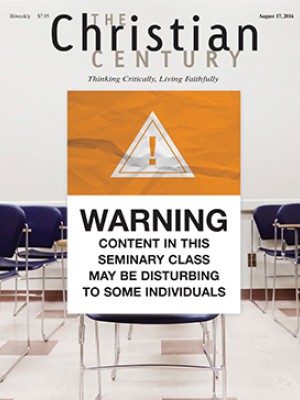

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

They also share a deep faith in their respective religions and have undertaken religious studies: Symon taught by rabbis in a West Bank settlement yeshiva and Abbas by Hezbollah clerics in a Beirut classroom.

Abbas, who asked that his last name not be used as he was not authorized to speak to the press, views Israel as “an illegal entity that occupies Arab land and commits massacres” and must be confronted. He is willing to embrace martyrdom for the cause, believing that the act of self-sacrifice serves as a paramount demonstration of faith in God.

Symon, on the other hand, regards Hezbollah as a “terror organization that wants to banish me from my country.”

In September 2011, Symon joined the Israeli army’s hesder track, a five-year program combining rigorous religious studies and military service, typically in combat units. His yeshiva was in Otniel, a small settlement south of Hebron in the West Bank. An agreement between the Israeli military and some 70 hesder yeshivas across Israel arranges for 1,500 students annually to be conscripted to “religious only” units.

In December 2002, two Palestinian militants stormed the Otniel yeshiva and shot dead four students and wounded seven others. Teachers and a manager from the school have been killed in similar attacks over the past decade.

But Symon said the violence has not spoiled the humanistic Judaism he was taught at Otniel.

“There was never an atmosphere of revenge,” he said. “To me, the world isn’t divided into Jews and Arabs, but into gentle people who want to be nice, and others who are rough and evil.”

In a small home in southern Beirut, 170 miles north of Otniel, sits Abbas, a builder by profession. He grew up with Hezbollah, watching the party’s Al-Manar television channel, listening to the speeches of its leaders, and supporting friends and relatives who joined the organization.

Abbas joined the party almost a year ago amid the war in neighboring Syria where Hezbollah has dispatched thousands of fighters to help protect the regime of Syrian president Bashar al-Assad and battle extremist groups like the self-described Islamic State and al-Qaeda’s Jabhat al-Nusra.

“We have the ideology of Ahl al-Bayt,” he said, referring to the Prophet Muhammad’s family line through Imam Ali that is followed by Shi’ites. “In our belief, our enemies are Israel and the Takfiris.” Takfiri is a term used to describe extremist Sunnis, such as members of IS, who view as apostates all those who do not follow their strict interpretation of Islam.

In Abbas’s religious studies, Hezbollah clerics taught him the principles of Iran’s theocratic system, which Hezbollah follows, and Islamic texts, according to their interpretation.

Then he underwent a 45-day training program at a camp in the Bekaa Valley in eastern Lebanon as one of around 50 new recruits, all Shi’ites, from various parts of the country.

Symon’s military service began in 2013 when he was drafted into the Israeli army’s Nahal infantry brigade. That was followed by eight months of basic training in the Negev desert. At the peak of the toughest week of training, Symon motivated his friends as they lay among the dry thorns of the desert. He said that their suffering could be compared to a sacrifice to God: “Historically, if my property were a cow, I would have sacrificed that. Now, my action is lying here in the thorns for a week. If that is what I have to give, that is what I give.”

In July 2014, Symon, now a sergeant, defended a unit inside Gaza that was exposing an attack tunnel leading into Israeli territory. Once, at an abandoned home his unit had occupied outside Gaza, Symon noticed one of his subordinates firing at a water tank atop a pile of debris.

“I came and asked him why he’d shot at that,” Symon said. “I told him: ‘When the owner returns at some point, he’ll find his entire home in ruins and hate us anyway. Not that it makes much difference, but this water tank survived. Why destroy it too?’ The soldier was a good guy and took my point. He said he hadn’t thought about it.”

Even during the Gaza war, Symon and his fellow religious soldiers observed the sabbath.

“Shabbat is a real ray of light, a salvation,” he said. “I have no idea how a soldier can get through the army without shabbat. It seems like a nightmare.”

While Symon’s wartime service ended, Abbas’s battlefield experiences continue. He has served five tours so far in Syria. Abbas admits he was frightened the first time in combat, much of it consisting of infantry assaults with barely 50 yards separating him from his enemy.

Hezbollah built its martial reputation on fighting Israel, first resisting the Jewish state’s 18-year occupation of southern Lebanon and then fighting it to a standstill in 2006. But Hezbollah’s intervention in Syria dwarfs any of its earlier wars with Israel. It has fought nonstop for about four years and has lost in excess of 1,200 people, compared with about 1,500 in wars with Israel between 1982 and 2006.

Abbas and other committed Hezbollah fighters believe that Israel and the West are backing the effort to unseat al-Assad in order to weaken the regional alliance between Hezbollah, Iran, and Syria.

“The Takfiris and the Israelis are brothers; they are a group together,” Abbas said. “When I am fighting in Syria, I feel as though I am fighting Israel.”

While the Syrian war has taken a toll on Hezbollah in terms of casualties and growing war fatigue among supporters, a generation of Hezbollah fighters has gained combat experience in the bloodiest conflict in the world.

“The more times I go to Syria, the better I become as a fighter,” Abbas said.

Abbas knows that he could be killed in Syria, but it would be “an honor to become a martyr,” he said. “We are fighting to the end, and when it is over we will wait until the next war.”

This article was edited on August 1, 2016.