March 24, Maundy Thursday: Exodus 12:1-4, (5-10), 11-14; John 13:1-17, 31b-35

Slaughtering animals, washing feet—I can smell the rooms in both Exodus and John.

As a teenager, I worked as a locker room attendant at a country club. The job paid handsomely, but only if you were willing to shine shoes—thousands of shoes. It wasn’t degrading—the old, usually white, men didn’t call me “boy” or anything—but it was menial. I’d shine their dress shoes while they golfed and clean their cleats while they got dressed. When there were job openings in the locker room I’d try to get my friends hired, which usually ended with them quitting within a week or two.

This was when I started to glean that people like jobs but don’t necessarily like to work.

Later, as a student at Morehouse College, I preached my first sermon. People came from out of town to support me, and a respectable chunk of the campus was abuzz to hear this freshman who had the nerve to preach. The sermon started well enough but soon turned into an unfocused, overlong, flimsy, self-important diatribe. Afterward the dean of King Chapel informed me that I would not be preaching again for quite some time. In his words: I had some listening to do.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

He was right. I wanted to preach, but I didn’t want to do the work—the work of preparing a sermon, of considering other perspectives, or of relating to other people. I wanted to be their teacher. I wanted them to wash my feet, not the other way around.

Both the Passover reading from Exodus and the foot-washing text from John contain images that are visceral and intensely physical. Slaughtering animals, handling blood, and eating organs; disrobing and kneeling and washing feet—I can smell both sets of activities. Both narratives suggest the value of doing things—of the work itself, not just the paycheck.

Passover celebrates what God has done, how the people have been blessed and served. This is a theme in the John text as well, as Jesus serves the disciples and insists that they allow themselves to be served. But the point he stresses is the one that follows: that we are to serve others, and that it is in this work of service that the blessing comes. “If you know these things,” says Jesus, “you are blessed if you do them.”

Christians like blessings. That word has stampeded American Christianity to the point where many expect to be blessed tangibly as a result of their faith, and those who have less are deemed less faithful. It is almost as if those who do hard work are seen as cursed or less fortunate. Let’s be honest: we tend to see people who work long hours as the poor exception to our privilege, even though the word privilege itself indicates that it’s not the norm. Our ancestors who worked in factories—or on plantations—often have their stories told in ways that present them as pitiful.

Yet Jesus says the blessing is in doing the hard work. In the culture of the church, we tend to vaunt our intellectuals. In some contexts a high value is placed on deconstructing theology and changing hearts and minds, but even these are mostly intellectual exercises. And there persists a gap between blue-collar and white-collar descriptions of ministry. Ministers who protest, who get arrested for standing on the front lines for workers’ rights or against police corruption—such people are often seen as somehow lower than an eloquent Ph.D.

The foot washing in John 13 is not a thought exercise. Jesus actually kneels down and washes the disciples’ feet—and then tells them to do likewise. It isn’t proverbial; it is service. Maundy Thursday is an opportunity to ask how we can add service to our lives and again live in the call to wash the feet of others. It’s an opportunity to ask how we can live our faith in more than symbolic terms.

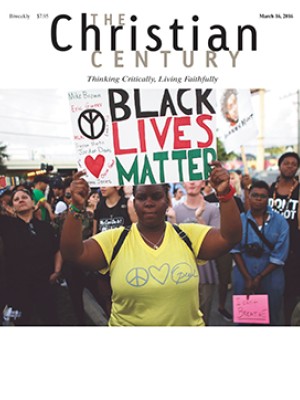

Most of all, this moment at the end of Jesus’ ministry reminds us that an embodied faith must include the physical world—the world of physical bodies and their sights and smells. Our bodies must be part of our core commitment to God. And when we are bereft of things and unable to use our bodies, we are still pressed to ask how our commitment to Christ breathes in our physical world. To take just one example, it’s one thing to say that black lives matter and another to add our physical presence at the next action. Such acts are where the blessing lies.

Words are important, too. In some communities, even saying something like “black lives matter” out loud can be a bold action that carries risk. There is value in verbal acknowledgment. Our society moves too fast to pause and acknowledge the many faces and voices that are often hidden and marginalized, and these scriptures don’t affirm that kind of silence.

What they do is to caution us against the seduction to be on the receiving end of glory. When we serve others, we give glory to the God who rescued the Israelites from Egypt. Foot washing is an example of memory come alive, a needed reminder of what genuine Christ-following looks like. It’s worth asking whether we have been waiting to have our feet washed or the other way around.