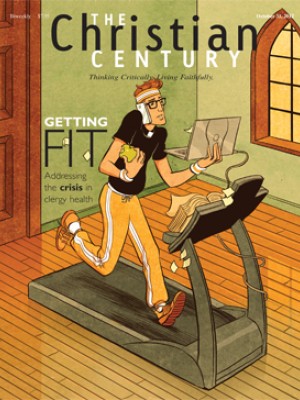

Fit for ministry: Addressing the crisis in clergy health

Being a pastor is bad for your health. Pastors have little time for exercise. They often eat meals in the car or at potluck dinners not known for their fresh green salads. The demands on their time are unpredictable and never ending, and their days involve an enormous amount of emotional investment and energy. Family time is intruded upon. When a pastor announces a vacation, the congregation frowns. Pastors tend to move too frequently to maintain relationships with doctors who might hold them accountable for their health. The profession discourages them from making close friends. All of this translates, studies show, into clergy having higher than normal rates of obesity, arthritis, depression, heart problems, high blood pressure, diabetes and stress.

But research also says that pastors’ lives are rich in spiritual vitality and meaning. Pastors say that they have a profound calling and are willing to sacrifice to fulfill it.

Is there a way for pastors to be both physically and spiritually healthy? What would enable clergy to become physically healthier? What effect does physical health have on spiritual well-being, if any? The Clergy Health Initiative is trying to find out the answers to these questions. Funded by the Duke Endowment, the CHI is the largest and most comprehensive effort ever made to study clergy health and to improve it.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The program focuses on United Methodist clergy in North Carolina who sign up for a two-year program. At the beginning of the program and at several intervals, participants are screened extensively to measure both their wellness and their perceptions of their wellness. They take part in a program for healthy eating and wellness called Spirited Life and consult monthly with a wellness advocate—a person trained to help clergy make and achieve health goals. They also receive small grants to fund projects related to wellness, such as a gym membership or a vacation.

Over 1,100 clergy are enrolled in Spirited Life. The first group enrolled in January 2011 and will finish at the end of 2012. The second group began in 2012 and will finish at the end of 2013. A third group will begin in January 2013.

Head researcher Rae Jean Proeschold-Bell said the program has shown early signs that it can help clergy lose weight and improve their health according to five metabolic indicators.

But the CHI wants to do more than improve metabolic scores. It wants to shift the culture in which clergy live and work, and it wants to develop a way of thinking and acting in regard to health that is specific to the pastoral vocation.

When Proeschold-Bell first began to study clergy health, she gave pastors a survey that measures perceptions of health. It asked questions like, How often does your physical health limit your ability to work? To maintain relationships? To enjoy the out-of-doors? Does your emotional health limit your social activities? Clergy scored considerably above the national average on the survey. That is, they perceived themselves as not limited by either physical or emotional health. When Proeschold-Bell first saw the results of this study she thought, “Maybe we don’t have a health problem among clergy.”

Then she looked at the physical tests that measured chronic disease and metabolic function. Those numbers told a different story. She found, for example, that 40 percent of UMC clergy in North Carolina were obese—a figure 11 percent higher than for the general population of North Carolinians and 14 percent higher than for the national population. The results were startlingly at odds with the perception of physical health in the previous measure. Clergy did not perceive the extent to which they had poor health.

Proeschold-Bell has two theories to explain the discrepancy. One is that the range of physical activity required for a pastor’s work is minimal, so clergy don’t perceive that they have a problem. “If all you have to do is get into your car, drive to the hospital, visit someone, get back in your car and then sit down and write a sermon, you may not be impeded by poor health.”

Her other theory is that clergy tend to spiritualize their approach to physical health: “If you feel spiritually well, that is a priority. You may not realize that spiritual health and physical health do not always coincide. You may think, ‘If I don’t get around to physical health because I am so busy with church work and that is living faithfully for me, then it’s OK.’”

The schedule of church work is clearly an impediment to clergy health. In every survey and conversation, the variable schedule and the demands of the vocation emerge as critical issues. Pastors do not have a nine-to-five workday; one day might look considerably different from the next—and eating is a major part of doing one’s job. Robin Swift, health programs director for CHI, said, “Clergy will say, ‘I would love to go on a diet, but I have three breakfast meetings this week alone.’”

If minsters perceive that they must choose between their own health and the health of their congregations, they will nearly always choose the latter, observed Proeschold-Bell. In part this is because of a phenomenon she calls (citing the research of Kenneth Pargament and Annette Mahoney) the “sanctification of work.” Clergy see their work not only as important but as divinely ordained. Whenever they act on behalf of their congregations, they are living in faithfulness to their vocations. When they leave work to go to the gym, they may see themselves as departing not just from a building but from doing God’s work. This is not an easy problem to overcome. Health behaviors don’t always have a ready-made theological justification. And the sanctification of work means that work will nearly always take priority.

