Sunday, July 13, 2014: Matthew 13:1-9, 18-23

Jesus' parable presents not differences between people but different kinds of terrain within each of us.

Does the divine expression, the word, really work? Does it make a difference in our lives and in the world?

My yearning for the difference-making word drew me to James Crockett’s work in the Rogers Park neighborhood of Chicago. James spent eight years in prison for crimes he committed as a gang member. But the word, so he tells it, reached him in prison. James read words of God’s love and sacrifice, and he was overcome with emotion and a sense of clarity. James knew he was to dedicate his life to sharing this love with other hungry and weary souls.

Now free, James devotes his life to “real talk” with young men about reforming from the wayward ways of gang life. He teaches them the word of righteousness, a ministry James calls “C247,” or “Christ 24/7.” James is now known in the neighborhood for walking up to young men on street corners and asking them, “Hey, man, what do you know about the Jesus piece?”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

James’s courageous conversations have produced a weekly Bible study consisting of about 30 recovering gang members seeking to get right with God, family, and community. A recent study of Matthew 5:38–45 occurred in the context of murders at the hands of a rival gang. Feelings of anger, frustration, and despair were stirred together with Jesus’ teachings about turning the other cheek and loving your enemies. In a holy moment, I heard some of the most powerful sermons I’ve ever heard about how we are created for greatness and not violence, how the cycle of violence can stop with us, how the great kingdom that lies ahead for all can begin here. Sometimes the word makes all the difference in the world.

Other times it doesn’t. While encounters with the word regularly inspire and move people, many of us can also remain wounded, anxious, and resigned—and most of our undivine habits, customs, and systems continue along untransformed. Clarence Jordan once said that “proof of the resurrection is a church on fire.” Most churches, however, steadily simmer along.

After worship one Sunday, a parishioner named Harold said to a group of us, “We need to close every worship service with a community-wide conversation in which we ask, ‘What are we gonna do about what God said he wants today?’” This was one of the best ideas ever produced at the church I serve. It never took off. Harold reminded us, though, that we have to take care of where we let the word fall, to make sure there’s room for it to take root in our lives.

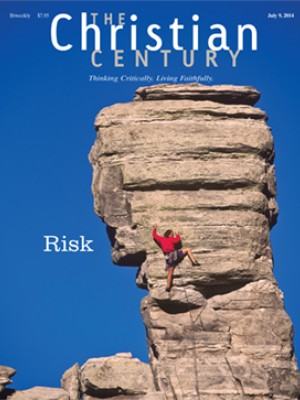

Jesus’ parable of the sower and his interpretation of it offer insight into how the divine expression does or does not gain life in the world. Jesus begins with a sower who sows seeds extravagantly rather than meticulously, scattering them over all kinds of terrain. The terrain determines the seeds’ fate. There are many risks: being consumed, lacking resources, drying up, getting choked. Only those that fall on good, deep soil result in life unleashed in bountiful quantity. The word makes a difference, but it needs fertile ground.

Jesus later relates the sowing of seeds on varying kinds of ground with spreading the word to different “ones.” The hearing of the word must be met with understanding and joy, free from the distracting cares of the world. When the right conditions are met, and the person who hears the word understands it, receives it joyfully and responds freely, the word bears fruit and yields a bountiful harvest. This parable gives preachers an opportunity to remind a congregation of when the word worked just right, to reflect on how and why.

The parable carries layers of meaning, though, and invites layers of reflection. The lectionary leaves out the material between the parable and its interpretation (verses 10–17), but it’s important. It draws a distinction between the disciples, to whom the secrets of the kingdom of heaven have been given, and others to whom Jesus speaks in parables. Those who are not insiders are given layered metaphors that require work and discernment in order to extract meaning.

Perhaps accepting the simple interpretation of the parable leads us too readily to presume to be insiders, to be already in possession of the kingdom’s secrets. When parables seem straightforward and comfortable, there’s usually more there. Jesus says he speaks in parables for those who do not understand so that “I would heal them.” He goes on to remind the disciples that “many prophets and righteous people longed to see what you see, but did not see it, and to hear what you hear, but did not hear it.”

What they see and hear differently is Jesus, the embodied Word before them, the one come to reveal God’s healing will and proclaim repentance, “for the kingdom of heaven has come near” (4:17). Those who see are those following Jesus, who will in so doing discover the parts of themselves that fall short and deny and avoid and fear.

So in its deeper layers, the parable presents not differences between people but different kinds of terrain within each of us. Those who see are those who stand before Jesus and know that we all contain such variety. In my good moments, the word can fall on fertile ground and grow up. At other moments, the word lives a short life. Maybe our work is to cultivate our inner grounds, to extract the rocks and thorns of busyness and distraction, so that God’s word can work on and through us.

The word works, but only sometimes. We have to take care of who and how we are, so that the word has a fertile place to fall.