McWages

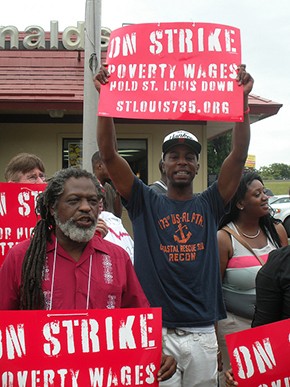

In recent weeks, downtown crowds have seen something unusual at lunchtime: fast-food workers on strike. In city centers across the U.S., thousands have participated in daylong actions. While most labor strikes these days aim only to mitigate ongoing losses, the fast-food workers have a more ambitious demand. They think they deserve $15 an hour, more than twice what some of them currently make.

They’re right. If it looks like the strikers are overreaching, that’s just because they’re so woefully underpaid now.

It’s not like fast-food chains—which are highly profitable—can’t afford to pay a little better. The problem is that the chains can’t afford to raise wages on their own, because that would give a competitive edge to the place down the street. Hence the response by workers of an industry-wide strike.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Fast-food workers, however, aren’t unionized; they don’t have traditional collective bargaining power. And while this campaign is significantly funded by the Service Employees International Union, there’s little chance that McDonald’s and Taco Bell will become SEIU shops. Private-sector unions are in steep decline, and fast food’s quick turnover rate makes it an especially difficult sector to organize.

But there’s another actor that can change the entire industry at once: government. This seems to be the fast-food campaign’s real goal—not voluntary action by the employers, and not unionized workplaces, but a higher minimum wage law.

The federal minimum wage is currently $7.25—in real dollars, almost a third lower than it was at its peak in 1968. A minority of states offer a little more; Washington State is the most generous at $9.19. That’s not enough. Workers deserve a living wage, which in some places is even more than the $15 the fast-food workers are demanding. People shouldn’t have to work multiple jobs in order to have their basic needs met.

A wage increase for the working poor would also be good for the rest of us. It would take some pressure off beleaguered social welfare programs, by which taxpayers now in effect subsidize employers by providing the services that keep their low-wage employees housed and fed. And there’s no better way to stimulate the economy and create jobs than by putting more money in low-income pockets.

Would higher wages also cause layoffs? Perhaps, but not many. Most of the low-wage American jobs that can be outsourced already have been, leaving mostly service jobs, which have to be done here. Some forward-thinking employers, such as Costco, have voluntarily paid service employees more—and benefited from the employee loyalty and stability this creates. But the norm, in the fast-food industry and elsewhere, is to pay service workers as little as possible.

Most service workers can’t count on their employers to pay them enough to get by. With unions declining, the government is the last defense. It’s past time for a much higher minimum wage.