Our Mormon neighbors

The fact that the Constitution bars a religious test for public office does not, of course, bar citizens from taking religion into account when they vote. However, the spirit of the Constitution—not to mention political wisdom and the spirit of Christian charity—calls us not to vote out of blind prejudice for or against someone’s religion.

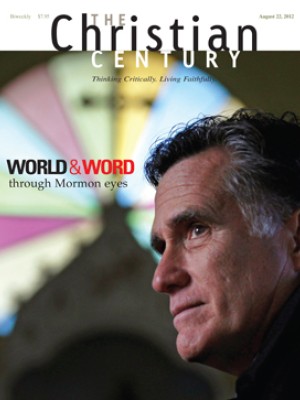

This year’s presidential contenders represent two religious traditions from outside the mainstream. Mitt Romney is a Mormon and Barack Obama is an adult convert to a liberationist strand of Afrocentric Christianity. Both traditions are distinctly American, yet they are little known, frequently misunderstood and sometimes vilified.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Unfortunately, political campaigns are rarely the occasion to increase the level of popular understanding about such matters. Candidates hesitate to reveal anything particular about their religious attachments, for they fear (with good reason) that such comments would only provide more fodder for partisan attack or ridicule (cue images of African-American pastor Jeremiah Wright pounding the pulpit or references to Mormon polygamy and magic underwear).

The rest of us need not forfeit the opportunity to learn at a deeper level. This issue of the Century aims to shed light on Mormonism. Though that faith has ranged far beyond Utah and become the fourth-largest religious body in the nation, and though it has lately been the subject of considerable media attention, the faith of our Mormon neighbors remains confusing and shadowy for most Christians.

Kathleen Flake ("The Bible plus") outlines one of Mormonism’s most distinctive features: its reliance on a revelation that supersedes (while it incorporates) the Old and New Testaments. The narratives of the Book of Mormon and the Pearl of Great Price form the basis for Mormonism’s unique story of human origins and of human salvation. These stories also lead to Mormonism’s departure from traditional Christian doctrine on issues such as creation and sin. Like other movements that arose in the 19th century in reaction to New England Calvinism, Mormonism stresses the importance of individual choice and takes an optimistic view of human possibilities.

Patrick Q. Mason ("Visions of Zion") describes how Mormonism started with a communitarian ideal and aimed to create a godly kingdom—another characteristically American aspiration. Over time, Mormons’ emphasis shifted away from community toward individual moral purity, though they retain a strong commitment to taking care of fellow believers in need.

Flake and Mason reveal a Mormonism that is thick with its own traditions of interpretation. There is not one way of being Mormon—politically or theologically—any more than there is one way of being Presbyterian, Pentecostal or Roman Catholic. Nor can one trace any one political stance of Romney’s to a distinctly Mormon belief system. Yet knowing the general features of the Mormon ethos does help one situate a figure like Mitt Romney and better understand this significant group of Americans.