Undressing another person, or another person's body, is a slow and exquisite work. Whether it's a feeble parent who can't manage the buttons, a child for its bath or an expectant lover, undressing can be an act of love. When a Jew dies, a small group known as chevra kadisha prepares the body for burial. First the body is reverently undressed, and any wounds on it are carefully cleansed. Rings, bracelets and all jewelry are removed. The body is bathed and purified by water, then wrapped in a white sheet and perhaps a prayer cloth and tied with a sash secured by a sacred symbol. Now it is ready to meet the living God.

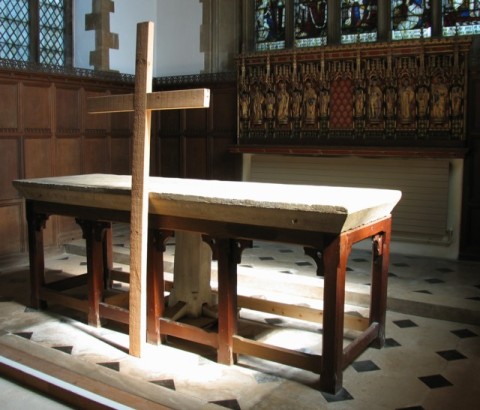

Each Maundy Thursday, the members of our church's altar guild carefully and lovingly remove the candelabra, cross, vessels, fine linens and paraments from the altar. They strip the altar to bare stone. When everything is removed, what is left is nude and vulnerable, not as imposing as one might expect. It seems almost a shame to see the altar that way, and so when the women are finished undressing it someone turns out the lights, and the congregation files out in silence.

Every time I participate in such a service, I think of Jesus, who on the night of his betrayal laid aside his woven tunic and tied a towel around his waist. He stripped for service. Another Gospel tells us that later "they stripped him" for mockery and death. The altar stands for Jesus, who in Holy Week enters the last stages of his ritual purification. The altar also stands for those from whom something or someone is being taken away. It stands for us. A sentence from one of Bonhoeffer's prison letters comes to mind: "I think that even in this place we ought to live as if we had no wishes and no future, and just be our true selves."