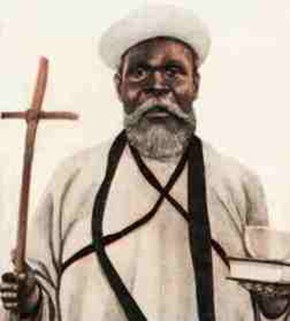

Church of William Harris

This year marks the centennial of an explosive episode in modern Christian history. In July 1913, a prophetic evangelist named William Wadé Harris began his march across the French colony of Ivory Coast, calling people to live purely and to reject pagan religion. The astonishing impact he achieved suggests the deep popular thirst for his words and for the distinctly African style in which he clothed it. Some observers claimed he won 100,000 converts within a few months—until panicked French authorities drove him out of the country. Although prophets abounded in 20th-century Africa, Harris’s sweeping religious revolution marked the beginning of a critical new phase of mass evangelization.

Harris’s name is familiar enough in the story of Christian Africa, and Mark Noll and others have listed him among the century’s most significant Christian figures. His life repays study for what it tells us about his mission’s appeal. It also reminds us of a horrendous, and largely forgotten, aspect of the Western Christian encounter with Africa.

Born in 1860, Harris came from the Grebo people of Liberia—a context critical to understanding him. Anyone interested in antebellum American history knows the debate over whether freed slaves should be resettled in Africa and how that idea led to the creation of the colony of Liberia in 1822. Few nonspecialists, though, know how grimly that scheme worked out.