Another factor contributing to a health crisis among clergy is the problem of agency. Self-determination is impeded on several levels. On a spiritual level, clergy have placed—or at least tried to place—the direction for their lives in the hands of God. For United Methodist clergy, this act extends to giving the denomination a great deal of say over where and in what congregations they will serve. Clergy’s daily schedules are often set by life’s demands and not by any ordinary schedule. Decisions about what and how much to eat or when to exercise often seem outside a minister’s control. Choosing when in the day to exercise and when during the year to go on vacation are not simple decisions. They often involve negotiations with staff, family and congregation. Each decision to eat well or to take time to exercise can feel like a decision to compromise one’s vocational commitments.

Ed Moore, theological education director for the CHI, recalls a discussion of the high rates of stress and depression among clergy in which a minister said, “Why do you assume that depression is not a natural response to the conditions of our lives?” This particular pastor was not complaining; he was pointing to the reality that the clergy vocation itself plays a major role in the health and well-being of pastors. Ordinary measures do not necessarily apply.

Because of the many unique characteristics of pastors’ situations, the CHI is designed to grapple with health in a holistic way. To address only the physical aspect of health would leave pastors simply feeling guilty about one more unmet demand. By addressing spiritual as well as physical health, by talking about stress as well as nutrition, the program tries to use pastors’ experiences as the starting place for change.

Moore, who oversees the retreat that begins the two-year program, draws extensively on Methodist tradition, making use of John Wesley’s own emphasis on physical health and the physical nature of God’s love. The CHI’s leaders believe that discussing physical health as a part of the work of sanctification is a way to connect to pastors’ self-understanding.

The Spirited Life program involves a nutritional component called Naturally Slim, a stress management program developed specifically for clergy, and regular contact with a wellness advocate, who is a cross between a coach and a personal assistant. During monthly phone conversations, wellness advocates might help a pastor research local gyms or exercise equipment or look up local doctors or search for vacation rentals. They may ask questions that pastors have specifically requested them to ask, such as, “Have you had any fun this month?” or “How is your exercise program going?” While they are listening, they are also taking notes for Proeschold-Bell’s research database which records the nature of clergy’s particular concerns. Wellness advocates are trained specifically for this work. Swift said that interpersonal and communication skills weighed far more heavily in the team’s decisions about whom to hire than any professional background.

Wellness advocates are careful not to set goals for pastors, since the CHI believes that the motivation for changing behavior must come from the pastor. Wellness advocate Tommy Grimm said that he finds this process delicate. “I don’t want them to feel that I am probing or pushing in any direction. There is no formula for this.”

When pastors ask Grimm to hold them accountable for some action that they have determined will lead to better health, he is reluctant to do it. “I don’t want pastors to feel like I am policing them. A pastor might say, ‘Can you hold me accountable to walking every day between now and our next phone call?’ I might respond, ‘That’s great. I will do that. But please know that if you don’t walk one step, I will not be angry.’”

Wellness advocate Kelli Christianson described a pastor who came into Spirited Life while already on a weight loss program. He joined the mindful eating program, lost 70 pounds and found the entire experience life changing. Christianson’s “motivational interviewing” has involved checking in with the pastor and helping him addresss various obstacles to a change he was already committed to making. “It is a huge success, and it will show up well in our statistics,” she said of the pastor’s progress.

On the other hand, she has also worked with a pastor who was far less clear about what the program had to offer and what she aimed to do with it. “It has been a long process to get her to even talk about what health looks like for her,” Christianson said. “It took 18 months for this pastor to begin to say things like, ‘I’ve been thinking that I would like to get out and start walking.’” While this particular pastor has lost no weight and won’t show up as a positive statistic, Christianson still perceived progress. “She has moved leaps and bounds in terms of readiness.” Not all change can be weighed on a scale.

The role of wellness advocate has been critical for Jeff Sweeney, an elder in the Western Carolina conference. When he signed on for the CHI he weighed nearly 300 pounds. His knees, back and ankles ached. He was on track for a heart attack or stroke. And his struggle was not simply physical. He was exhausted and burned out in ministry and in life. Having someone to check in with and set goals was critical. But the relationship with the wellness advocate required careful negotiations, and it took time for the two to learn how to talk to each other honestly.

The CHI is designed only to influence individual decisions made by pastors in their particular circumstances. Yet no one who has carefully studied the problem of clergy health believes that the problem is only or even primarily an individual one. Clergy are responding to cultural, denominational and congregational forces that are largely beyond their control. “We began to appreciate that there is an ecology to everyone’s health,” said Swift. Advocate Angela MacDonald noted that many spheres have to be adjusted if clergy health is to improve. “But as humans, we are very limited. Our abilities end at some point, and we have to trust God to provide the increase.”

Proeschold-Bell said that data from the group that is finishing the two-year program show excellent trends—substantial weight loss and improved scores in four of the five metabolic measures: waist circumference, blood pressure, triglyceride levels and hemoglobin levels (a diabetes indicator). What they have not seen is a decrease in levels of stress. This suggests that stress is a systemic problem that CHI is not equipped to address.

If she could make one cultural change with a wave of her wand, Proeschold-Bell would “shift the way that congregants think about their pastor. I would want them to think about the pastor as a whole person. Not as a person on a pedestal dedicated to serving them, but as a human being with flaws and graces, and as a person who has a life that needs fulfillment. I would want them to see that the pastor is a person they are going to have to partner with to create the kind of religious community they want.”