December 20, Fourth Sunday of Advent

I once read Luke 1 on a park bench during a jazz festival in Burlington, Vermont. I was practicing what homiletics scholar Chuck Campbell calls “dislocated exegesis”: the art of reading scripture in an unusual physical location, to see what this allows the reader to discover in a familiar text. As a woman sang in French on a nearby stage, I thought about Mary. We know that Mary is virginal, and she prays a lot, and she talks to angels. But I had the thought that maybe she’s also a jazz singer. Maybe Mary is in heaven right now, sipping martinis with Ella Fitzgerald and teaching the angels how to scat.

Jazz has never been my favorite kind of music, and I don’t know much about it. When I got home from Burlington, I read up on it. I learned that jazz resists definition. It involves syncopation and saxophones and the occasional trombone. Jazz is sometimes high-stepping, cakewalking ragtime and sometimes jazz has a frantic Dixieland beat and sometimes there is bebop.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

One thing that you can almost always find in jazz, even if there is no bebop and no saxophone, is improvisation. A musician takes what she knows of scales and modes and the melodic theme and creates something new—in response to what the other members of the band are doing, or even in response to some random ambient noise. (In 2001, back when cell phones were still sort of new, Wynton Marsalis took a ringtone that had interrupted his performance and magically improvised around it until it resolved into the song he’d been playing, “I Don’t Stand a Ghost of a Chance with You.”)

The word improvise comes from the Latin for “not foreseen.” Surely Mary did not foresee that one day while she was home, calmly practicing her scales, an angel would show up, announcing that Mary is pregnant with a baby whose father is God and who will be the savior of the world. But while hard for Mary to foresee, pregnancy that is a gift from God also is not without precedent. And as Mary figures out how to respond to God’s action, she latches onto the precedent of Hannah.

Like Mary, Hannah responds to the gift-pregnancy God gives her by singing. “My heart exults in the Lord,” she sings. “My strength is exalted in my God.” Hannah praises God: “There is no Holy One like the Lord.” And then she sings about the God of Israel taking pleasure in capsizing the social order. The Lord “raises up the poor from the dust,” Hannah sings. “He lifts the needy from the ash heap, to make them sit with princes.”

Perhaps a song about ash heaps is not the obvious thing to sing when you learn that you’re pregnant. But Hannah isn’t making up her song on the spot, either. She is drawing on a yet older song, the song Miriam sings after the Israelites cross the Red Sea and the powerful Egyptians drown behind them. Miriam’s song gives Hannah’s song its basic pattern: declare God’s triumph, taking care to note God’s penchant for defying the hierarchies of the world. Hannah sings a variation on Miriam’s song—and years later, when Mary needs to say something about a strange action of God that will change her life and the life of the world, she takes the motifs of Miriam’s song and Hannah’s and she puts them together and swings.

Like Hannah, Mary first describes herself overflowing with praise: “My soul magnifies the Lord, and my spirit rejoices in God my Savior.” Like Hannah, Mary declares God’s holiness. And then like Hannah, Mary devotes most of her lyrics to God’s habit of taking down the powerful and enthroning the oppressed. Mary knows Hannah’s song, and she improvises.

The church, perhaps, should do likewise. When I came home from the jazz festival, I read Sam Wells’s Improvisation and Robert Gelinas’s Finding the Groove. Wells and Gelinas each point out that the life of faith requires improvisation—and this seems especially true in the context of the current American church landscape, which is a landscape of change. Some things in the church work just as they worked a century ago, just as they’ve always worked; others are not working now. The love of God is working just as it always has, but maybe the Every Member Canvass is not.

In response to these changes, the thing to do is not to despair; nor is it to invent from whole cloth. The thing to do, rather, is to invent from the chords we have. Pianist Frank Barrett says that “the best jazz is always on the verge of falling apart.” This is true of churches, too. The best church is always on the verge of falling apart—and life with God has always involved making new combinations from the essential practices of our faith.

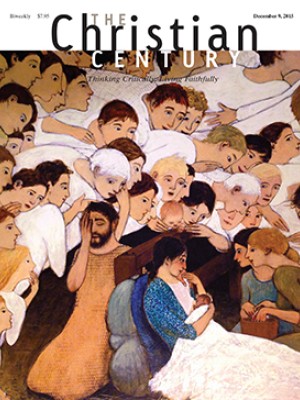

And so, in this moment of awaiting the one in whom all our hopes are vested, I picture Mary as a jazz singer. I picture her in a smoky club, with a five-piece band behind her. She is wearing a beaded dress—blue beads, with sequins.

She’s scatting and she’s swinging. The clarinet has just picked up the countermelody, someone has just dimmed the lights, and the night is still young.