Is ‘compassionate conservatism’ obsolete?

The GOP primary candidates competing for the affections of Republican

voters have plenty of labels with which to tar each other: Influence

peddler. Failed politician. Cayman Islands account holder. Aspiring

polygamist. But perhaps the worst smear they could lob at an opponent

would be to call him a "compassionate conservative."

There's no

place for compassion in this race, which has featured debate audiences

cheering the death penalty and booing the Golden Rule.

Candidates

have jostled to take the hardest line in opposing government-funded

programs to help the poor, with Newt Gingrich calling Barack Obama a

"food stamp president" and Rick Perry blasting "this big-government

binge [that] began under the administration of George W. Bush."

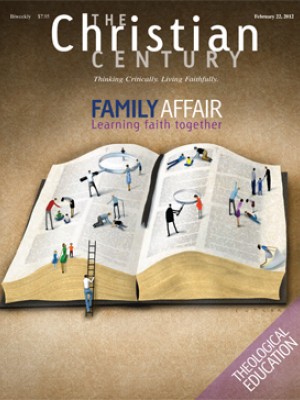

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Just

three years after Bush left the White House, compassionate

conservatives are an endangered species. In the new Tea Party era,

they've all but disappeared from Congress, and their philosophy is

reviled within the GOP as big-government conservatism.

Is this

just a case of the Republican Party wanting to distance itself from the

Bush years—or is compassionate conservatism gone for good?

Bush

was not the first person to use the phrase "compassionate conservative,"

but his adoption of the label in the 2000 campaign made it instantly

famous. Bush and his advisers sought to soften the GOP's image, which

had taken a beating during the years of Gingrich's speakership and the

Clinton impeachment. Bush's faith-based initiative was the signature

policy to grow out of his compassionate conservative philosophy.

In

2008, former Arkansas governor Mike Huckabee also ran for the GOP

nomination as a compassionate conservative, refusing to apologize for

supporting state tuition breaks for the children of illegal immigrants:

"You don't punish a child because a parent committed a crime." Huckabee

was fond of saying that he was a conservative, just not angry about it.

Like

the Ecuadoran horned tree frog, a handful of compassionate

conservatives can still be found—if you know where to look. Sen. Dan

Coats (R., Ind.), who was involved with faith-based initiatives before

Bush ever heard about them, is one. And former Bush aide Michael Gerson

continues to preach the gospel from his perch as a Washington Post columnist.

After the Iowa caucuses, both Gerson and New York Times

columnist David Brooks hailed former senator Rick Santorum as the

second coming of compassionate conservatism. And it's true that in his

victory speech in Iowa, Santorum sounded very much like a populist,

arguing that Republicans need to offer more than tax cuts and balanced

budgets to Americans who are struggling.

But when it comes to

specifics, there aren't many government policies—particularly domestic

programs—that Santorum supports to help alleviate poverty. He cheered

most of the harsh cuts in hunger and housing programs that House

Republicans proposed last summer. Santorum, a devout Catholic, has said

he believes that the U.S. Catholic bishops are wrong to back immigration

reform, and he has confessed that he is unfamiliar with the phrase "a

preferential option for the poor," which is an essential component of

Catholic social teaching.

There is a meanness to the way many

Republicans talk about the poor these days that was not in vogue during

the Bush years. Unlike Huckabee, they are angry conservatives.

Gingrich

spits out the words "food stamps" and implies that they are gold coins

showered on undeserving recipients. When debate moderator Juan Williams

asked Gingrich whether his comments are "intended to belittle the poor

and racial minorities," he was roundly booed by the conservative

audience in South Carolina.

The conservative Heritage Foundation

released a report in September arguing that those living under the

poverty line in the U.S. aren't really poor because they have

refrigerators and microwaves.

What happened to compassion? One

answer is that it turned out to be expensive. Providing housing and food

assistance, giving grants to charities that help low-income Americans,

supporting job training programs—these all cost money. The federal

deficit ballooned during the Bush administration, and though much of

that came from funding the Iraq War and an expensive Medicare

prescription drug benefit, Bush's domestic faith-based programs and

tripling of U.S. aid to Africa have been tagged with the blame.

In

addition, the Tea Party movement has embraced what political writer

Jill Lawrence calls "Darwinian conservatism." You could also call it

"Ayn Rand conservatism," after the libertarian philosopher whose work

many congressional Republicans praise. In 2010, Republican Senate

candidates attacked programs such as Social Security, student loans and

unemployment benefits, saying they made Americans lazy.

The

debates in this election cycle have also encouraged the turn away from

compassionate conservatism. Led by Gingrich, the candidates have played

to audiences hungry for red meat. These party faithful lustily cheer

attacks and boasts, and they boo any statement that carries a whiff of

moderation.

Just before the South Carolina primary, a progressive

Christian group called the American Values Network released an animated

video, Tea Party Jesus, to mock the disconnect between popular

conservative rhetoric and Gospel teachings. In a "Sermon on the Mall," a

cartoon Jesus stands flanked by GOP politicians and pundits as he

declares, "Blessed are the mean in spirit . . . blessed are the pure in

ideology."

It didn't take long for a Tea Party site to promote

the video instead of taking offense. Tea Party activists might not have

gotten the joke, but if the Republican Party rejects completely the idea

of compassion for struggling Americans, it will be no laughing matter.

—USA Today