Who matters to us?

When NBC news anchor John Chancellor retired in 1993, a reporter asked him what was the most memorable moment in his 43 years of reporting. Chancellor didn’t mention Vietnam, or Watergate, or the Kennedy assassinations. Instead he began to describe an experience from the 1964 Republican National Convention.

Not surprisingly, black delegates were scarce on the convention floor that year—the nominee was Barry Goldwater, who was opposed to the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The few black Republicans who were present were anti-Goldwater. Chancellor recalled stumbling upon an older African-American man toward the back of the assembly hall who was holding on to a pillar. The man was weeping. Chancellor could hear the man mumbling beneath tearful heaves, “All my life . . . all my life.” At first the newsman and his aide thought the man had fallen. But when they leaned in closer, Chancellor saw that the man’s sport coat was riddled with cigarette burn holes.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

A racist delegate had decided that this man would be his personal ashtray and, adding further insult and cruelty, other delegates had joined him. “The pain and anguish on that man’s face is something I will go to the grave remembering,” said Chancellor. In four-plus decades of reporting, it was this image of one black man’s face that endured.

Athlete-turned-activist Jackie Robinson was on hand for the convention and heard racial epithets hurled from various southern white delegates. He said, “I now believe I know how it felt to be a Jew in Hitler’s Germany.”

The power to empathize with the feelings of people whose lives do not match our own is supposed to be a uniquely human experience. Armadillos and grasshoppers do not have this capacity. We humans do. Moral concern usually begins when one person makes an effort to place himself inside the shoes of another person, aiming to become, in some measure, one with the other.

Privilege, ease, or perceived self-superiority impede this oneness, especially when the life of the other is understood to be of less value. Those with the most social power often tune out those with less social power. Those who overestimate their own wonderfulness are particularly susceptible to disregarding the value and dignity of certain others.

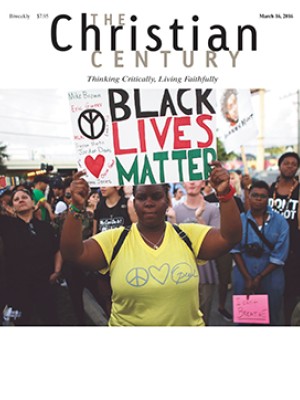

We’ve come a long way toward righting some racial wrongs in the last 50 years. But as leaders in the Black Lives Matter movement will attest, our nation has much further to go. Elsewhere in this issue ("Black Lives Matter"), Reggie Williams quotes Coretta Scott King: “Freedom is never really won. You earn it and win it in every generation.” So it seems.

A young African-American attorney in my town used to commute on weekends between his Chicago law school and his girlfriend’s house in predominantly white McHenry County, Illinois. He is justifiably angry that officers pulled him over 17 times in a two-year period, each time without cause. He knows the enduring truth of Coretta’s words.

What drives the Black Lives Matter movement above everything else? It could be that all-too-common experience of many black people who live with the same anguish John Chancellor heard in the words he took to the grave: “All my life . . . all my life.”